Khaled Almilaji GS, whose U.S. visa was revoked while traveling to Turkey over winter break, is building the Avicenna Women and Children’s Hospital in Idlib City, Syria with his organization, the Sustainable International Medical Relief Organization. Health facilities in Idlib City and the larger Idlib Governate, which is controlled by the opposition forces, are routinely attacked by government forces, and the city is less than 40 miles from the site of the April 4 chemical attack, Almilaji said over Whatsapp from Gaziantep, Turkey. There is a severe lack of services for women and children in the area, he added.

As Almilaji is working on running the project, he is trying to get a visa to return to Providence to continue his Master’s in Public Health and reunite with his pregnant wife, Jehan Mouhsen, who is due with their child in August. He is also working with colleagues at the University to develop services and raise funds for the hospital.

Building underground

The government frequently attacks health facilities, Almilaji said. The structure where he is building a new hospital — formerly a hospital itself — has been repeatedly attacked, he added.

SIMRO, which is also known as the Canadian International Medical Relief Organization, is building on the two basement floors of the structure. Building underground makes the facility 70 to 80 percent more secure from missile attacks and barrel bombs than above-ground hospitals, Almilaji said.

Most patients “prefer not to go to health facilities or to spend the minimum time in any health facility because everybody knows by now that those … are the most targeted facilities in the whole war,” Almilaji said.

Being underground will also allow them to provide surgical care absent in above-ground hospitals because “doctors are not willing to sit there for five to six hours because it’s so dangerous,” said Melissa Godfrey MPH, a classmate of Almilaji who is also helping him to fundraise for the hospital and create a media campaign. The basement location “will increase the ability to provide care to patients.”

But “almost no facility can handle the Russians’ attacks. … There is no place secure inside Syria,” Almilaji said. The United Nations Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs, a funder of the hospital, has offered to share the coordinates of the hospital with Russia in an attempt to have it spared from bombing.

Developing needed services

“We have to keep delivering services, at least to the most vulnerable groups, which are women and kids,” Almilaji said. Most of the remaining medical services available in Idlib deal with trauma, and specialized services for children and women are scarce. The hospital will “host a whole women and children’s facility, a whole medicine department and an emergency and trauma department,” Almilaji added.

Almilaji, who is a Humanitarian Innovation Initiative International Fellow at the Watson Institute for International and Public Affairs, has asked for support from the Humanitarian Innovation Initiative, said Adam Levine, director of HI2 and associate professor of emergency medicine. HI2 plans to work with the hospital on a telehealth project.

“Most specialists and doctors and nurses have left the country, so there’s really only small numbers of trained individuals who are available to staff this hospital, and many of them have a generalist experience and not necessarily specific skills in (areas) like critical care, maternal health or child health,” Levine said. “Through a telehealth program, we would organize trainings for staff at this hospital in Idlib” and others in the region, he added.

Almilaji is still figuring out what areas of support from HI2 will best help the hospital. Telehealth services range from videoconferencing that would allow specialists in the United States to train doctors in Idlib to messaging services that would allow doctors in Idlib to consult with U.S. partners on specific cases in real time.

“Likely we would recruit a cadre of volunteers: physicians, specialists in different areas — preferably ones (who) speak Arabic (and) have experience working in these kinds of settings. It will probably be a large roster because it will have to cover all sorts of different specialties,” Levine said. “I don’t think we’ll have a hard time finding” volunteers, he added.

HI2 plans to work with the Alpert Medical School, the School of Public Health and specialists to develop this partnership. They will also look to the Nelson Center for Entrepreneurship to help reach out to the tech industry, Levine said.

“What I love about this project is it’s not about humanitarian aid workers from Brown or from the U.S. going to help people in need in Syria. It’s about building the capacity of local physicians and nurses to provide care for their own people in the midst of a crisis,” Levine said.

Funding the project

The hospital, which is 75 percent finished with renovations, is currently being funded by the UNOCHA and Expertise France. But it still needs $150,000 to finish rehabilitation and $600,000 for medical equipment, Godfrey said. The projected operational cost for a year is $1,200,000, and while it may receive operational support from the WHO in the future, the hospital needs private funding to start running, she added.

Godfrey is trying to start a mass media campaign in the United States, which she hopes will catch the eyes of large private donors. She also hopes that people will donate to the hospital through Refugee Protection International, SIMRO’s NGO partner.

