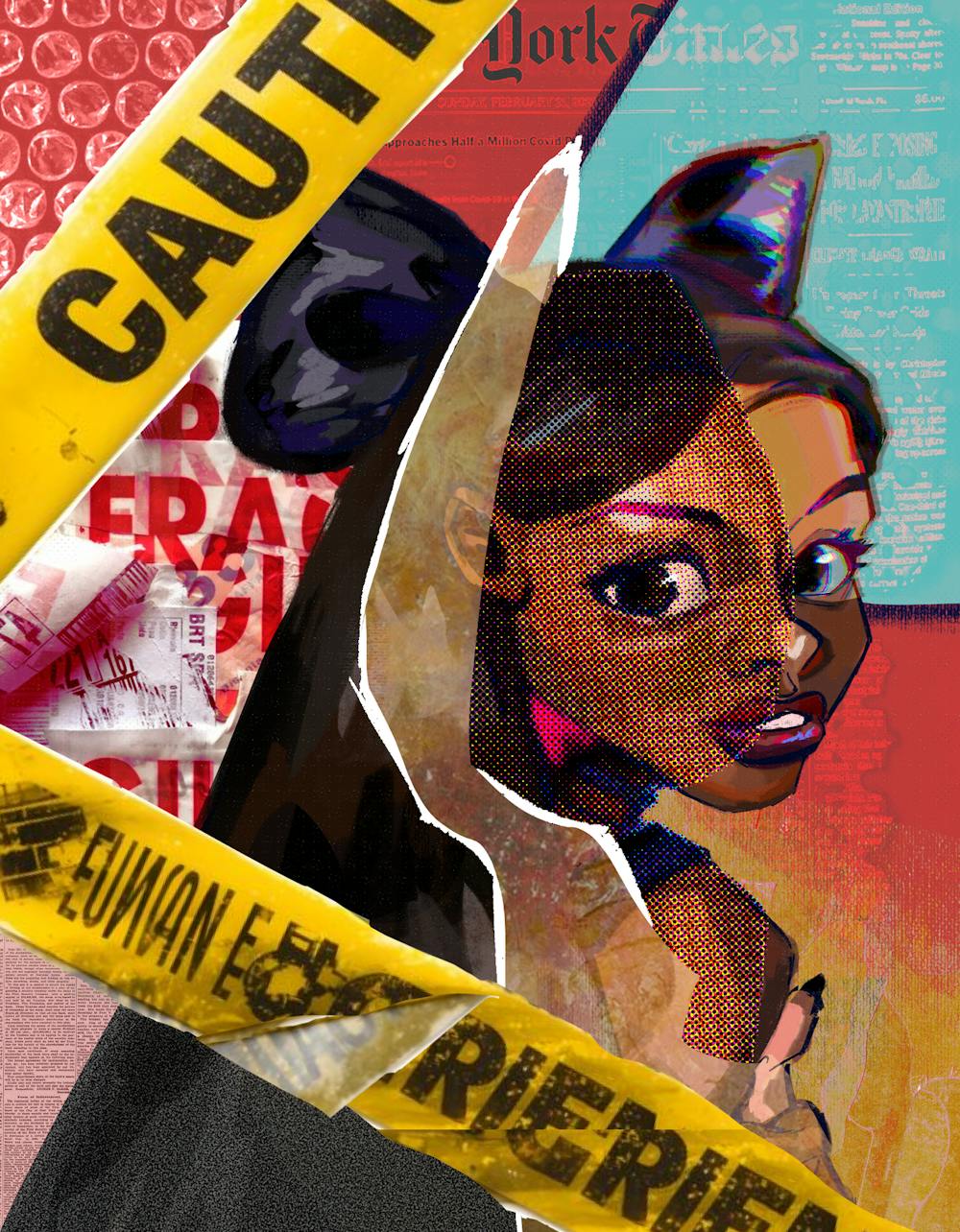

If you’ve ever had a Twitter account or are in touch with popular culture in the US, you have definitely encountered the controversial character that is Azealia Banks.

Sometimes comedic, many times off-the-rails, she always finds the time to make a Twitter thread or a series of blackout stories ranting on Instagram at 3:00 a.m. about current pop culture topics. From entire countries like Ireland to unproblematic artists like Bebe Rexha, no one is safe from getting dragged by Azealia Banks. In fact, I am almost sure that if I were to post this on Twitter and tag her, I would get a taste of my own medicine; she is known for searching for tweets and posts about her and responding to them. Sometimes there is nothing to do but take her rants in, as her humorist approach and breakout hits like “212” and “Luxury” are reminders of her potential as a performer and a lyricist. However, in recent memory, her off-kilter opinions and scarce musical output put into question how much I can support, or at this point, even enjoy her past music.

Growing up in Harlem and moving through a short-lived career in acting and performing arts, Azealia started releasing music under the name “Miss Bank$” around 2008. She released a few singles—one of which, “Gimme a Chance,” gained online traction and turned the heads of household names like Diplo. This led to a developmental record deal with XL Recordings, one she would end up losing a year later.

