Meet Tom.

Tom is an amalgamation of boys (men?) that my friends, or friends of friends, or even I have briefly dated. These are men at Brown and beyond who have been dubbed, classed, and commodified: the performative male, the lonely male, the lit bro, the film bro, the skater boy, the DJ, the sensitive man, the boy in need of saving, the “ran-through,” the “not-all-men” man.

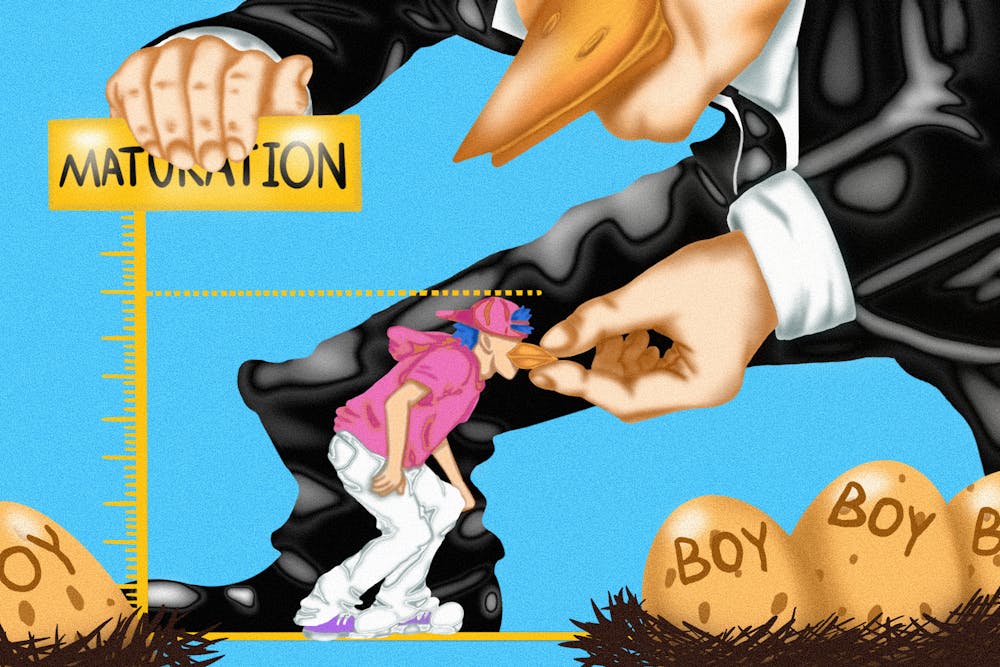

Tom is not performative; he is simply being himself, following the timeline laid out for him. He is taught in youth to suppress all the emotional practices that are hallmarks of psychological maturity. He inevitably gets his heart broken by his first girlfriend. He finds solace and community in a subculture after this cathartic experience. He rekindles his inner child and feminine openness to what he does not know. He reckons with the relationships in his life, and, even though he doesn’t text his guy friends often, he feels they have his back, a sort of pack mentality. He can feel his frontal lobe developing and he likes it, the way he is more self-aware, how heads turn when he walks down the street, the feel of his lengthened stride and larger dick. If Tom is performing, it is only in the ways that we all are, unconsciously, all the time, in reaction to social and cultural norms that we did not consent to. Tom's theatrics are a reaction to being 'seen' as part of a group, dissolving in form, escaping the rat-race of emotional destitution, taking pleasure within this new social order. Come Tom, come all.

I should clarify: I’ve had a series of Toms in my life, one after another. With time I’ve become far more interested in chronicling the way these men were raised rather than the way they currently act. I’m perplexed by an ingrained pattern among all Toms: a central inability to express what they feel.

