We sat down across from each other in the corner of a West Village cafe. How does one even begin a conversation of such colossal proportions?

“I loved your father,” she prefaces.

Those few words disarmed me. In an instant, I was un-composed, emotions rushing like a flood from behind a dam. I loved him, too, I thought, but could not say. Silence was the only steadying force left.

Looking at her was like looking at a broken mirror. She was who I could’ve become, but didn’t. Had I been born 30 years prior, my happy childhood would have been replaced by her fractured one. As it happens, our childhoods had only one similarity: my father’s unconditional love.

Long before having me and my siblings, my father spent every Friday with Sarah for years, and during that time, raised her as his own.

“Why did your mother join The Group?” I asked.

I come back to this question with every former member that I meet. Even so, I feel that it’s an immovable blind spot in my understanding of The Group’s formation.

“She was the daughter of a minister. She got herself out of there, she was valedictorian, she did not have money, she lived in some shitty town in upstate New York. She left, went to college. She was a very good student, but I think like socially she was just—and I think this was true for a lot of people—which was that like not totally knowing how to be in relationship with other people and also being angry, having not the best home life, not the best relationship with your parents, pressure in this way and that way. I think not being religious, being around a bunch of creative people, it started in a way that was different than where it went. I don’t think anybody joined being like ‘I would love if I could join a group where my therapist controls who I date and everything I do and the job I have.’”

I try to envision myself in my father’s circumstances: I’m a sheltered, nerdy, arrogant, 20-year-old Jewish boy from Queens. I’m almost certainly a virgin. I went to college at 16 on a full ride, bearing freshly-healed acne scars and spectacles I’d had for as long as I could remember being bullied for them. On the weekends, I’d go home for Shabbat dinner, where my mother barked at me to finish every last scrap of food on my plate and then did my laundry. After I graduated, I went straight to medical school, all this time having never left the city. And then one day I met a woman —in class or at a party, I’m not sure, but in my imagination, she had spirals of long, red hair running down her back. She promised me sex, intimacy, friendship, art, culture, and drugs, all in one quixotic package. And somehow, she tied up this offer without me noticing the strings attached, and I realized that all this time I’d been so lost, but now, finally, my life could begin.

The disc freezes. I can’t project my imagination any further down this hypothetical trajectory. At this point, I’ve reached the part of a tree's roots where it disperses into tens of prongs diverging in different directions. There are endless permutations of “hows” and “whys” that lead up to joining a cult, but at its core, every recruitment story is more or less the same.

“It started with a bunch of young people who had just lived through the sixties and still believed that the world could be different. Fuck this nuclear family shit, we don’t need this. Let’s have a theater group, we can make our own rules!”

She continues,

“A lot of people in The Group were really smart, really funny. There were all these musicians who were in The Group, and people who were interested in the same stuff. It’s like, I get it. I get the dream of it, and then over time it tightened and tightened and tightened…”

When I first decided to research The Group, I was told immediately that I would hear an enormous range of opinions depending on who I talked to. To this day, there are former members of The Group that are old crooners, endlessly nostalgic for the ideology that they so adamantly believed in. The enduring merit of The Group, they believe, is its good intentions. Communal parenting, therapy, free love—they all seemed like great ideas in theory. The communally-raised kids, though, who never chose these ideologies for themselves, have a different perspective.

Being a child born into The Group, devoid of autonomy, Sarah’s empathy and understanding of The Group’s formation astounded me. I had expected to hear her reflect on her childhood with only resentment and anger, but instead she showed a delicate compassion for the adults that were passive bystanders to her upbringing in The Group.

