When it comes to introductory science courses, not all classes are created equal.

In introductory physical science courses, such as chemistry and physics, a much larger percentage of students reported taking the course to fill a requirement than did students in introductory life science courses like biology and neuroscience, according to data from the Critical Review.

The divide results from a variety of factors, students, faculty members and higher education experts said. These include the level of math the courses call for, laboratory section requirements and general student perception of the discipline’s difficulty and applicability outside of academia.

Who fills the seats of lecture halls for introductory courses also depends on who is behind the lectern. In choosing which faculty members will teach introductory courses, departments are keenly aware that some professors create a more captivating lecture atmosphere, while others work more effectively in smaller, higher-level courses. Students said reputations of professors who teach introductory courses could sway students from discipline to discipline.

Unpacking the divide

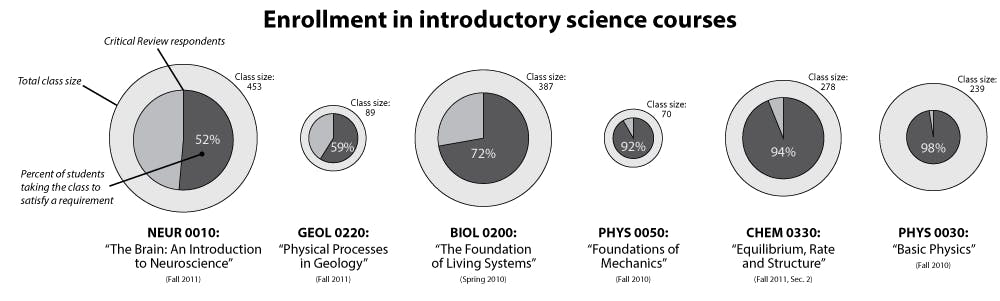

In the fall of 2011, 48 percent of students who responded to the Critical Review survey for NEUR 0010: “The Brain: An Introduction to Neuroscience” reported they were not taking the course to fulfill a requirement. The semester prior, nearly one quarter of Critical Review respondents in BIOL 0200: “Foundation of Living Systems” reported they took the course without satisfying a requirement.

But introductory courses in the chemistry and physics department are filled with students who report taking the course as a requirement. A mere 6 percent of students in one section of CHEM 0330: “Equilibrium, Rate and Structure” reported they were taking the course as an elective in fall 2011. Only 2 percent of students in PHYS 0030: “Basic Physics” in fall 2010 took the course as an elective, while only one student out of 114 survey respondents in PHYS 0040: “Basic Physics” in spring 2012 reported taking the class for a reason other than fulfilling a requirement.

Students looking to take an introductory science class for fun may avoid chemistry and physics classes due to the “premium on competitiveness” caused by the number of pre-medical students, said Mitchell Chang, a professor from the University of California at Los Angeles who studies higher education trends.

The predominance of pre-med students in PHYS 0030 means “there are very few students who take physics 30 for fun,” said James Valles, chair of the physics department and associate dean of the College for curriculum. “People who take our intro course because they are interested — they wind up in physics 70,” an alternative introductory course, he said.

In addition to the threat of student competition, prevailing student interest affects which courses draw crowds.

“Given student interests now, we are never going to have the numbers that neuro and bio have,” said Robert Pelcovits, professor of physics.

“Intro biology sounds more accessible than analytic mechanics,” said Will Stephenson ’15, who enrolled in PHYS 0500: “Advanced Classical Mechanics” with no intention of fulfilling a requirement and later decided to major in the field.

The divide between the life and physical sciences may also be attributed to a “conscious tailoring” of physical science courses, said Wesley Bernskoetter, assistant professor of chemistry, who taught CHEM 0330 in the fall.

Classical physics is an older field than neuroscience, so the material students must learn for physics has significant depth and breadth, he said. “It’s a bigger challenge to tailor a class of that nature to an audience of students simply looking for this as a for-interest only class.”

Matthew Zimmt, professor of chemistry and chair of the department, said introductory chemistry courses had similar objectives.

“There are very few … ‘one, fun and done’ courses in chemistry,” he said. “There are people who would like to have a course where they can just learn a little about something,” he said, but the objective of a course like CHEM 0330 is for students to both understand the basics of the subject and to see how those facts connect to the world.

Further disparity between student interest in the life sciences as opposed to in the physical sciences may be attributed to student perceptions of different fields.

“Something like neuro seems shiny and new,” said Richard Stratt, professor of chemistry, who has previously taught CHEM 0330. “(Students) don’t realize the parts of chemistry that are new and exciting.”

While chemistry and physics may sound archaic to students, biology is also more readily apparent in the world, Zimmt said. “You see birds, you see animals. … How many times have you stopped to look at something and thought about its chemicals?”

Professor of Biology Ken Miller ’70 P’02 said biology is key to understanding current issues.

“Look at how many political questions in the public sphere right now have biological content,” he said, citing climate change, energy, genetically-modified food and stem cell research. “These things are more easily dealt with if you know something about biology, so I think that’s part of the attraction,” he said.

Limits and logarithms

The quantitative aspect of the physical sciences may also deter students from taking introductory chemistry and physics courses.

