There was no second of purifying blackness, no raising of curtains or lowering of wires, no mechanized magic at all. Samia strode out to the microphone stand at centerstage, wearing her characteristic wide-eyed fishnets, mid-calf black leather boots, and a tiered white miniskirt that clung to her waist like a fluke.

Then there was her top. It was a tight little v-necked black thing just like what I bought last month from Urban Outfitters—was it the same one? I kept my eyes open until my vision blurred, and for a moment it was me up there, in that top; then my eyes refocused, and with a strange, almost relieved feeling, I ruled it out.

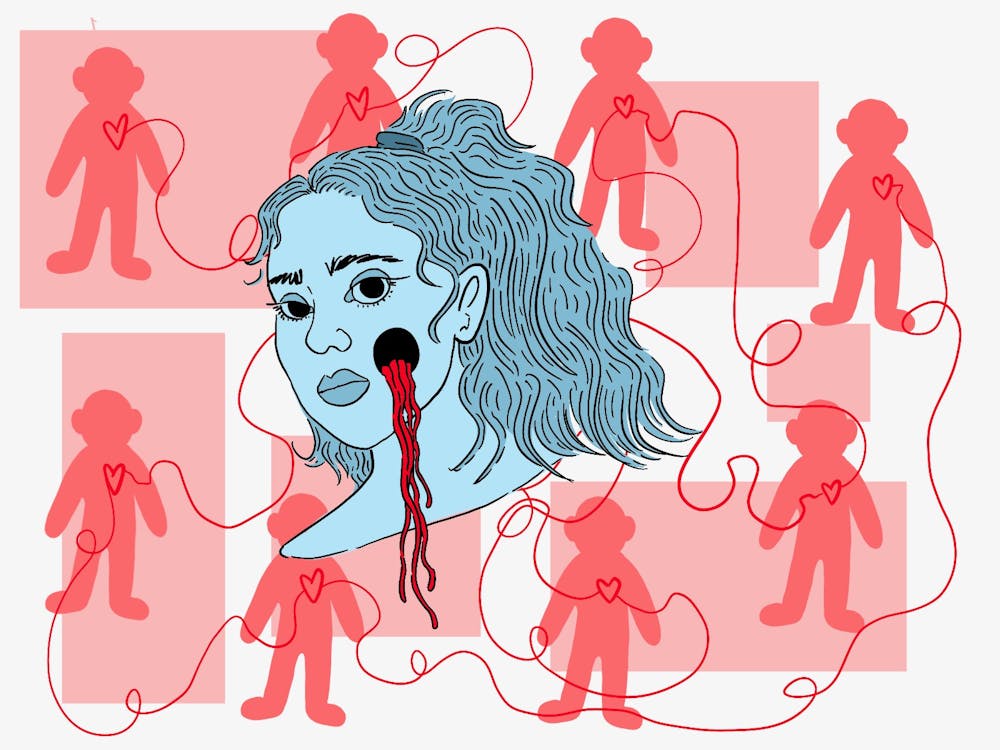

I couldn’t have known it, but what I was feeling then was the beginning of a breakage. A tenuous and contradictory marriage of ideas had enticed me to this concert floor—that paradoxical partnership between identification and deification; humanity and superhumanity; relatability and celebrity that has characterized my, and many other young people’s, relationship to music and its makers. As I looked up at the singer on stage, my whole body chilled. The marriage—or my faith in it—was beginning to crumble.

–

If you don’t count Spring Weekend, I had never been to a real (big, indoor, professionally produced) concert until a few weekends ago, when my housemates and I drove to Boston to see Samia. Samia is a big enough deal to book an 1800-person venue in Boston, but is still relatively unknown compared to the giants of her indie-pop genre (Phoebe Bridgers, Lucy Dacus, Japanese Breakfast, and so on). The occasion for the tour was her sophomore album, Honey, an 11-track display of young-adult angst and occasional delight, oblique anecdotes and crisp turns of phrase, rich guitar backing and the occasional wail of a synth, all guided by a voice of extraordinary depth and versatility.

My housemate Caleb drove us to the concert. There is some point in every city kid’s life where we have to start trusting our twenty-one-year-old peers to steer us down highways going 70. We don’t think about it, I guess. I leaned back in the passenger seat, queued Spotify’s “This Is Samia” on the aux, and turned the volume up as far as it could go.

We cracked jokes and sang along, all half-delirious with end-of-the-week relief and heady anticipation: we were driving to Boston for the joy and glamor of being part of a crowd, for the adventure, for the chance to hear the songs we loved played louder than the car speakers could achieve. But we were also going because some part of us believed—or some part of me did, at least—that Samia, age 26, knew something about life in its most nebulous construction that we did not. She had the answers. And maybe if I heard those answers straight from her, in her magenta, magnetic voice, well—what would happen, exactly? Would all my problems be solved? Would I magically get over my ex, discover a higher calling, be cured of all anxiety and ambivalence, and ace my history paper (for good measure)? Would everything, suddenly, make sense to me?

I could not have said any of this out loud, or even thought it to myself then, without laughing in derision. But there I’d been, riding shotgun, barreling north on I-95 to hear Samia’s next divination.

–

And here she was in front of the mic. Samia’s hair was half-up, half-down, and chased itself down to her lower back in a frizzy free-fall. Her chin stuck out to the left a little bit, like mine. I looked her up and down in disbelief: she was all bone; five feet and six inches of acute angles. She brought her hand up to cover her parted lips. Then she opened her eyes wide in a gesture of shock.