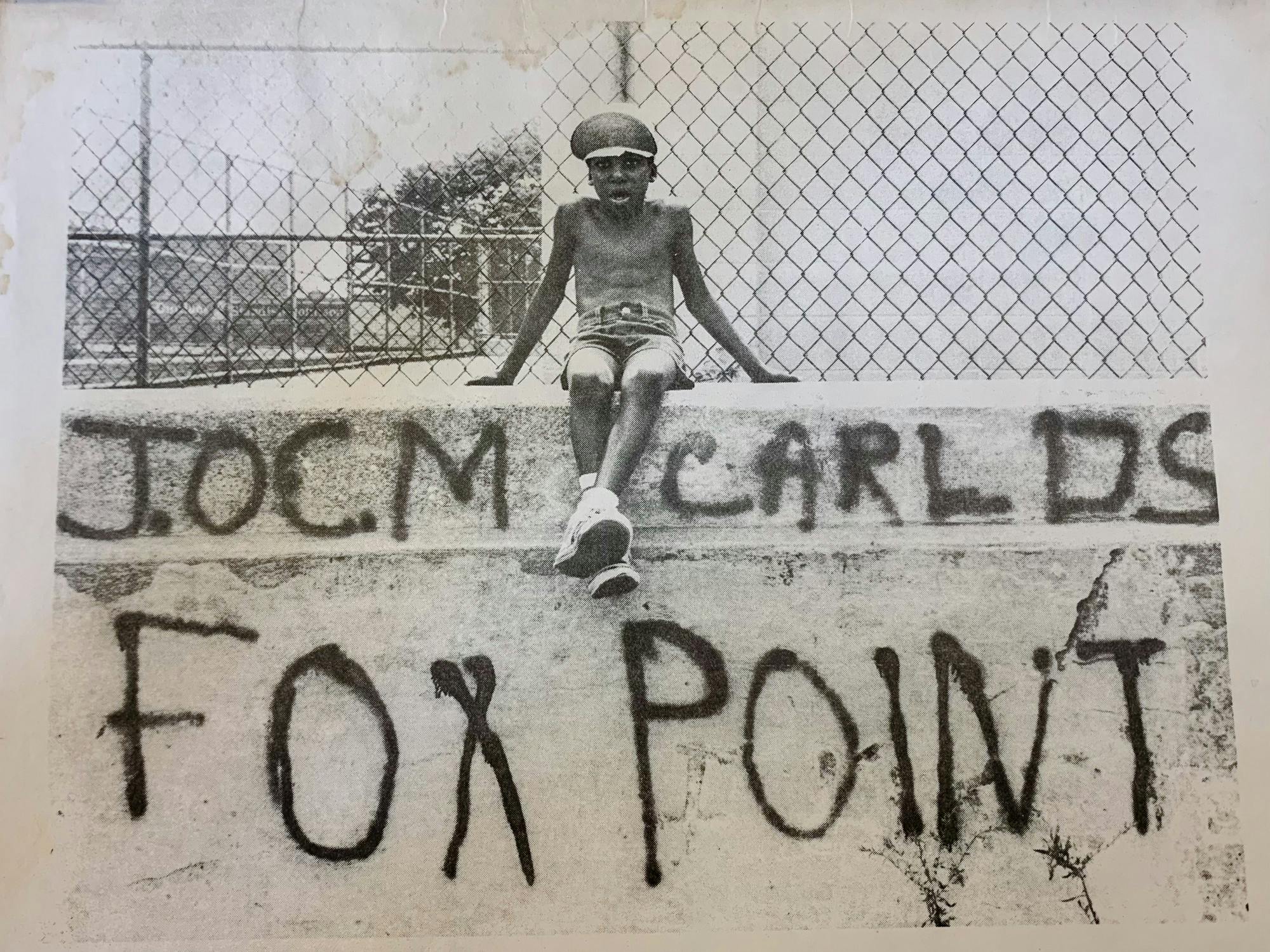

Growing up, she was allotted one day a week to spend with her mother. The rest of her time was occupied by babysitters, and spent at the apartments of other children who lived with her at the group’s shared apartment building. One day a week, she spent with my dad, long before I was even a twinkle in his eye. On those days, he made up stories about King Arthur and the Knights of the Round Table. For her birthday, he bought her a microscope, she told me.

The cult was polyonomous—naming themselves The Group, the Sullivanians, and the Fourth Wall—and polyamorous. Everyone in The Group had multiple intimate connections within The Group, and were encouraged to date people outside of The Group to bring them in as new recruits. They each kept a date book to keep track of their social pairings, both romantic and platonic.

“What was your conception of the cult’s ideology?” I asked her.