After losing that record deal, Azealia struggled to break through in the music industry, going back and forth between Toronto and New York, making music and working at a strip club to make ends meet. During this time, she pivoted back to her real name and released her official debut single, “212.” This track took the electronic underground scene by storm, giving her the platform to become one of the most well-known rappers of the 2010s.

Her rise to fame as a self-made artist made Azealia a relatable character, an underdog who became popular because of her pure talent and ambition. However, this image quickly became complicated as she started getting involved in unnecessary drama with peers like Lil’ Kim and Iggy Azalea (whom she famously called her albino child she randomly gave birth to in prehistoric Pangea). These hilarious unprovoked altercations shaped the way she was perceived in pop culture at the time, hindering some of her appeal and likability.

During a famous altercation on Twitter between Azealia Banks and Lana Del Rey in 2018, Lana expressed her frustrations with Azealia, pointing to her slow decline as a prominent figure in alternative music spaces. Lana posted, “Banks. You could have been the greatest female rapper alive but u blew it,” likely referring to how her controversial opinions and affinity for starting conflict with whoever crosses her path have gotten in the way of her becoming one of the most respected female rappers in the industry. This is crucial as Lana was one of the first public figures to support Azealia, featuring her in a remix version of her song “Blue Jeans.” If people who were there for you since the beginning of your career are now turning on you because of your behavior, maybe you should reflect inward.

Even so, Azealia is viewed by many as a misunderstood character, ostracized because she expresses her opinions unapologetically. This is relevant when you consider her positionality as a Black woman in the music industry during the 2010s. Black artists, especially women, in the music industry are often subject to subjugation, predatory record deals, and public shame. Society seeks to control how they express themselves in both their music and in the media, based on how they feel about the artist at that time. In Black Noise, sociologist Tricia Rose, now a part of Brown’s Africana Studies department, talks about the ability of rappers and their personas to articulate the ever-changing terms of Black marginality, in contexts like censorship in American society. She writes, “Even as rappers achieve what appears to be central status in commercial culture, they are far more vulnerable to censorship efforts than highly visible white rock artists…[They] experience the brunt of the plantationlike system by most artists in the music industry.” That same culture of censorship Rose highlighted in 1994 still echoes today, where Black women like Azealia face public backlash and erasure for speaking or behaving in ways that disrupt societal comfort.

This is most notable when considering Azealia’s incident involving Russell Crowe in 2016, where she was physically and verbally assaulted at a dinner in his LA hotel room. The general public was quick to dismiss Azealia’s testimony, deeming her unstable and overreactive, and even deserving of what happened to her, just because of her controversial opinions. Equating running your mouth and hurting your fingertips from typing so much to being deserving of abuse and mistreatment is a perfect example of how the general public treats and interacts with female celebrities. They are positioned in a complex dynamic with their audiences, where there is a need to act in ways that are deemed both socially acceptable and entertaining. If you deviate from one or both, the general public is quick to turn its back and rescind its support. This leaves artists with a need to please the masses, even if that means putting authenticity and reality on the back burner. Azealia has always been bad at this, leaving her subject to retaliation and mockery that can often cross the line of critique and turn into an inhumane force.

As of late, things have only gotten worse with Azealia. She spends her days spewing anti-Palestinian rhetoric and supporting Israel, even performing in Israel as recently as a few days before this article was written. She has become a professional ragebaiter who seeks to destroy the musical legacy that she could have cultivated. It enrages me to see how her views have turned more and more problematic over the years, which makes me question: why do I even bother to listen to her music anymore?

A classic case of separating the artist from the art could work for me. I’ve done it with artists like Roísín Murphy, an electronic music pioneer whose 2023 album Hit Parade dominated my playlists that entire year, after she made transphobic remarks against the use of puberty blockers on transgender children. However, Azealia’s case is a bit different because her music has become less than favorable. If you dive into her recent catalog, there’s not much to enjoy. Her latest official release, “Dilemma,” is a disappointing, sometimes laughable, attempt at UK grime that leaves you with the urge to cleanse your ears by playing anything from her 2012 EP, 1991. In that EP, her sleek delivery and clever wordplay, reminiscent of ballroom MCs, give you a taste of what could have been one of the most influential artists in modern pop culture. You cannot have damaging opinions and bad music in my book. At this point, I don’t see the point in showing her any grace. If she were to focus on her artistry instead of entangling herself with drama that has nothing to do with her—if she were to put that phone down—Azealia would be an unstoppable force in the music industry. Instead, she chooses to sell questionable soaps for her brand CheapyXo (known for not shipping their products even months after sale) and menacing Twitter by making disgusting remarks towards almost every minority group known to mankind.

I have now become indifferent to her mean-spirited opinions, her potential as an artist, and her feuds with other public figures. Whenever she appears in my life, whether it is in my Twitter feed or at the club, I enjoy and hate her. Some days, when her music plays at a friend’s house party, I can tolerate it; other days, I find the time to drag her in my public stories on Instagram. She has become a troubled, fleeting memory. A cheap perfume in your drawer that you see every day but choose not to use. A laugh. A case study for this article, instead of the “greatest female rapper alive.”