Following his outing last Friday against the Arizona Diamondbacks — a six-and-a-third-inning effort in which he surrendered four earned runs on four solo homers — Los Angeles Dodgers starting pitcher Clayton Kershaw is now 15 starts and 95 and-a-third innings into his playoff career. That’s about a half-season’s worth of pitching, a sample large enough to warrant entertaining the possibility that Kershaw’s pedestrian playoff performance might be due to something other than random variation.

Kershaw owns a 4.63 earned run average in the postseason, a mark nearly double his career regular season 2.36 ERA. While fewer than 100 innings aren’t sufficient for ERA to stabilize near a pitcher’s true talent level, consider this: Since the end of his rookie season in 2008, Kershaw has had just two halves of seasons — the first halves of 2011 and 2009 — where his ERA has risen above 3.00.

The main cause of Kershaw’s playoff struggles has been his propensity to give up the long ball. He’s allowed more than twice as many home runs per nine innings in October as in the regular season. This could be connected to his poor playoff strand rate, the percentage of batters who reach base that fail to score, which sits 15.1 percentage points below his career regular season rate. It is tempting to blame Kershaw’s inability to keep teams in the yard on his inflated home run per fly ball percentage, as balls lifted in the air against him in the postseason have left for home runs nearly twice as often than over the rest of his career. HR/FB percent is notoriously volatile, and it could very well be the case that Kershaw has simply been a victim of the randomness of baseball.

Still, there are real concerns to be had about Kershaw’s playoff mediocrity. Hitters have popped more balls into the air with more authority against Kershaw in the postseason: Per Baseball Savant, batters have recorded an average launch angle 7.1 degrees higher off him in the playoffs with an average exit velocity 3.7 mph faster. Those numbers go a long way toward explaining Kershaw’s playoff HR/9 numbers, but it’s unclear how much of the uptick in opposing batters’ quality of contact is noise and how much can be attributed to something unique about the postseason.

The issue doesn’t seem to be Kershaw wearing down late in the season, nor does it seem to stem from the amount of starts he has made on short rest in the playoffs. Kershaw’s average fastball velocity has actually risen .6 mph to an average of 94.4 mph in October, per Baseball Savant. And he’s pitched to the tune of a 3.15 ERA in the four starts he’s made on three days rest following a previous start — down a run and a half from his overall postseason ERA.

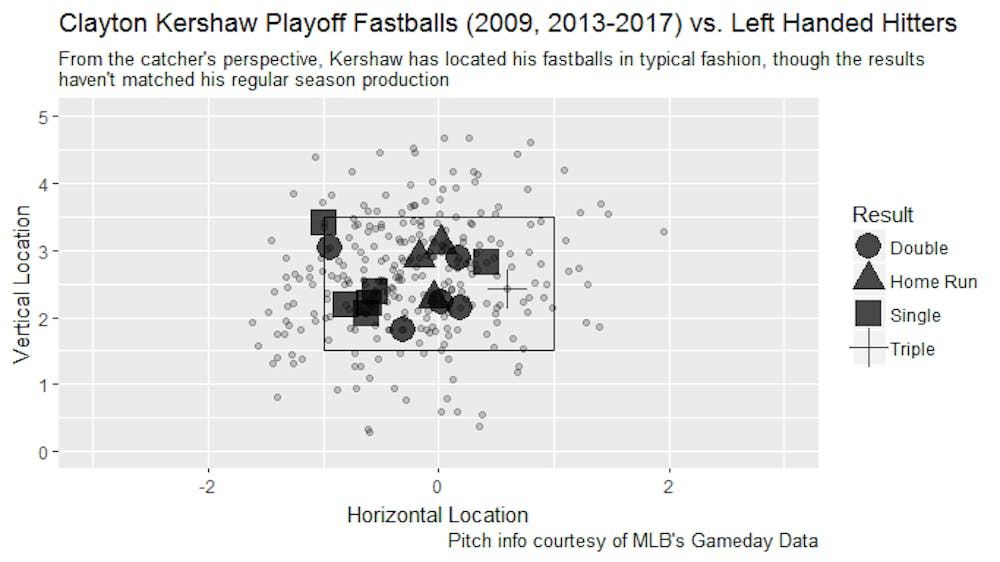

One area where Kershaw has faltered in October, though, is getting lefties out. Left-handed batters have posted a .243 weighted on-base average against Kershaw over his career during the regular season, but in the postseason, that number has spiked to .339, which is above the league average. Most of the damage has come off fastballs: Lefties are hitting .333 with a .704 slugging percentage against Kershaw’s four-seamer in the playoffs compared to just .219 and .380 in the regular season.

The fastballs left-handed hitters have punished Kershaw on generally weren’t well executed pitches — except for the two in the top left corner in the graphic, batters have simply taken advantage of Kershaw catching the middle of the plate. Yet comparing Kershaw’s regular season fastball location heatmap to his postseason heatmap on Brooks Baseball, there exists little discernible difference. Kershaw makes mistakes in the regular season, too, they’re just getting ripped more often come October.

Some of that might be dumb luck, but it appears that lefties have altered their approach against him in the playoffs. Over his regular season career, left-handed batters have swung at Kershaw fastballs located over the plate and in the middle horizontal third just 74.1 percent of the time, per data from Brooks Baseball. In the postseason, they’re offering at fastballs in that same location 85.96 percent of the time.

Kershaw has thrown too few playoff innings to make a definitive judgement about his effectiveness in October, and he’s certainly due for some regression to the mean in his home run prevention going forward. But if lefties really are, for whatever reason, making the conscious decision to jump on more of his fastballs in the playoffs, Kershaw may have to adapt if he wants to replicate his regular season success throughout the postseason.

The Dodgers are once again just four wins away from a National League pennant with game one of the National League Championship Series one day away. And given that the franchise’s current World Series championship drought dates back to 1988, the urgency is clear: Los Angeles needs their ace starting tomorrow.

A little batted ball luck wouldn’t hurt, either.

Sam Grigo ’18 is a Herald sports columnist and can be reached at samuel_grigo@brown.edu.