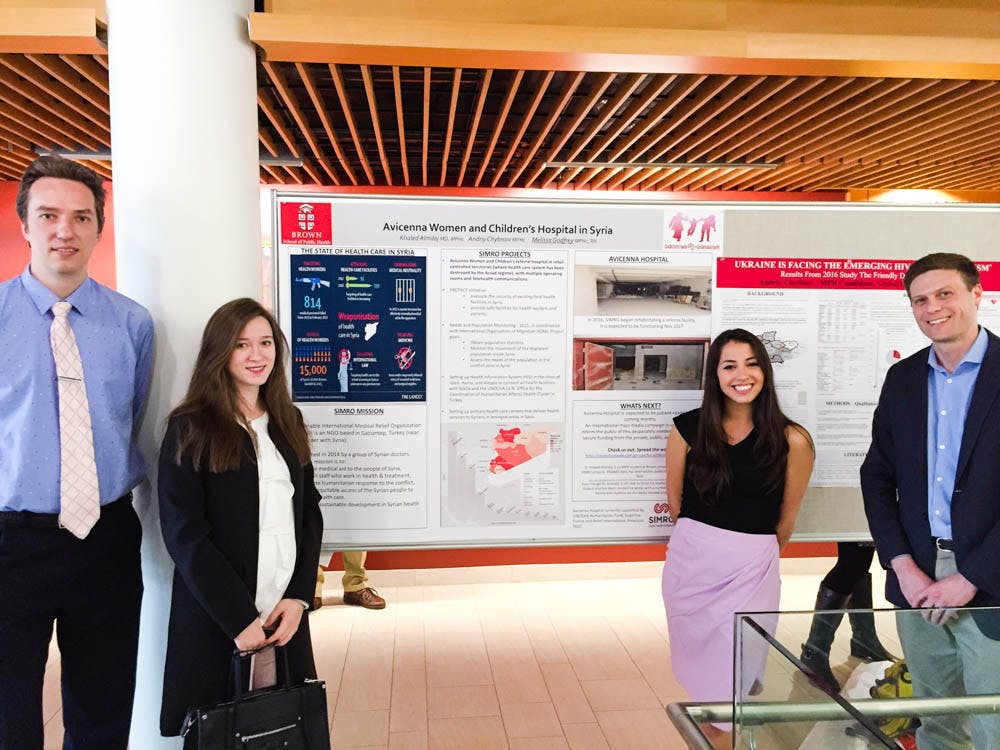

Godfrey and Mouhsen presented on the hospital at Global Health Research Day at the Med School Monday.

HI2 is given a small budget from the University, so it will try to raise money for its partnership with the hospital by applying for funding both within and outside of Brown. “It’s going to be a really big undertaking,” with “huge costs involved in setting up the whole health program,” Levine said. Additional costs will come from administration of the program, developing and hosting trainings and hiring real-time translators to assist participants in the United States and Syria who do not speak both Arabic and English.

Moving forward

Almilaji has been unable to come to the United States since his visa was revoked in January, and it has been three months since he has applied for a new one — with no word from the U.S. embassy. “Of course I’m trying to come back” to the United States, Almilaji said. Mouhsen is due with their child soon, and he does not want to further delay his studies. If he does not receive a U.S. visa soon, he and Mouhsen will reunite in Toronto, where he will study at University of Toronto’s Dalla Lana School of Public Health.

“I’m excited for a new opportunity,” Mouhsen said, although staying in the United States is also her first choice. What is most important is “being with my husband and getting back to a normal life. We’re newlyweds, we just spent a few months together (before) this all happened,” she added.

Mouhsen, who is also a doctor, was studying for the U.S. Medical Licensing exam — now, she is studying for the exam’s Canadian analogue.

The couple plans to return to Syria after the war stops, Mouhsen said. “We just need to get educated, so we can be more productive when we get back,” she added. Mouhsen wants to develop a specialty practice, which will be scarce in Syria; Almilaji wants to be prepared to help rebuild Syria’s health system.

In the past few months, Mouhsen has been alone and pregnant in a new country. This has been very difficult for her, she said, especially because she and Almilaji had barely been married before they were separated. The support of friends, as well as strangers who have sent her messages of support after reading about her in the news, has been helpful, she added. “I don’t want people to feel sorry for me.”

The “people are just wonderful” at Brown, and she appreciates the support from the University, Mouhsen said. “I have a wonderful impression of the whole country,” she added.

During her time in Providence, Mouhsen has made a lot of friends, and “I’ll feel sorry leaving them” if she moves to Canada, she added.