Telephone wires, loosely threaded through the streetlights studding a Jersey highway, crosshatch into the distance across a marbled grey sky. A TV dinner tray, its meat and vegetable portions neatly compartmentalized, sits crooked on a stovetop in a messy kitchen. At first glance, the photographs of Stephen Shore are not necessarily the most striking.

Look again.

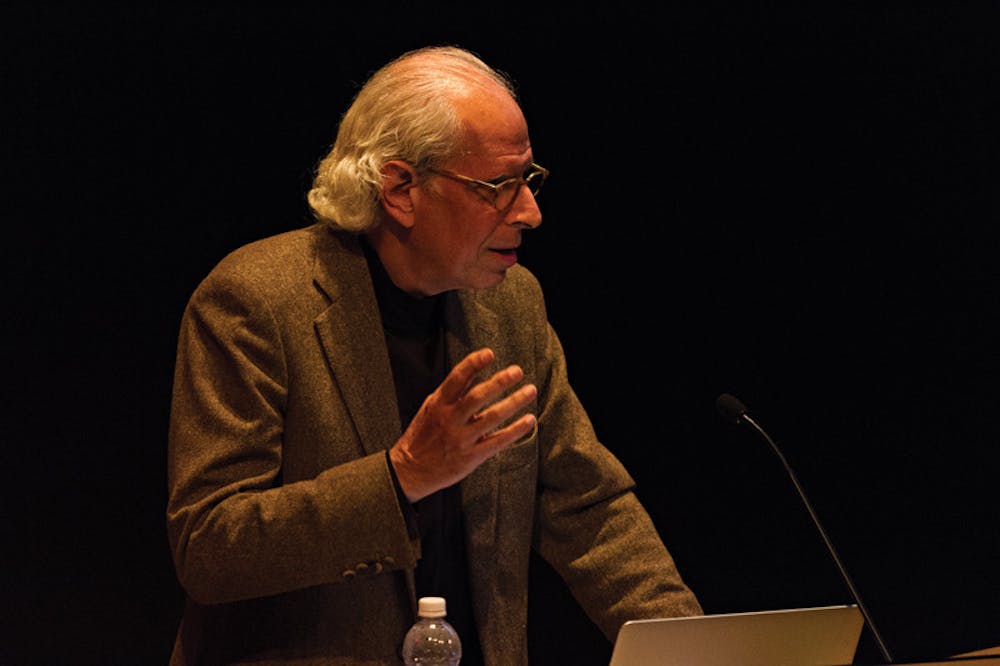

In a lecture Shore — a renowned American photographer — gave Wednesday at the Perry and Marty Granoff Center for the Creative Arts, the artist said his photography is “a means of showing and communicating what the world looks like when seen in a state of heightened awareness.”

The event was part of the Student Creative Arts Council Lecture Series, a program which brings magnates from various creative and artistic fields — including photography, sculpting, architecture and art history — to speak to the community, event organizer Clara Zevi ’15 said.

Douglas Nickel, Andrea V. Rosenthal Professor of Modern Art, introduced the lecture with a brief synopsis of Shore’s career, which he said was “long and studded with impressive milestones.” Such milestones included selling three photographs to the Museum of Modern Art at the age of 14, becoming the second man in history to earn a one-man photography exhibition at the Metropolitan Museum of Art and serving as the director of the photography program at Bard College since 1982.

But perhaps Shore’s most significant contribution to the art world traces back to the 1970s, when the self-taught photographer pioneered the emergence of color photography as a “medium of personal expression,” Nickel told The Herald. Prior to this, color photography was considered “vulgar” and mostly associated with “commercial photography or family snapshots, but not people serious about making art with a camera,” he added.

At the lecture, Shore outlined several “formative moments” in his career, beginning with his uncle building him a dark room in New York City at age six. The next moment occurred at age 10, when he received a copy of Walker Evans’ book “American Photographs.”

“(Evans) had an understanding of the cultural meaning of the photograph, and he was self-aware in adopting a visual style that enacted this vernacular tradition,” Shore said, adding that he feels a “spiritual kinship” with Evans.

