The United States’ position as the “defender of democracy” is a narrative that has always dominated the shaping of the American identity. We employ the rhetoric of a country founded by the people, for the people, which serves as a champion model for other countries to admire and imitate. While there are many reasons to be skeptical of this master narrative, there is one in particular that rises to the surface as we move into this electoral season — voting in America.

What does it mean to be the “defender of democracy”? It does not seem to mean having the most active democratic process, for the United States ranks 26th on the list of countries with the highest voter turnout. It definitely does not seem to mean respecting democracies abroad, as many in Latin America and the Middle East alike can testify to the gross injustices the United States has carried out in the name of democracy. Perhaps then it means, at the very least, a theoretical understanding and faith in the idea of democracy itself, for the country is said to have been built on those very values. However, a general disillusionment with the democratic process in the United States has plagued Americans in recent years, suggesting that our title as the “defender of democracy” has become, and potentially has always been, meaningless rhetoric.

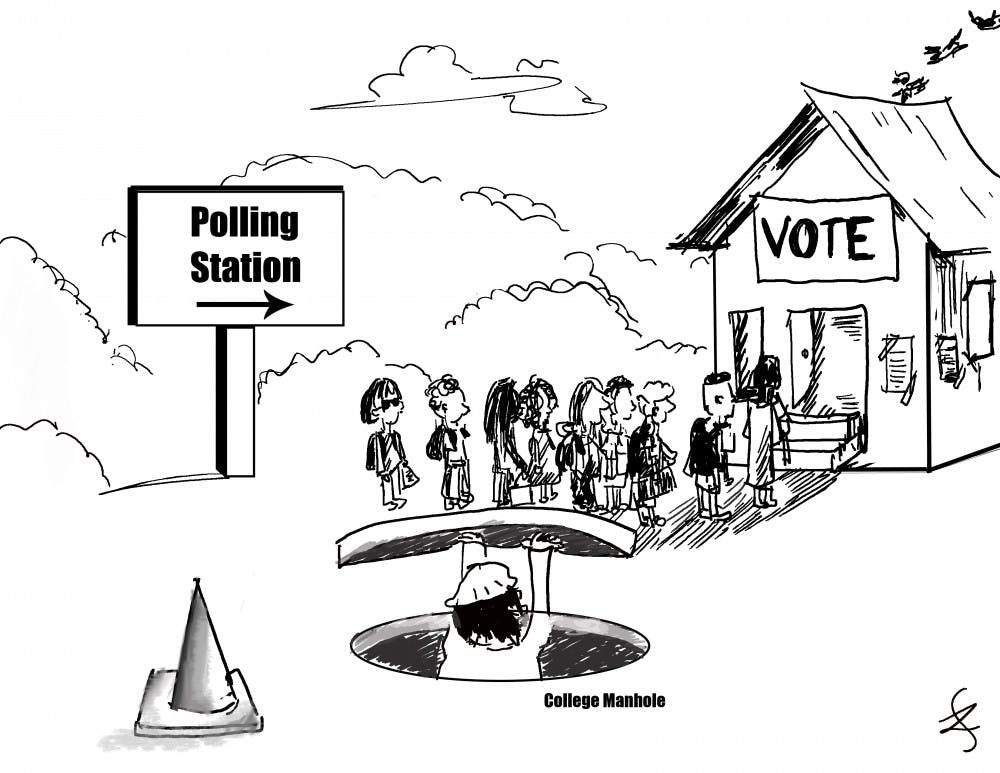

To rise to our democratic values, American citizens must vote in greater numbers. But even in the face of the crucial 2018 elections that have the power to shape the political landscape for years to come, many people are not expected to vote. Young people in particular, who often claim to be driving the social revolution that has supposedly been taking place in the 21st century, have the lowest voter turnout rates. The relevant question is whether democracy works if people, even the politically conscious who can vote, choose not to exercise it. I believe the answer is no. How then do we reclaim that vote?

There is a long list of changes that need to take place to re-legitimize the electoral system, namely the removing of big money and corporate interest from the process of choosing leadership. There is a growing suspicion, which I argue is not completely unwarranted, that we go through the motions of democracy to give off the appearance of representation, but the real decisions are made behind closed doors and are constructed to take place in a predetermined way. This sentiment has led to the development of the group of non-voting political activists, which I believe many young people fall into. This is the politically conscious person who refuses to participate in a system they believe to be fraudulent. While I can respect such intentions, the truth is that abstention is not political activism, but the ultimate form of consenting to the way the system currently runs. The more hopeful truth is that, while each vote might not hold the political capital it claims to possess, the vote still counts for something. If everyone were to vote, it would be much more difficult to justify ignoring the entire voting population in favor of special interests.

Voting, regardless of how legitimate you believe our democracy to be, and again I do not argue that it is at all a fair and equitable system, is a great responsibility of serious consequence. The issue grows in importance and interest when considering the educated youth in the country — for example, students at Brown. Choosing to vote in your home state, to vote in Rhode Island or to not vote at all comes with a whole other host of implications, as we come from a position of great privilege. We are quite self-congratulatory in our political education and our strong opinions. But what does it mean if we choose not to invoke that education and those opinions to remove ourselves from the bubble that is the space of the University, momentarily, and find solidarity with people off of College Hill? The role of the privileged, politically conscious person does not end with voting. I have always been and continue to be a strong advocate of action from outside of the established political structure, believing it to be inherently necessary in systems that are so blatantly corrupted and biased. However, I find it difficult to argue against the fact that voting, and not exclusively in the big elections, is an essential first step. It is a first step that can act as an immediately accessible tool for significant change, and at the very worst is potentially inconsequential. It seems clear that there is little to lose and too much at stake to abstain.

Marysol Fernandez ’21 can be reached at marysol_fernandez@brown.edu. Please send responses to this opinion to letters@browndailyherald.com and other op-eds to opinions@browndailyherald.com.