Samia, goddess, prophet of the night, looked at her audience—at least a thousand black crop-tops and fishnets and bony hands holding-barely-horizontal IDs—and said into the mic:

“What are you doing here?”

–

Some of you might understand it already. It’s that feeling when a song—through its eviscerating, clarifying precision—makes you cry, but right afterwards you always feel better. From that moment on, you hold this singer responsible for your brief redemption. You invest in her a certain special trust. As we walked into the Boston venue, I held this trust for Samia; I thought she had the answers.

Let me try again. There is a natural human instinct, among all of us, although maybe especially among young people, to look for a guide, a God, or an idol. Music and the people who make it have always been well-suited to fulfill this desire for their listeners; in fact, the world of pop music is bolstered, if not altogether built, by this wish and the promise of its fulfillment. To set a group of words to music—to make them lyrics—invests in them a power that they would not have alone on the page. Set to music, words are imbued with the inevitability of melody and its resolution, and the more times a song is played and the more familiar it becomes, the more inevitable the melody, and thus the lyrics, begin to sound. In short, music is a reifying force; it has the capacity, from the music historian Richard Taylor’s book, to “weaken” the “intellectual resistance” of its listeners to any message that its lyrics hold. It is with this logic that I explain to myself the transfiguration that I witness between my first, and third, and twelfth rounds through any new album: a subconscious but undeniable shift from an interpretation of the music as the singer’s words to something more like The Word.

The telepathic, or even prophetic, power that I and others my age tend to attribute to singers like Samia is reinforced by the sense that these artists are really just like us. This tilt towards “relatability” has already been analyzed to pulp by smarter people than me. But relatability, the process or feeling of identification with the artist on the stage, is immensely powerful. It offers a seductive comfort, a sensation of secret companionship. I haven’t got it all figured out just yet, which is a hard thing to admit, but when I listen to Samia, I don’t have to. She hasn’t got it figured out either.

–

But hasn’t she? Samia stood at center stage, stock still, the only sharp-lined thing in a swirl of white light. She was angelic. When she began to sing, her voice was as strong as I remembered from the recordings: rich, pure, entirely sure of itself. It soared into the crowd and we caught it and held it for a second and threw it back to her from our own, soon-to-be-exhausted lungs. She was our leader and we were her acolytes. Samia was a star.

When we seek to identify with artists, our goal is not to dethrone them. We don’t want that at all—we want to have our problems shared, articulated, sorted, and then transfigured into art, so that all of a sudden they are both beautiful and meaningful, instead of ugly, useless, and mundane. What we really want is for the stage to be a mirror—but not just any mirror. We want a magic one, one we can peer into and see someone bigger than ourselves. Someone shinier and surer than who we really are.

Listening to music on AirPods or over a car speaker lets the mirror do its magic. Recorded music brings just the right amount of alienation from an artist herself, and from the visible production of stardom and “relatability.” Samia’s problems never take on substance or flesh: her trials are radio frequencies; her fraught subjectivity is a side-profile photo on an album cover. With struggles that intangible, it’s plausible to think that singing could be enough. That to understand and package and tell stories about what hurts might be all it takes to make those things disappear.

Here in Boston, it was different. Just as I had settled back into my enjoyment of the spectacle, Samia hiccupped. She stopped singing for a moment. She asked the band to start over, but in the brief, music-less pause, I looked up to the spotlights above her—to the machinery, to the source of the blurry white light. If the lights turned off, I realized, it would just be her (Samia, age 26, seven years older than me) and her bandmates, and some cords, and a drum set, and a thousand of us in the audience, waiting for her to show us the way. Here was the breakdown of the marriage; here was the paradox made visible. Samia did not have it all figured out. She was not—could not possibly be—both god and mortal, both superhuman and real.

And turning her problems into art seemed like a woefully inadequate solution. I turn my problems into art all the time; I storytell to my friends, I find patterns, I package. “I’ve got it!” I say, or, “That was the problem, the whole time.” And then in a year, or more often a week, I turn around and I say: “No, I was wrong.”

Samia is 26. What makes her any different?

What in the world were we doing here?

–

If there was any answer to this, it was during “Stellate.”

Maybe ten songs into Samia’s set, she started singing one that I hadn’t heard before. For reasons that are peculiar to me—irrational, but legible, in my own way—the ballad cracked something inside of me that had been brittle for weeks. I started to cry.

They were good tears, tears that would make me feel better by their end. But for three and a half minutes, I was crying. My housemate Coco saw me stop dancing, and, wordlessly, pulled me into an embrace; we stayed like that until the last chord. What were we doing here? This. Maybe I was wrong to imbue Samia’s lyrics with the meaning that I did, but there is something different, and beautiful, in that collective investment in meaning.

What the meaning is doesn’t matter. Music gives us space to think differently—to interpret and respond to harmonies and lyrics in divergent, and even contradictory, ways. But ultimately there we all were, listening to Samia, agreeing on our basic affinity with it. Coco could not have known what I was thinking when “Stellate” made me cry. We never talked about it. But they were there all the same.

On the drive back home, I felt shaken, but happy, too. I sat shotgun and cued up a long list of songs in Samia’s genre—but none by her; we needed a break. Caleb was at the wheel, driving fast down the highway back to Providence, and I thought fleetingly about youth and infallibility and trust. Because we do have to trust each other, in the end: not as gods, not as idols, but as humans, our faces tilted up at a darkening stage.

Lily Seltz is a former staff writer for post- magazine and new writer for the The Herald. She studies English (Nonfiction) with a certificate in Migration Studies. She is always searching for a better bagel.