Like T.S. Eliot’s poem “The Love Song of J. Alfred Prufrock,” Carson Kreitzer’s play “The Love Song of J. Robert Oppenheimer” is preoccupied with the human capacity for harm.

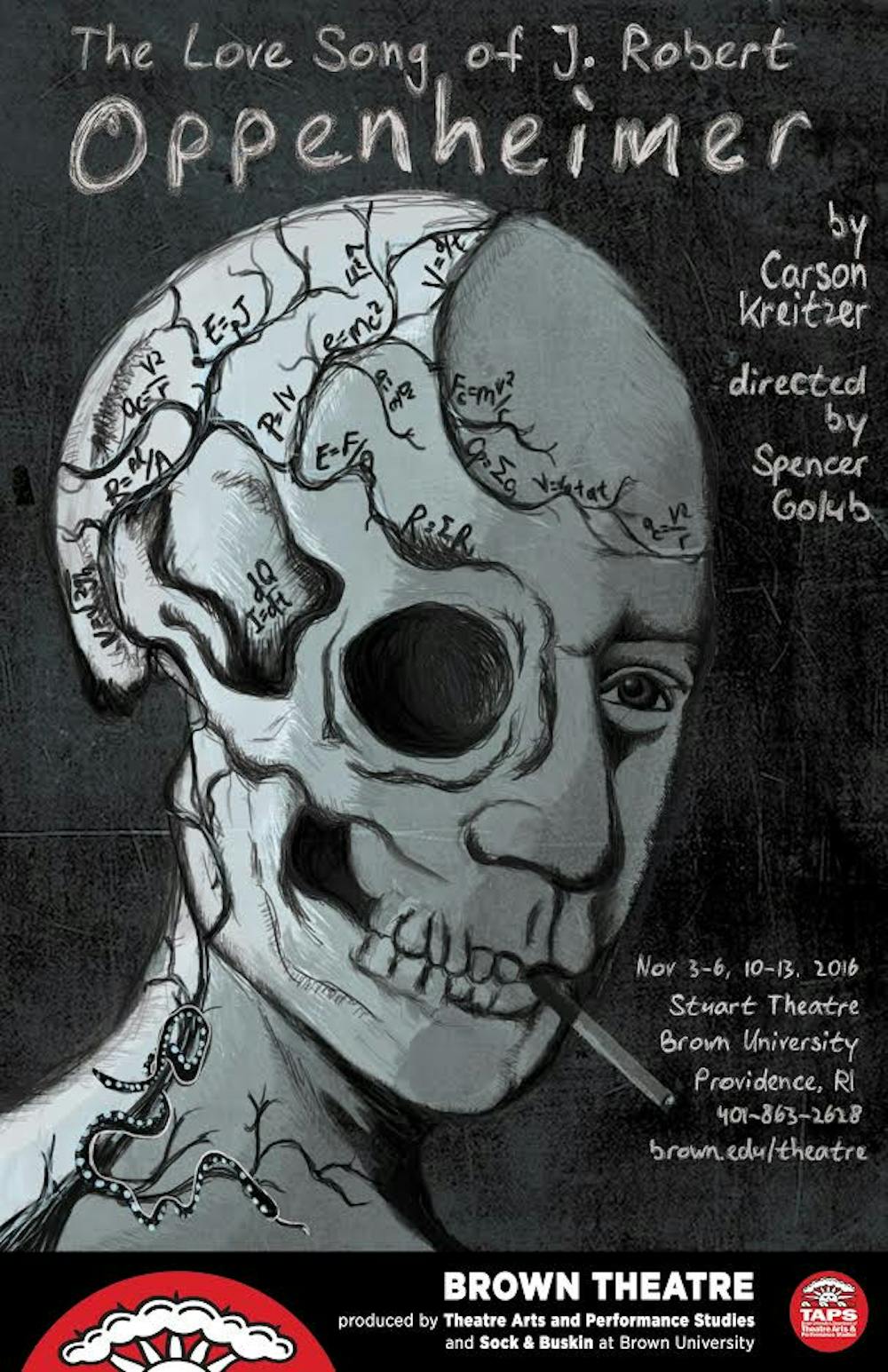

The Sock and Buskin production ran Nov. 3 to 6 in the Stuart Theatre and will be running again Nov. 10 to 13 as advertised on the play’s evocative poster featuring an x-ray of the eponymous Oppenheimer’s skull. Featuring physics equations scribbled across Oppenheimer’s brain and a lit cigarette askew in his mouth, the poster is a testament to the theoretical physicist’s place at the volatile boundary separating beauty from devastation in knowledge.

The play examines the life of one of the 20th century’s most profound and tortured scientific minds. Oppenheimer — who spearheaded the research backing the Manhattan Project, which led to the creation of the atom bomb — spent the latter half of his life making sense of the ruination that his research unleashed on the world.

“Do I dare / disturb the universe?” Prufrock implores in Eliot’s famous “Love Song.” This sentiment is accordingly echoed throughout much of Oppenheimer’s moral struggle — a disquietude singularly conveyed by Jason Roth ’17. Oppenheimer, after upending the lives of hundreds of thousands of Japanese civilians, comes to invoke the Bhagavad Gita’s Krishna, labeling himself “Death, the destroyer of worlds.”

Rife with these kinds of textual allusions, the play almost functions as an analogue to Eliot’s poetry. With its deeply layered and literary portrayal of Oppenheimer, the work accords a due amount of nuance to the scientist’s life. Oppenheimer’s “love song” manifests itself through various conduits, from poignant portrayals of his grief to melodrama involving his suicidal lover to erratic evocations of the poetry of John Donne. The play encapsulates the same side-winding modernist conventions that made such poems as Eliot’s “The Wasteland” seminal parts of the Western canon and establishes Oppenheimer as a humanist at heart.

“That was his huge problem as a scientist,” said Director and Theatre Arts and Performance Studies Professor Spencer Golub. “He was too caught up in the beauty of everything.”

