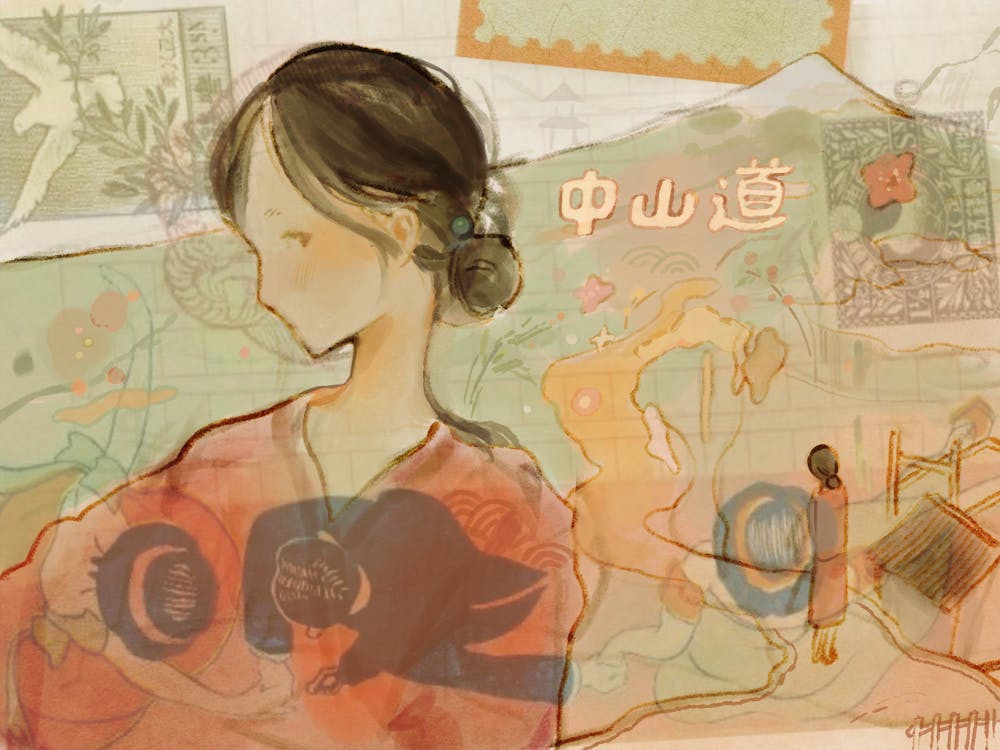

Upon seeing the RISD Museum’s Asian Art special exhibition “The Road Less Traveled - Edo’s Nakasendō” in my Urban Studies seminar, I was inspired. Featuring a plethora of works from my favorite ukiyo-e (Japanese woodblock print) artists Utagawa Hiroshige and Katsushika Hokusai, the beautiful landscapes of Japan reminded me of my deep love for Japanese landscape prints and the culture behind them.

This inspired me to embark on my own journey through the Nakasendō to explore the depths of the Japanese mountains and relive the road captured in these prints by the greatest ukiyo-e masters.

The Nakasendō was one of Japan’s main highways during the Edo period (1603-1868) that connected Edo (present-day Tokyo) and Kyoto. In contrast to the more heavily traveled Tōkaidō highway that ran along the eastern coast, the Nakasendō snaked inland across the central plains and highlands, covering terrain from rugged snow-covered mountains to expansive serene lakes. The route featured 69 post stations (juku) where travelers would stop to rest. On the trip my friend and I undertook in early summer, we traveled through some of the most famous post stations, stopping and staying the night in traditional inns, hiking and traveling during the day.

1. Kyoto 京都

Starting off in true Edo period fashion, we first arrived in Kyoto, which was the capital of Japan for over 1,000 years. Traveling to Arashiyama, I experienced the absolute beauty and tranquility of the Japanese mountains and forests. I visited Yusai-Tei Gallery, a Meiji-era building constructed roughly 150 years ago, where views of the Katsura River are adorned with works created by the host Yusai with a unique dyeing technique (yume-kôrozome). It is here that I experienced Kyoto’s beauty: its water, light, and serenity. Further into the mountain is the famous Arashiyama bamboo forest, where komorebi—a Japanese word that describes the kind of light in a forest where the rays of sun are filtered through the leaves of the trees—is fully understood.

During the night, we felt for the first time the pace of the countryside. While we ran up to the mountains during sunset, shops around us were still bustling with commerce; by dusk, the streets were dark and shops were closed.

Returning to Kyoto city, we explored the night views of Ninen-zaka, which featured small winding paths with shops on either side, leading to the hundreds of lanterns illuminating the night at Yasaka Shrine. Each lantern surrounding the dance stage bore the name of a local business in return for a donation.

