Among metaphors, the Internet as a cloud is especially satisfying: It captures the incomprehensible mass of the globe’s data in one fell, simple, ethereal swoop.

In 2006, Google’s Eric Schmidt introduced the metaphor, claiming the world of data would soon exist “in a cloud somewhere.” Today, “somewhere” has been replaced in the public imagination by “everywhere” — so long as there is Brown WiFi or 3G to get us there. The metaphor makes it easy to forget that the cloud really does exist somewhere, thanks to the wires, widgets, pipes and people that make it work. Welcome to the University’s data center.

Data centers have become the backbone of modern institutions, used to house computer systems responsible for telecommunications and storage of digital information, said Paul Kelleher, director of Brown’s data center. Data center servers are the physical structure of the Internet.

Just one floor underground but unknown to all passersby, Brown’s 24/6.5 operation — manned constantly except on Saturday nights — is responsible for critical tasks ranging from administrative data processing to hosting and running Banner, Kelleher said. Brown’s Computing and Information Services asked that the exact location of the data center not be revealed.

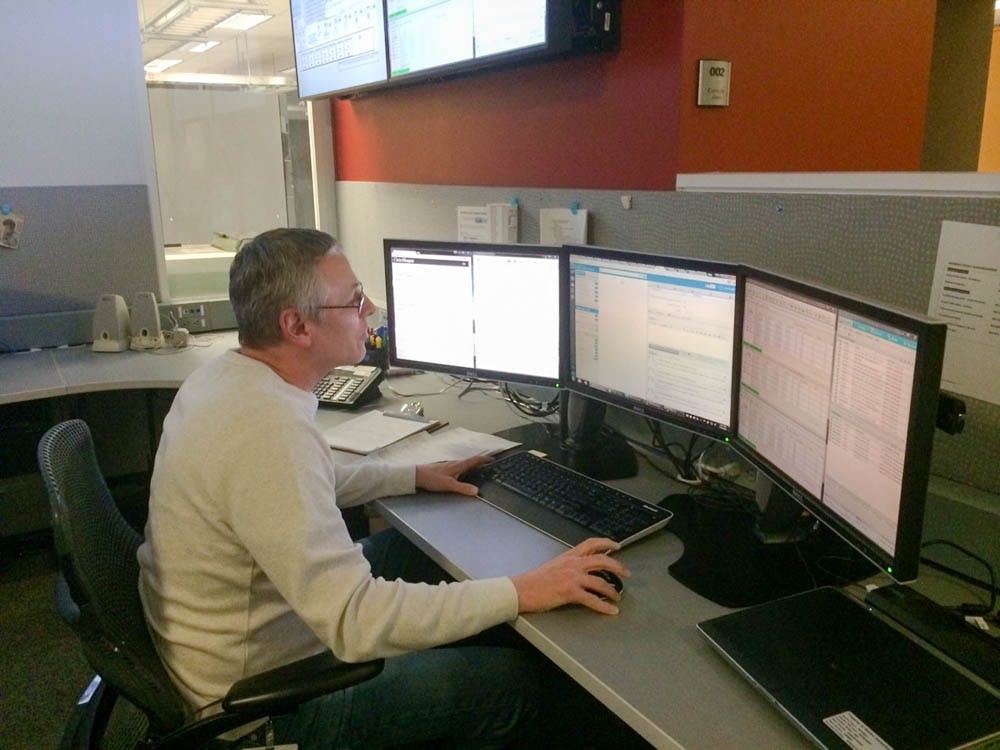

The data center is divided into two sections. The main body is one cavernous, chilled, science fiction-esque room divided into perfect rows of computing machines and the power and cooling systems that serve them. Each row is made up of cabinets; each cabinet is filled with stacks of servers and bundles of wires; each bundle of wire joins with others in a highly organized cable network running across and out of the room. But the heart is the screen-lined console room next door, where teams of monitors closely guard the rows and watch for signs of a malfunction.

“Almost all of our servers are designed so any number of components can actually break, but the service keeps running,” said John Spadaro, deputy chief information officer. The screens in the console room show a software called InterMapper, among other programs, which connects to probes throughout the console room that detect temperature, power supply and functionality of the servers.

“Everything is so heavily redundant that it is not uncommon for things to go down, but it is very uncommon for people to notice — except for these guys,” he said, pointing to the two computer operators currently on duty. “They’re watching, so when they see something go red, they take the appropriate actions.”