I recall being in a club in Berlin this past June with one particular Tom. We were Americans on a study abroad program in a foreign country. Through my glasses, I could see dozens, if not hundreds, of individuals older than me dancing in a square of their own making. I remember the sight of Tom, flicking his wrists in the way American men do, moving his body jaggedly, with far too much exposure of his drunkenness. His lips were moving, but I could not hear. He motioned for me to move closer to him. His breath was inches from my face and Pilsner wafted from his mouth. He began to say:

“I’m so fucking old. I’m 23. I’m kind of just a 23-year-old boy when you really think about it.”

Looking at him from across the club’s abyss—this hedonistic, ego-obliterating safe haven that only came to exist because of the fall of the Berlin Wall—I came to realize Tom was stuck in a perpetual adolescence, a prolonged boyhood induced by culture.

I called my mother for advice.

“Men are like birds,” she said, an ocean between us. “When their feathers get ruffled, when things feel a little too serious for them at your age, you have to just let them fly away because, sometimes, they’ll come back.”

Suddenly, I imagined myself shrinking. Through my vision I could see my body becoming smaller, my hands less wrinkled and my fingers less long. I inhabited the body I had in sixth grade.

In this vision, I sat in my home kitchen, in Texas. I faced my parents, although I looked away from them.

“Why are the boys so immature?” I begged for an answer. I admitted I was drifting away from childhood male friends who, overnight, seemed aloof, reticent, in a different world I was not allowed into.

“Boys develop and mature slower,” they told me.

As a child, the narrative spoon-fed to me by authority was as follows: I was not like the other children; I was hyper-aware, self-sufficient. I remember the feeling of tears falling out of my eyes like flies, these itchy things I couldn’t stop. I couldn’t figure out why I felt a sense of disgust watching the other boys goof off in class, mock the girls in our grade who were just starting puberty, slap and punch and kick each other in the name of love.

I’d like to think this illustrates what many women and queer people experience from a young age: a heightened awareness of power dynamics, issues of safety and discomfort, and a recognition of inequities within the social structure. What may be seen as maturity could instead be seen as accelerated development, a so-called maturation that happens without consent.

Research shows that girls tend to develop superior emotional awareness and communication skills at an earlier age, but developmental timelines don’t exist in a vacuum. In the American context, girls are often praised for expressing emotions like vulnerability and empathy, even as they are forced to take on caretaking roles within the family. Meanwhile, boys are systematically socialized to suppress emotions, particularly those perceived as "weak" or "feminine," such as sadness, fear, or sensitivity.

In such a system, it is only inevitable that so-called “sensitive men”—that is, Tom—are unable to communicate their emotional states, even as they are aware of them. A phantom organ to which they have no access.

The phrase for this is the normative male alexithymia hypothesis, coined by psychologist Ronald Levant, who observes that expressions of hurt, fear, and attachment are out of reach for many men due to gendered socialization. Alexithymia literally means “without words for emotions.” There is even a scale to measure this gap in language.

Dating is a fairly recent historical event, and, taking into account that male adolescence is a newly prolonged construct (during the Industrial Revolution Tom would have been at work in a factory before he even hit puberty!), I can’t help but wonder how he came about, how America raised him, birthed him, not once but twice. The women in his life, too: his mother, his first girlfriend, and the women that follow.

As a trans woman, I am fascinated by the ways in which I disrupt these prescribed social timelines. At the same time, I am frightened by how I am mythologized by men, seen as a fantasy or someone who gets “both sides of the coin,” someone with whom men can commiserate about their upbringing and traumas.

In a relationship, one becomes acutely aware of the way their actions correlate to someone else’s feelings and personal histories in a way that friendships do not necessarily demand. Relationships are said to take you out of the hamster wheel of futility, showing the importance of yourself, because you are no longer just a person but someone with a purpose, who receives imbued meaning in a world that is often confusing and contradictory.