“From young, we were taught how to talk about it, so it’s a little hard for me to thread out what I actually thought. I knew that all the grown-ups had date books, I knew that they scheduled their dates. They dated different people at different times of the week. As I’ve grown older I’ve learned that monogamy was really discouraged; you were not supposed to focus romantically on one person. To my mind, that has to do with, again, whether that was a conscious intention or just felt like a convenient, effective way to do this. I think that if you have two people that are in love and just want to be together, how hard is it for them to turn to each other and be like, ‘Want to get the fuck out of here?’ but if you have everybody dating everybody, then everybody stays.”

Non-monogamy was at the heart of The Group’s ideological blueprint, but therapy was its concrete foundation. Whether or not their radical ideologies were established as genuine belief systems or as control tactics is impossible to say. Every member had a therapist with whom they had regular sessions. Referring to such people as therapists is likely offensive to legitimate therapists everywhere, but this was the ’70s, and lying on your resume was even easier without the internet. These loosely defined therapists were trained by The Group, and overseen by head therapist and guru Saul. The therapists had no conception of a “conflict of interest,” and they were often friends with their patients, or dating them. But even more common, they acted as their patients’ parole officers.

These therapists fervently followed the whackjob philosophy of pseudo-psychologist Harry Stack Sullivan, who can probably be credited for the term “mommy issues” even more so than Freud. The Group’s guru, Saul B. Newton, founded the Sullivan Institute for Research in Psychoanalysis, which held that traditional family ties were the root cause of mental illness. The end goal of The Group’s therapy was for you to realize that every single one of your flaws can be blamed on your parents.

A truly devout member, my father preached this philosophy for 13 long years. He met my mom a few years after escaping The Group. I was 16 when I heard this story for the first time.

May 10, 1982

Dear Mother,

You have sent me many letters over the past years asking me to reestablish my “ties” with you. I will never do this, and I will tell you why. I cannot live with a lie. Your version of our relationship is a lie.

November 10, 1985

Dear Mother,

How dare you send me that ludicrous note? In truth, you’ve always hated me and don’t deserve to have a relationship with me. Anyway, it’s too late to draw me back into your narrow, petty, pleasureless world. Don’t try to contact me again. I won’t respond.

For the first time in my life, I had the horrible, intrusive thought that my Dad might not always have been a good person. Memorializing someone can be a treacherous path. It’s all too easy to let nostalgia cast a glowing, angelic light on someone’s past, and for my Dad this is easy to do. I feel more defensive over my Dad’s reputation now than ever before, and I’m desperately afraid of tainting his memory. So, in my exploration of the archives of his life, it has been hard for me to admit to his shortcomings.

My aunt never came to his funeral, and I thought I would never be able to forgive her for this. I was incapable of understanding what grudge could possibly outweigh the importance of mourning a dead brother.

August 20, 1979

Dear brother,

Congratulations on your graduation. I would have loved to share it with you.

I realize now that mourning a loved one’s death might not be a possibility when, after 13 years of absence, you are still waiting for them to come home. I realize now that my aunt and my grandmother grieved for my dad long before I was even born.

For this, I feel angry at my dad. It was his decision to ostracize his family, to sever them from the important milestones of his life. And it was a needless amputation. The cosmic irony is that my dad will never see me graduate college. He won’t be there to meet my future partners, or look after his grandkids. In this fate, I have no choice.

November 16, 1985

My dear brother,

In the short story “The Monkey’s Paw,” the parents wish back a dead son, only to wish him away because the reality did not fit their dream.

That’s how I feel about you.

I am filled with remorse and I mourn the death of the brother I knew.

I am 21 years old now, the same age my father was when he first joined The Group. There’s so much we don’t know about our parents’ lives, and in every case, that ignorance shields us from a hard truth about who they were.

Putting myself in my father’s shoes has felt like a non-chronological dialogue with him; as if now I have the chance to go back and get to know my father at 21, when he was a lost, idealistic, angsty youth. By the time I got to know my father, he bore virtually no resemblance to his 21-year-old self. He’d grown into a level-headed, optimistic, and incredibly selfless person. He was everything I aspire to be; I only hope I don’t have to join a cult to get there.