“The equipment (takes) a feed from an A-side and a B-side,” Spadaro said, referring to the two power inputs into each server. “If we lose the A-side feed, the B-side stays up — it is capable of taking the entire load. We’re like the guy in your neighborhood when the rest of the neighborhood is dark.”

Inevitably, though, systems fail. The day before Kelleher and Spadaro granted access to The Herald, a few significant issues — most notably a failure in the Duo verification system — had teams from across CIS on conference calls, or what they call bridgelines.

“We had two bridgelines going, which is very unusual,” said Karen Chapman, one of the two computer operators on call in the console room. “In fact, I can’t remember a time where we had a concurrent bridgeline.”

Every few years, the data center invests in new technology, keeping up with increases in storage capacity and energy efficiency. But these increases in efficiency are matched by increased demand for machines, so the data center draws the same amount of power and energy, Kelleher said.

Redundancy, bridgelines, improvements in technology and cables organized with military precision are all impressive, but all are common data center practice. What distinguishes Brown’s subterranean operation is the small team of people who spend hours there and who have done so for decades.

Chapman has worked in the data center for 42 years, Operations Hardware Specialist Andrew Bourgeois for 36 years and Spadaro is in his 32nd year with CIS. Computer operators Sharon Dillon and Victor Trindade both have 25 years under their belts in an industry characterized by change more than most.

“I started at Brown at age 18 in 1975,” Chapman said. “We used paper tapes to start some of our computers and our printers.” As for Bourgeois, he joined the department in 1980 as a night shift operator after being trained through a government program.

The data center Chapman and Bourgeois started in was under the Department of Mathematics and housed on the corner of George Street. They fed computers punch-cards and worked with the IBM System/360 and PDP 11/70, “big boxes that looked like washing machines and held 80 megabytes,” Bourgeois said.

But “demand for computer time grew and the use of that time got cheaper,” Bourgeois said, attributing the explosive growth to cyberpunk science fiction, William Gibson novels and the fact that students were taking to the nascent technology. “So in 1986 to ’87 we started realizing that George Street was not going to make it,” he said. Chapman, Bourgeois and Spadaro all recalled the 12-hour rush during which they physically transferred the computers to their new home.

Three decades — and many iterations of Moore’s Law, which holds that the processing power of computers doubles every two years and which Bourgeois has seen proven — later, all three are still here. Why the staying power?

It benefits the system to have people in place, Chapman said, “so long as they’re willing to change with the times.”

Though a 2010 renovation separated the console room from the server room, it used to be that the people and machines breathed the same air, and operators became attuned to the slightest sounds — not an easy task amidst the machines’ constant droning buzz. “When you worked out in the room, you heard something go wrong before you saw it go wrong,” Chapman said. “You heard a different noise. You didn’t know what the noise was, but you knew it was a different noise.”

Bourgeois, for his part, is familiar with more than just the sounds of machines. As the hardware specialist, he knows better than anyone else their locations, their functions and even their personalities. “We once had a haunted machine,” he said. “It misbehaved from the moment we got it. First we swapped out the card, then the CPUs, then the motherboard. By the time we were done, the only thing that hadn’t been changed was the case. And it still misbehaved. The only explanation was that it was haunted.”

The stakes of Bourgeois’ work are much higher than identifying haunted machines. When he makes a mistake, the entire University can feel the effects. “One time I opened the back of the machine, and the power cords were unsecured,” he said. “When I opened the cabinet, those plugs popped right out and the whole system went down and people knew it.”

The data center computers might soon lose the hand that knows them best. Bourgeois anticipates retiring in the next year to try his hand at new ventures, he said. “I’m playing around with the idea of writing science fiction,” he said. “I have been thinking about a tribute novel to Philip Dick,” whose novel inspired the movie “Blade Runner.”

Bourgeois has been researching the novel for years, but because he always had to be “fresh for his day job” — the one for which the University’s network was at stake, though Bourgeois is too modest to admit his importance — he hasn’t yet found time to write. He hopes that will change soon.

What won’t change, or at least hasn’t since Bourgeois started working, is the consistency of the service provided by the team that runs the data center and, by extension, the services — the cloud — that users simply assume exists.

“There is a very physical element to data centers,” Spadaro said. “Things are spinning. Things are turning.” For decades, the machines have turned, and they’ll keep on turning, thanks to the work of the team in the console room.