The next morning, we traversed the most famous landmarks of Kyoto—Fushimi Inari Taisha and Kiyomizu temple. We climbed through thousands of vermilion torii gates leading into the wooded forest of the sacred Mount Inari. Afterwards, we climbed down to the base of Kiyomizu-dera’s main hall and arrived at the Otowa Waterfall to drink from one of the three separate streams of water that offer different types of auspiciousness.

2. Magome-juku 馬籠宿

Magome is where the journey really began. Taking the Shinkansen train to Nagoya, then transferring to Nakatsugawa, then a short taxi ride—we finally arrived at Magome-juku. Magome-juku is perhaps one of the areas of the Nakasendō that best conveys the look and feel of the Edo period, evoking its lively 400-year history. We stayed in a traditional ryokan (inn), tasted soba for lunch, and visited Toson Shimazaki Honjin museum. Honjin is an official inn for daimyo (feudal lords) on the Nakasendō. Born in Magome in 1872, Shimazaki is a highly regarded figure in Japanese literature. In his novel Yoakemae (Before the Dawn), he describes life in the area around the years of the Meiji Restoration, and it eventually became highly known in points on the Nakasendō.

3. Tsumago-juku 妻籠宿

Leaving Magome, we experienced the authentic hiking experience as we hiked to Tsumago, absorbing the scenery of gentle forest paths, tea houses, waterfalls, and wildlife. Not far outside Tsumago-juku, we stopped by a pair of famous waterfalls, Otake and Medaki. Named the “men’s falls” and “women’s falls,” these natural baths were used as separate bathing areas along the route.

Tsumago-juku, the 42nd station on the Nakasendō, is one of the most well-preserved Edo-period towns. Due to leaving Magome later than expected, by the time we got to Tsumago, everything was closed, the buses had stopped, and the streets were empty—yet, it was only around 5 p.m. Catching the last taxi waiting at the parking lot, we got to our ryokan, and luckily, the owner had two instant tonkatsu (pork cutlet) meals that he brought out for us.

After a restful night in a nearby ryokan with an onsen (public bathhouse), we explored the Okuya Waki-Honjin museum. The Waki-Honjin was the secondary inn of the post town, rebuilt in 1877 using Kiso hinoki cypress, a process that was only allowed after the prohibition of Five Sacred Trees of Kiso was abolished after Meiji Restoration in 1868. During the Edo period, the Kiso forests were controlled by the Tokugawa Shogunate (a feudal government), and cuttings were restricted to protect the forest until the Meiji Restoration, when these restrictions were lifted. It was said that the Meiji Emperor had come to this honjin for only 30 minutes, but they had made specifically for him a whole room and even Western-style bathrooms that ended up never being used. The Tsumago Honjin museum also offered numerous insights into the Kiso Valley’s history, especially the style of logging and the methods of harnessing hydroelectricity by utilizing unique geographical features.

4. Kiso-Fukushima 木曽福島

Kiso-Fukushima was a quiet and peaceful mountainous town that we arrived at by way of Nagiso station. Kiso-Fukushima was one of four security check points along the Nakasendō, flourishing as a political and economic center in the Kiso Valley. We explored Yamamura Daikan Yashiki, a samurai residence housing the local magistrate and gatekeeper of the Kiso-Fukushima Sekisho (checkpoint). The Yamamura family ruled the Kiso Valley throughout the Edo period as samurai, and their residence also appeared in Shimazaki Toson’s Yoakemae, showing how the stations were all connected in different ways.

Afterwards, we visited the Kozenji Temple, with its magnificent kanuntei (rock garden)—the most spacious dry landscape garden in Asia. With a view of the Kiso Mountains and Kiso River, it showed imagery of a mountain floating on a sea of clouds. The zen garden with stones arranged in groups of three, five, and seven portrayed a sense of movement in stillness. Finally, the Fukushima Sekisho marks the halfway point along the Nakasendō, with the Fukushima Seki representing the important checkpoint. It was here that officials checked travel and gun permits.

5. Narai-juku 奈良井宿

After a quick train ride to Narai station, we finally arrived at our last station to explore: Narai-juku, known as “Narai of a Thousand Houses.” Narai-juku is one of the longest stations, with the main street stretching over a kilometer, and also one of the wealthiest. Today, it is one of the most commercialized and popular destinations along the Nakasendō. We also visited historic temples and shrines just off the main street. Standing on top of Kiso-no-Ohashi Bridge, we viewed the Kiso River one last time as we concluded our journey, following the guidance of the river, and traversing the mountains of Edo-period Japan.

6. Tokyo 東京

After five days in the mountains, we concluded the experience in the true fashion of the Edo travellers: taking the train back to Tokyo, back to the city, and back into the present day.