In another formative moment, Shore said he worked for and developed close ties with Andy Warhol, the iconic pop artist known for immortalizing the Campbell soup can in the modern art world.

Shore said he spent considerable time absorbing Warhol’s “aesthetic decision-making process” at “the Factory,” Warhol’s studio, adding that he felt a “compatibility” with Warhol as an artist because they both took a “distanced delight in our culture.”

But Nickel told The Herald a key distinction between the two artists is that while Warhol presents an “ironic” critique of consumerism, Shore sees the world with fresher eyes.

“He sees these parts of everyday life, the things you encounter in motels and small towns and street corners, with a sense of wonder and possibility — not the way Warhol would,” Nickel said, adding that “what amounts to a technical issue of using color ends up showing us the potential of paying attention to the ordinary.”

Shore’s next formative moment occurred at a dinner party with Ansel Adams — a well-known photographer who had been drinking heavily throughout the night — finishing at least six tumblers of vodka, Shore said.

“I remember he said with such clearness and matter-of-factness in his voice and lack of affect in how he was speaking: ‘I had a creative hot-streak in the forties and since then I’ve been pot-boiling,’ meaning churning out work for money,” Shore said, adding that this incident prompted him to decide he would seek out some new means of challenging himself whenever he noticed repetition in his work.

Over time, Shore gravitated toward postcards because “they presented a view of very average American culture, but without artistic pretension” and snapshots for their “immediacy” and “vitality,” he said.

To explore these forms, Shore travelled the country, compiling a “visual diary,” which included most meals, people, beds, bathrooms and buildings he encountered.

“It’s almost as if he explores the country as if he’d never seen it before, as if he’s somebody who was born blind and was suddenly given sight,” Nickel told The Herald. “He’s delighted at everything he sees and notices things that everyone else overlooks through force of habit.”

Zevi echoed this sentiment.

“(Shore’s photographs) may look very empty, but they’re actually quite full,” she said. “You look once, and it looks totally regular. But if you look again, you see colors and arrangements that you don’t immediately take into account.”

True to his self-prescription, Shore continually sought new challenges by experimenting with structure, organization, perspective and especially how to “transform a three-dimensional world flowing in time into a flat, static, bound photograph,” he said.

He also said whenever he noticed repetition in his work, he would challenge himself by taking on unfamiliar projects — such as natural landscape, black and white and street photography.

“I know there are certain visual approaches in the way I see and things that’s what I’m bringing to (the photograph), but if I only do that I’m not doing justice to the place and I’m not growing as artist,” Shore said. “I want to be open to changing in response to what I’m encountering and to constantly push in new directions.”

Audience members gave consistently positive appraisals of his lecture.

“It was first time I had heard an artist speak about their work and not have it feel contrived, to have it be explained in a way that I was able to relate to and could see happening,” said Sofia Castello y Tickel ’12.5, currently a research assistant at Brown.

Jayna Arnovitch RISD ’10 also said she appreciated the accessibility of Shore’s lecture.

“What struck me the most was that a lot of what he said was really simply put but really poignant and spot-on,” she said, adding that the result of this was “easy to understand but, at same time, awe-inspiring.”

Ethan Ebinger ’16, who said he was required to attend the lecture for his visual arts class, echoed this sentiment.

“As someone who occasionally has trouble understanding and finding meaning in art, it was really insightful to hear the artist’s perceptions of his work,” he said, adding that he was particularly inspired and impressed by Shore’s “work ethic” of continually seeking new challenges and avenues of exploration.

This cycle of self-imposed obstacle and mastery in Shore’s career is, the artist said, the reason behind his many changes in content and style, including his move towards natural landscapes, a decade of only black and white photography and a series of short, themed photobooks created using a digital camera.

“For me, art is about solving problems and facing challenges, about exploring the world through the medium of photography,” Shore said. “It’s not about making beautiful pictures. Pictures are the byproduct of the activity.”

ADVERTISEMENT