“Perhaps the most important distinction between the life sciences and the physical sciences at the intro level is the level of quantitative expectation,” said Katherine Bergeron, dean of the College. “How much math has to be in hand to begin to address the fundamental questions and to do hands-on research?”

Students who enroll in physics without a solid math background find themselves “struggling to learn two things” at once, Stephenson said.

The math requirements of introductory chemistry, physics and engineering present a challenge for professors and students alike. Stratt said the “heterogeneous” nature of students’ math and chemistry backgrounds was the biggest challenge he faced teaching CHEM 0330.

“It’s hard to constantly be in such a one-room schoolhouse,” he said.

Stephenson said much of the material of CHEM 0330 overlapped with his high school Advanced Placement Chemistry class. “People who haven’t taken AP get screwed,” he said. “It’s either too easy or too hard. There is no middle ground.”

The engineering department recognizes the math in introductory courses will be easier for some students but hopes design projects and the necessity of teamwork will help level the playing field, said Kenneth Breuer, professor of engineering.

“There is a lot of effort to help the students who need to catch up … that brings most people to more or less the same level” by the end of their first semester, he said.

Clocking lab time

Labs may also deter students from taking introductory science courses, students and faculty members said.

While making introductory science courses lab-optional might encourage more students to enroll, losing the lab experience is not worth attracting more students, Stephenson said.

“There is a general perception that labs are hard,” Miller said. With additional time requirements but not extra course credit for laboratory courses, “an intensive laboratory course never seems like the easy way out.”

But if designed well, a laboratory component to a course actually has the potential to increase student interest in the subject, said John Stein PhD’95 P’13, senior lecturer in neuroscience. Faculty members constantly redesign labs to best engage students, striking a balance between “cookbook labs” in which students achieve predictable yet reliable results and “open inquiry labs,” which lend more insight into actual scientific discovery but are difficult to execute with large classes, he said.

“To really understand science, you have to get your hands wet,” Miller said.

All about the reputation

A pivotal factor influencing whether students enroll in introductory courses is instructor reputation, students said.

The introductory biology and neuroscience professors have extraordinary reputations, said Zack Winoker ’13. “There is a well-justified culture at Brown for taking classes that have really good professors just for the sake of taking them, and I think that culture spills over into science classes,” he said.

Jake Moffett ’15, who left the pre-med track, agreed the teaching in BIOL 0200 was enthusiastic and effective but said the teaching in the chemistry and physics courses he took was “disgraceful.”

“We pick up when you don’t want to be there teaching us,” Moffett said. “It’s not even that we don’t want to learn — we’re making you do this job that you hate.”

But professors said they don’t necessarily see teaching introductory courses as a negative assignment.

Bernskoetter said he asked to teach CHEM 0330 last fall because he thought it was important for him to develop the “teacher scholar model.” He said the chemistry department’s strategy of rotating professors through introductory courses gives the course a continued “fresh flavor.”

Stratt echoed these sentiments. “I like teaching intro,” he said. “It’s the hardest thing I do, but … I get to be the person who tells (students) for the very first time about the way the universe works ... and if you can’t be excited by that as a teacher, then what are you doing?”

Miller has taught introductory biology since he came to Brown in 1980. Miller, who was hired to teach a higher-level course on cellular biology, volunteered to teach intro and said he “pretty much had to pick (the department chair) off the floor, because it’s not a course most people volunteer for.”

Miller said he teaches BIOL 0200 to “convert” students to the field of biology.

“I can’t understand for the life of me why any young person in 2013 would want to study anything other than biology,” Miller said. “Everyday when I go the classroom or when I visit laboratories in the afternoon, I want to convince every student that biology is the most interesting and exciting thing in the world, because that’s what I think it is.”

Teach me how to intro

Departments’ methods for selecting who will teach introductory courses vary, with some — such as engineering, physics and chemistry — rotating the duties, while the same professors of introductory biology and neuroscience tend to teach the courses every year.

Valles said deciding teaching assignments in the physics department is a “parameter problem of optimization.”

“We do it carefully,” Valles said. “Our faculty typically don’t teach a course more than three years at a time, so we are constantly swapping courses around.”

When professors don’t volunteer to teach, departments have to “give them a little push or a little shove,” Miller said.

Bernskoetter said a “wealth of resources” exist to help teachers, including workshops hosted by the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning, informal faculty gatherings and peer mentoring within departments.

“If there are colleagues that have taught the intro course in your department and they‘ve done well,” professors should capitalize on their knowledge, Stein said.

Professors can pique student interest by giving students a “professional level view of what science is about,” Stratt said. A professor actively involved in the field of study gives “a different perspective than books and a different perspective than high school.”

“People do vote with their feet, and you have to respect that,” Stratt said regarding student interest in a course. “It’s my job to make them aware of why it’s exciting and interesting.”

While many students enroll in introductory STEM courses near the beginning of their academic career, often eyeing pre-med or engineering tracks, the numbers of students on these tracks drops steeply after the introductory level. The next part of this series will explore attrition rates within these tracks, examining who drops them and why.

-Additional reporting by Jessica Brodsky, Sahil Luthra and Kate Nussenbaum

ADVERTISEMENT