note: contains version translated into Spanish at the end.

The mailroom worker calls my name like they've never heard a name like it before, because they've never heard a name like it before. I know it's a box from my mom; her big black Sharpie font says her name and mine. For a second, we are together. All the times we have hugged and every time we could not.

I put the box in the bag that she told me to bring because she said I would need it. “Que pena que vives tan lejos,” I remember her saying as the smooth tunes of Samara Joy aligned with my steps.

I use the scissors she bought for me when I moved in to rip through the five layers of tape. Because, as her voice reiterates in my head, “USPS always beats up the boxes.”

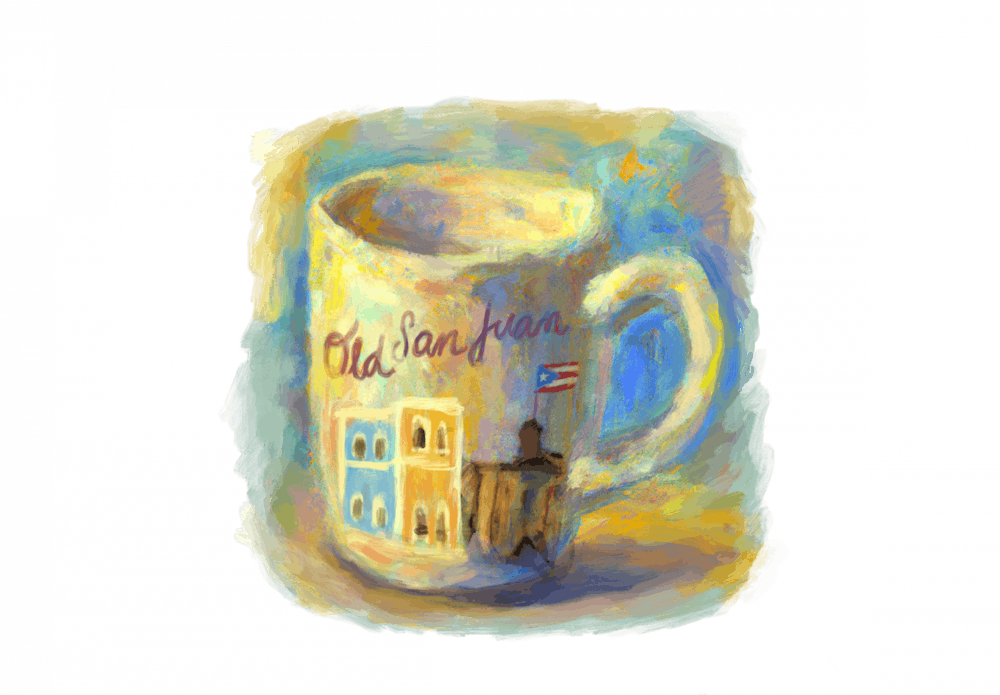

There's always tissue paper and two handwritten notes: one from her and one from my niece. Those are the contents I value most. This time there is bubble wrap. As I peel back the layers I realize it is a mug, bright with color. It comes with a spoon I won’t use because I don't add sugar to my black coffee.

The mug says “Old San Juan, Puerto Rico.” There's a vibrant pattern of buildings from this area, one on top of the other, and a Puerto Rican flag painted on the centered door. El Morro is off to the right with a Puerto Rican flag on top, the ocean behind.

Here, at my dorm desk, I realize I don't want a souvenir from the place I come from. It means I have left. I don't want a Puerto Rican flag. It means I have left, and that the packages will keep coming.

Whenever the Puerto Rican Day Parade played on our TV, I saw flashes of red, white, and blue that did not mean the United States but meant Puerto Rico. I didn't understand the fascination behind a flag whose blue was changed to a darker hue so it would emulate the American flag. Our flag, whose blue once meant sky; white, independence; and red, revolution.

From 1948 to 1957 La Ley de la Mordaza prohibited Puerto Rican people from displaying or even owning our flag; it was seen as a sign of rebellion, of unacceptable Puerto Rican nationalism. I didn't see the flag as anything more than a symbol of the fact that we’re still a colony. But now it’s signifying that we are allowed to be visible, to see each other.

