In 1960, Jerome Stein, associate professor of economics, took his 7-year-old son Seth to hear a talk about continental drift by geologist Donald Eckelmann, also a dean at Brown at the time. Seth demonstrated his early aptitude for geology by jumping up when Eckelmann asked for questions.

"He said, 'You mean it's like bars of Ivory soap in the bathtub?'" Jerome recalled. "This was the beginning of the earth science continental drift, sea

floor spreading, which was very new. So he was in at the beginning. ... No one had ever heard of these things before."

Seth went on to study geology at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology.

"It was the best time for geology ever," Seth said, calling the 1960s "the decade of geology." Moon landings and the entrance of plate tectonics into the field made it particularly exciting, he said. Today, he teaches in the Department of Earth and Planetary Sciences at Northwestern University.

Jerome has remained at Brown, where he is currently a professor emeritus of economics and a visiting professor in the Division of Applied Mathematics.

Over the years, Seth and Jerome read each other's work and inevitably discussed science at family functions, Seth said. But it wasn't until the past year and a half that they officially teamed up for the first time.

Seth had written a paper on the Tohoku earthquake and tsunami of March 2011, and Jerome had published a book on the 2008 financial crisis. Seth said they were comparing notes when they realized that the events had certain similarities.

"We decided we should look at these together in an integrated sort of way," he said.

One paper, "Gray swans: comparison of natural and ï¬nancial hazard assessment and mitigation," was published in September in the journal Natural Hazards. The paper compares these two disasters, saying that the devastating impacts of both the Tohoku earthquake and the U.S. financial crisis "resulted from unrecognized or underappreciated weaknesses in hazard assessment and mitigation policies."

A second paper, "Rebuilding Tohoku: A joint geophysical and economic framework for hazard mitigation," was published last month in GSA Today, the news magazine of the Geological Society of America. The article examines how the effects of natural disasters can be most effectively mitigated at the lowest cost.

"Usually, these decisions are made very politically," Seth said. "So usually the decisions aren't very good."

Jerome said the U.S. Geological Survey in particular has a vested interest in generating fear of natural hazards and has even gone so far as using "scare tactics" to convince people that extreme preventive measures were necessary, even when the actual threat was relatively small. Their policy was always, "There's no limit to what you can spend. You can't be too safe," Jerome said.

Actually, the Steins say, you can.

The resources that would be spent producing ineffective mitigation could be used for better purposes, Jerome said, and some mitigation methods might even be counterproductive. Seth noted that the Tohoku tsunami killed a large number of people who did not evacuate because they assumed the sea walls would keep them safe.

"The question is not what is good or nice, but how much is enough," Jerome said. "How much is enough. Those four words are everything."