Your upbringing has rendered you inarticulate. You get into a relationship anyway. You crave the care you received in adolescence from your mother. You crave to communicate the incommunicable. You attempt to deposit these emotions, and you land on your girlfriend. You know this fantasy is brittle, and you fail to recognize that no one can fulfill 100 percent of anyone’s needs. You feel a sense of loss when it is over, one you can’t put words to. You disavow your ex. Time passes and you start to believe that you have changed. You meet new people and newfound interests. You connect with them over this subculture. You are not “countercultural” but still feel like part of something bigger than yourself. You think this makes up for the pain of losing access to the emotional expression you once had. You rid yourself of the emotional implications of losing that relationship. You are grateful that your object of affection is now indisputably an object rather than a woman, and you are grateful that the feeling of that object is warm, almost as warm as her body.

An American upbringing promotes the idea of newness, that you can always do better, that you can change. The dream is alive.

This fantasy is not limited to dating.

The late literary theorist Lauren Berlant refers to this relationship as “cruel optimism” in her eponymous novel: an attachment to ideas, objects, or relationships that are actually obstacles to one's flourishing.

“Recognition is the misrecognition you can bear,” wrote Berlant. People often settle for the flawed, distorted, or incomplete forms of recognition available to them, for recognition would simply be too traumatic, too painful. Sound Freud-miliar?

If, after boyhood, Tom recognizes his own isolation, but is unable to voice the hurt and vulnerability he feels, this attachment might be what is sustaining this system of voicelessness in the first place, not the potential fulfillment of it. (He frames it as: I love my independence and freedom.)

A friend recently said: “Sensitive men are sensitive about their own feelings, and you think that because he’s emotional, he’s emotionally in-tune. But he’s not.”

Why has Tom risen now? I theorize that social media sorts, archives, and mangles people into sanitized genres; these genres are made accessible on the level of aesthetics through globalized trade and fast fashion. This aestheticization occurs in response to unstable economies and futures, inspiring the desire to claim control over one’s image; surveillance culture has only now awakened men to the feeling of being watched. (In Berlin, I had to tape my phone before heading into any club.)

Universalist ideas of Tom are, of course, perfunctory. It would be paternalistic to claim that I know Tom’s inner psyche or the processes that drive him. I don’t. It is impossible to inhabit someone’s unconscious, and it goes without saying that Tom is not a real person, that no single individual can be easily collapsed into an archetype. Not even Tom necessarily ‘knows’ what he’s thinking, nor do any of us.

My argument is not that Tom is simply misunderstood, or even that Tom is bad—far from it. Tom is undoubtedly an anti-fantasy, a projection. But there is something to say about how, now, there are simply so many Toms; something perplexing about how Tom does not have the language to explain what he feels to the women he dates because society confiscated it from him before he could speak; something genuinely concerning about how patriarchal social development stunts manhood while prolonging boyhood; something depressing about the image of Tom, spent and heaving as a baby, using his body to express language to his mother; something uncanny about the image of Tom, spent and heaving as a 20-year-old, on top of a different woman, half-inserted, using his body to express language to her; and most of all something arresting to the ways in which dating Tom has brewed an affective economy of frustration, despair, and repetition among many of my friends.

Tom is not just a new phenomenon but a paradoxical one. Tom is just self-aware enough to speak about his subjectivity, even as he fails to break through it.

Picturing Tom from afar, standing in all his glory, I realize we are all Tom, no matter how much we wish otherwise. We are the “man of the house” even when we don’t want to be. We are told of the need to be emotionally regulated and stable even when social conditions incur mania. We strive for the ‘good life,’ sharing clusters of promises about people that they cannot fulfill.

Yet even if we are all Tom, we are not all men, which is to say language does not inevitably fail those socialized to express their feelings. Just as memory is a recreation of something that was, language is a recreation of something that is.

Our fantasies rely on imprecise language and feelings as interpreted by language. Language is something that carries baggage, structures our thoughts, serves as the mode of living that decides how we name our inner conscious, yet is nonetheless something we do together. Though emotional maturation is an individual concept that is influenced collectively, we carry the baggage of everyone around us.

And I do not want to be carrying around bird feed.