I still don't want a souvenir from Puerto Rico. I don't want to have to explain to my friends why I don't want it because I don't want to have left. I don't want to take pictures of every Puerto Rican flag I see hanging on rear-view mirrors or poking out behind fences. I don't want to put a Puerto Rican flag pin on my backpack.

But I do.

The mug sits in a case with a plastic front cover so you can peer into the cityscape. I think I understand why they make it transparent: so you can display it, and hold on to it like a semblance of the puertoricanhood you want to claim. I want to be recognized as Puerto Rican, not asked where I'm from. I don't want people to tell me that my American accent is really good or ask if it's snowing back home. I don't want to say I'm from Puerto Rico and for people to respond, “Oh that's so cool I went there on vacation once!” or, “Sick I've always wanted to go, it's so exotic, the people are so warm, I've heard.”

Recently, whenever I tell people I am Puerto Rican, they ask me where I'm from again. They don't assume I come from the island. They assume I'm from the diaspora. Their eyes widen and they shake their heads in disbelief—I can't really believe it either. They look at me like they've never seen a Puerto Rican before, like they've never seen before. I don't really know why this image is so vivid in my head, maybe because I have seen this face so many times. I know they just want to ask me how I feel in this snow now. I don't know how I feel, in this snow, now.

The “people are so warm” is true. We are. It is normal—customary—to greet everyone with a hug and a kiss on the cheek. To dance in the streets when there's music playing or when you have the rhythm within you. To cheer, to yell, to make a beautiful noise. To speak Spanish so uniquely only we can decipher it.

Still, I don't want this mug. I am not from Old San Juan. I am not from San Juan at all, not even the North. I am from what old sanjuaneros would call La Isla (in an attempt by the elite class to distance themselves from the “Others”) as if we weren't all from the same island. I'm from the South, where seeing a tourist is as rare as seeing flamboyants bloom in May. Where you are always five minutes from a river, a beach, the mountains, or a broad field of dry, dry soil. Where the bougainvilleas line our fences, crowning each home with mosaic delight. Where cacti can grow next to pomegranate trees and the morning dew evaporates as quickly as it lays on the bluegrass.

Still, my mother will keep sending me boxes and sign every letter with the name of our Town, City surrounded by hearts. Still, in our daily FaceTime calls, she will show me the backyard: “Para que no te olvides de nuestra casita.” Still, the distance will make me want to use the damn mug.

[author’s note]: After seeing the original article in English, my grandmother asked if I could translate it so she could enjoy it too and, of course, I did.

El cartero dice mi nombre como si nunca antes hubiera oído un nombre así, porque nunca antes ha oído un nombre así. Sé que es un paquete de mi madre; su letra enorme escrita en Sharpie dice su nombre y el mío. Por un segundo, estamos juntos. Y recuerdo todas las veces que nos hemos abrazado y todas las veces que no hemos podido.

Meto la caja en la bolsa que me dijo que trajera porque me supo que la necesitaría. Recuerdo sus palabras, "qué pena que vivas tan lejos”, mientras las suaves melodías de Samara Joy se alinean con mis pasos.

Utilizo las tijeras que me compró cuando me mudé para rasgar las cinco capas de cinta adhesiva. Porque, como su voz repite en mi cabeza, "USPS siempre destroza las cajas".

Siempre hay papel de regalo y dos cartas: una de ella y otra de mi sobrina. Esos son los contenidos que más valoro. Esta vez hay papel de burbujas. Al retirar las capas, me doy cuenta de que es una taza de colores vivos. Viene con una cuchara, cual no usaré porque no le añado azúcar al café.

La taza dice “Old San Juan, Puerto Rico”. Hay un vibrante dibujo de edificios de esta zona, uno encima de otro, y una bandera de Puerto Rico pintada en la puerta del centro. El Morro está a la derecha, con la bandera encima y el océano detrás.