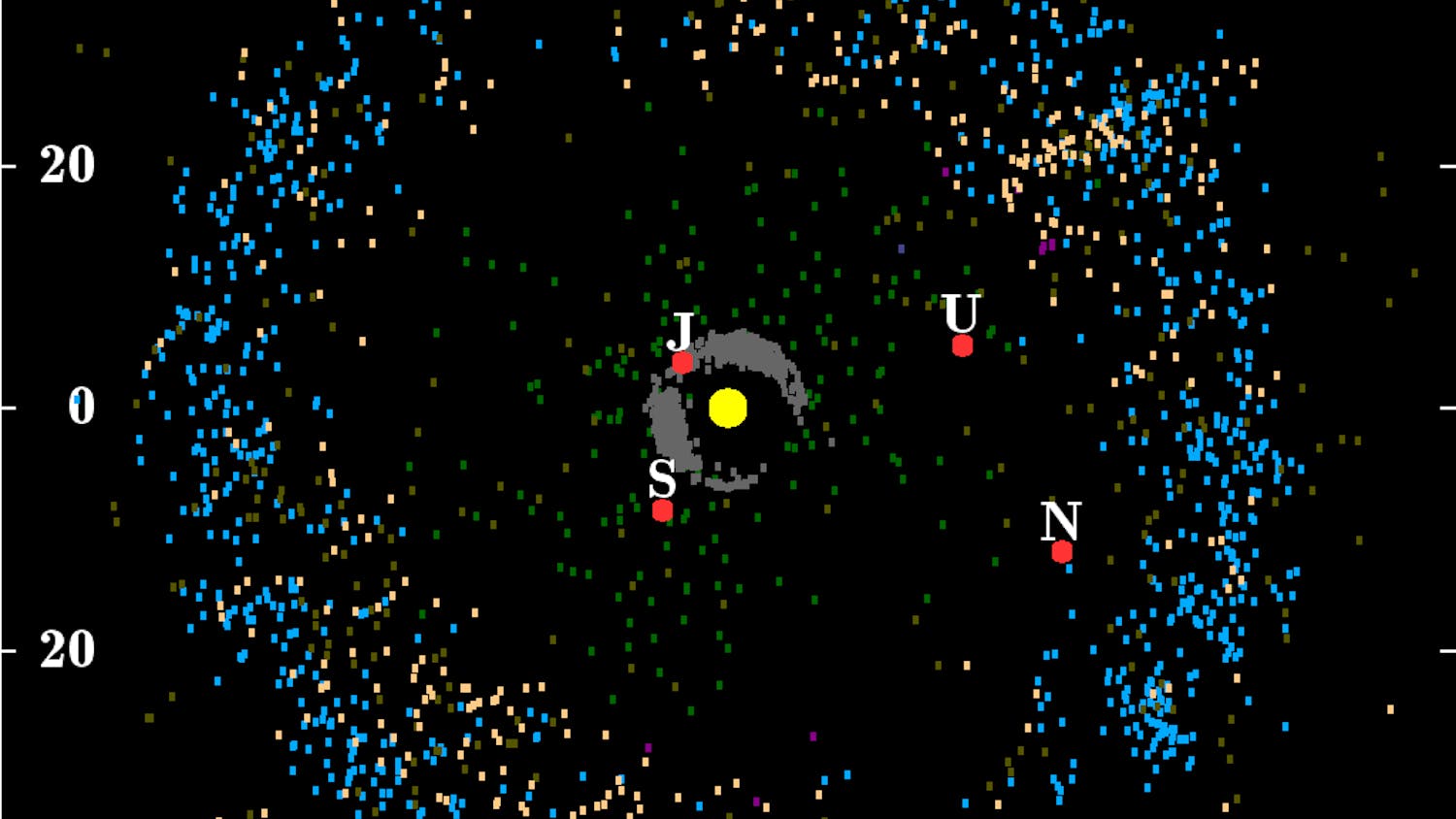

Their model begins with a given natural hazard, such as a tsumani, and the level of mitigation implemented to combat it such as a seawall. It factors in the severity of the hazard, such as the height of the tsunami and the extent of the mitigation such as the height of the seawall. The model also incorporates the probability of such an event to find the expected loss "over the life of the wall."

The sum of the expected loss is then added to the cost of mitigation to find the total cost. Graphing the total cost produces a U-shaped curve with its minimum at the optimum level of mitigation.

The Steins also accounted for the high uncertainty in predicting natural hazards, as well as risk aversion, or the tendency to over-prepare because of the high stakes involved. These two factors shift the minimum toward greater mitigation.

"I did the mathematics and economic modeling, and (Seth) then changed it in a way that could be understood by the geological audience," Jerome said. He said this "interactive process" took place mostly over email, with Seth making periodic trips back to Providence. "There's a lot to be said for face-to-face," Seth said.

"The biggest challenge for us in collaboration was understanding each other's language," Jerome said. He said though they sometimes disagreed on how to best approach a problem, and though Seth could be "strong-minded" at times, their family relationship had a positive effect on the process.

"He knows my skills," he said. "No one in the geological community would have that knowledge." Jerome added that "there's not an invidious distinction on authorship."

Seth said combining their two fields helped them gain "a lot of insights you wouldn't get from one" and also allowed them to present their findings to both mathematicians and geologists.

Though the study's methods were foreign to most geologists, who were not accustomed to thinking about natural hazards in terms of cost-benefit analysis, its reception was generally positive, and the Steins are optimistic about the impact it may have on policymaking in the future, Jerome said.

"I think there's a rising awareness of the need to do cost-benefit analyses for natural hazards," Seth said.

A third paper, "Formulating Natural Hazard Policies Under Uncertainty," has been submitted for publication.

Their next target? Global warming and climate change. The father-son duo is currently working on a book, "Playing against nature: integrating earth science and economics for cost-effective natural hazard mitigation," which will apply economic models to problems facing the environment.

ADVERTISEMENT