The theoretical physicist was passionate about French and Sanskrit poetry, works of art for which “there was no patent,” as a character points out in the play.

Golub brought new life to the interpretation of the physicist’s life. “I didn’t know anything about the play,” Golub said. “But I was, perhaps coincidentally, thinking about Oppenheimer, Judaism and the atomic bomb — all the bases this play touches on — when students brought it to my attention.”

Sock and Buskin chose the play with the intention of prompting dialogue on diversity and inclusion in light of recent campus conversations on the matter.

Leonard Cohen’s “Famous Blue Raincoat” serves as the play’s desolate refrain, soundtracking much of Oppenheimer’s romantic and existential distress. But the song, written by a musician and poet well-versed in the Judaic tradition, also speaks to issues of identity tackled in the play. Oppenheimer points out that he did not ask for the fame the Manhattan Project brought him. Rather, Jews were relegated to the then-impractical field of theoretical physics because of their identity. The physicist’s struggle to reconcile his Jewish identity with his work was what Golub calls “the most problematic part of Oppenheimer’s life.”

Oppenheimer was far from an observant Jew, tending to look toward Sanskrit rather than the Talmud in his trials and tribulations. The play underscores this muddled sense of identity and attributes it to the anti-Semitism Oppenheimer faced as a theoretical physicist, a largely Jewish occupation. Oppenheimer may have been one of the esteemed Los Alamos scientists, but to echo his lover, many saw him as little more than just one of “a bunch of Jews in the desert arguing esoteric points.”

“You’re living for nothing now,” Cohen croons. With the curtain pulled back on humanity’s fractured psyche, Oppenheimer is struck by existential paralysis and a sense of alienation that enables “The Love Song of J. Robert Oppenheimer” to build on the greater modernist tradition. After Hiroshima, as another scientist shares with Oppenheimer, the physics is “not theoretical anymore.”