Aquí, en el escritorio de mi dormitorio, me doy cuenta de que no quiero un recuerdo del lugar de donde vengo. Significa que me he ido. No quiero una bandera de Puerto Rico. Significa que me he ido y que los paquetes seguirán llegando.

Cada vez que presentaban La Parada Puertorriqueña en nuestra televisión, veía destellos de rojo, blanco y azul que no significaban Estados Unidos, sino Puerto Rico. No entendía la fascinación que ejercía una bandera cuyo azul se cambió a un tono más oscuro para que emule a la bandera estadounidense. Nuestra bandera cuyo azul antes significaba cielo; el blanco, independencia; y el rojo, revolución.

De 1948 a 1957, la Ley de la Mordaza le prohibió a los puertorriqueños exhibir o incluso poseer nuestra bandera; se consideraba un signo de rebeldía, de nacionalismo puertorriqueño, algo inaceptable. Yo no veía la bandera más que como un símbolo del hecho de que seguimos siendo una colonia. Pero ahora significa que se nos permite ser visibles, nos permite vernos.

Sigo sin querer un recuerdo de Puerto Rico. No quiero tener que explicarle a mis amigos por qué no lo quiero, porque no quiero haberme ido de la isla. No quiero tomar fotos de todas las banderas de Puerto Rico que veo colgadas en los retrovisores o asomándose detrás de las verjas. No quiero poner un pin de la bandera de Puerto Rico en mí mochila.

Pero lo hago.

La taza viene en un empaque con una tapa de plástico que permite ver el paisaje urbano. Creo entender por qué la hacen transparente: para que puedas exhibirla y conservarla como una semblanza de la puertorriqueñidad que quieres reivindicar. Quiero que me reconozcan como puertorriqueño, no que me pregunten de dónde soy. No quiero que digan que mi “acento americano” es muy bueno ni que me pregunten si está nevando en casa. No quiero decir que soy de Puerto Rico y que la gente responda: "¡Qué cool, fui allí de vacaciones una vez!" o "Wow, siempre he querido ir, es tan exótico, la gente es tan cálida, he oído.”

Últimamente, cada vez que le digo a la gente que soy puertorriqueño, me vuelven a preguntar de dónde soy. No asumen que soy de la isla. Asumen que soy de la diáspora. Sus ojos se abren de par en par y sacuden la cabeza con incredulidad. Me miran como si nunca antes hubieran visto a un puertorriqueño. Realmente no sé por qué esta imagen está tan vívida en mi cabeza, tal vez porque he visto esta cara tantas veces. Sé que sólo quieren preguntarme cómo me siento ahora en esta nieve. No sé cómo me siento ahora en esta nieve.

Lo de que "la gente es tan cálida" es cierto. Lo somos. Es normal, habitual, saludar a todo el mundo con un abrazo y un beso en la mejilla. Bailar en la calle cuando hay música o cuando llevas el ritmo por dentro. Animar, gritar, hacer un ruido bonito. Hablar un español tan único que sólo nosotros podamos descifrarlo.

Aun así, no quiero esta taza. No soy del Viejo San Juan. No soy de San Juan en lo absoluto, ni siquiera del norte. Soy de donde los viejos sanjuaneros llamarían “La Isla” (en un intento de la clase elitista de distanciarse de los "Otros") como si no fuéramos todos de la misma isla. Soy del Sur, donde ver un turista es tan raro como ver florecer flamboyanes en mayo. Donde siempre estás a cinco minutos de un río, una playa, las montañas o un amplio campo de tierra seca y reseca. Donde las trinitarias bordean nuestras verjas, coronando cada hogar como un mosaico de delicias. Donde los cactus pueden crecer junto al palo de granadas y el rocío de la mañana se evapora tan rápido como se posa sobre el césped.

Aun así, mi madre seguirá enviándome cajas y firmará cada carta con el nombre de nuestro Pueblo, Ciudad, todo rodeado de corazones. Aún así, en nuestras llamadas diarias por FaceTime, me enseñará el patio: "Para que no te olvides de nuestra casita". Aún así, la distancia me hará querer usar la maldita taza.