I have always loved the way that cubes of chicken stock dissolve into hot broth. My grandmother first taught me how to make chicken noodle soup when I couldn’t even see over the top of the stove. She sat me down on the counter next to the pot, explaining each ingredient as my grandfather helped chop carrots and celery. I swung my legs; I wore pigtails; I felt the warm steam on my cheeks.

Before every holiday, my grandmother makes hundreds of cookies and hand-delivers them to members of her universe: the kids on her block, my uncle’s friends from high school, people who worked with my grandfather, her electrician. For her, making cookies maintains connection, keeps people close. This applies to me and my cousins too, because before each Easter and Christmas, no matter how much we’ve grown up or how far we’ve moved away, we come home and dedicate a Sunday to decorating sugar cookies with her.

Last winter, shortly after the Christmas cookies were mass-distributed, my grandmother and I tackled another Sicilian tradition: arancini. To make arancini, you have to dip each rice ball in egg, flour, and breadcrumbs before frying. The process is incredibly messy, and you end up with egg and flour and breadcrumbs stuck all up under your fingernails. As we dropped each rice ball into the pot, I felt so closely intertwined with the food (which was in the crevices of my cuticles), with my grandmother (who was guiding each step of the recipe like she always has), and my grandfather—who passed away years ago but would be so happy to know we were still making things together.

***

My mom has always taught me to notice beauty everywhere. Growing up, we spent our favorite days together picking out new towns to explore, pointing out every lovely detail. Even when I’m far from home, we send each other pictures of flowers and of the sky, always sharing the very best moments with each other.

One morning last summer, she leads me on a new adventure around Ocean Grove, New Jersey. We pass gardens and front porches with swings and a fig tree and a wishing fountain before finally stopping in front of a mailbox bolted to the side of a house. “TAKE ART / LEAVE ART / SHARE ART,” the box reads, painted bright blue and red, adorned with a star-shaped mosaic. The box is completely filled with artwork contributed by community members—drawings, collages, stickers, jewelry, pottery.

A piece on the shelf catches my eye: a dish in the shape of an oyster shell, shimmering and painted in mottled blues. I am hesitant to take anything from this box without something to contribute back, but my mom reminds me that this art is meant to be shared. And besides, she’ll leave a drawing there tomorrow.

Now, whenever I look at the dish, I think of the stranger back in New Jersey who made it with such care, diligence, and wonder, and decided to pass it on, leaving it up to the universe to decide who got it next. Parting with something textured by their fingerprints, all for the sake of the community and the unknown. As I trace over the imprints of their fingers in the clay, I feel tied to something much larger than myself. I feel tied to my mom, too, who is the reason I seek out art in the first place, and the reason I care so much.

***

A few years ago, on a whim, I picked up a cross-stitch kit at the counter of a record store. I had no experience with any kind of needle arts, but I was feeling disconnected and I wanted something grounding—something to do with my hands. As I worked on the craft all weekend, fingers stumbling through each stitch, I fell in love with the intense focus and patient concentration of creation, the profound appreciation for and sense of kinship with whatever I had in my hands.

Ever since, crafts have become my love language. By creating things for the people who matter to me, I hold my love in my palms, immortalize it into something tangible and lasting. Over the years, scrapbooks and embroidery have become my favorite gifts to give.

Last November, when Kate and I had only just started dating, she gifted me a handmade pair of beaded earrings, periwinkle and sage and silver and forest green. My favorite colors, and a perfect match to the rest of my jewelry. To receive something handmade as a gift, I understood then, is to be known.

Many months later, I made her a necklace, wielding mineral oil, wire, and pliers to turn the colorful rocks I collected into pendants. Although we live states apart, the distance isn’t so far when we wear the pieces we made for each other. When I wear her earrings, I know that she selected each bead with intention, consideration, and warmth. And I am honored that she found these beads beautiful, and that they made her think of me.

***

Braiding Sweetgrass by Robin Wall Kimmerer is Kate’s favorite book, so I spent all summer reading it, taking weeks between chapters to digest and embody each story. Braiding Sweetgrass is an unparalleled work of art, a love letter to the natural world and a call for us to reshape our relationship with the earth, with each other. Kimmerer synthesizes Indigenous ecological knowledge with her academic background as a botanist, urging us to learn from—and act as stewards for—our environment and our community.

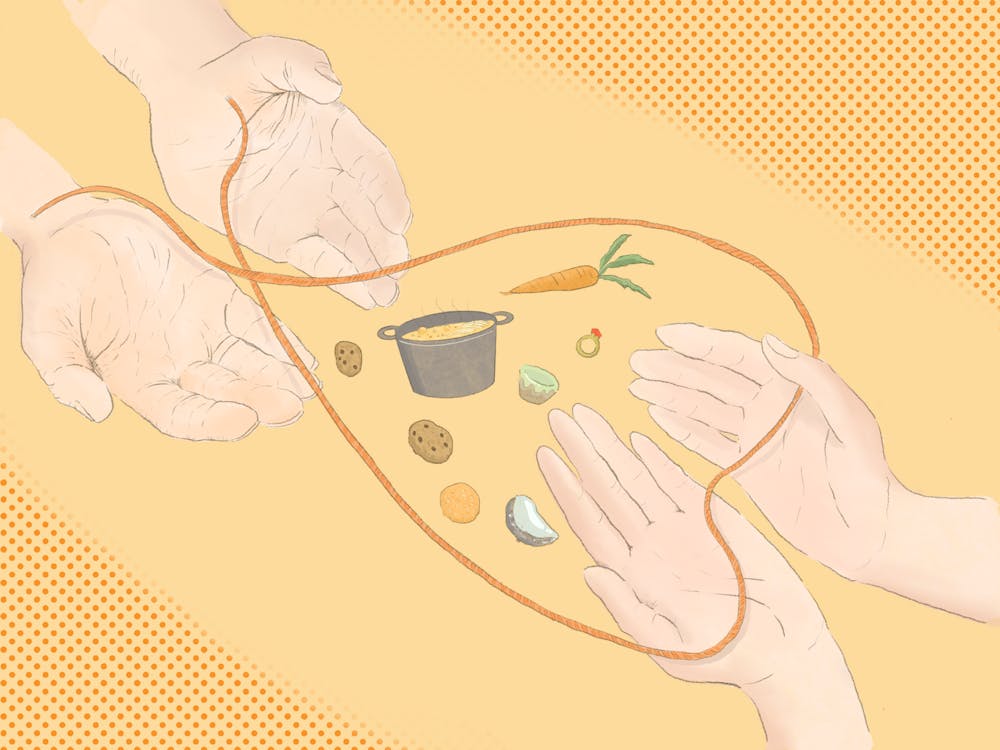

In one essay entitled “The Gift of Strawberries,” Kimmerer explains that in her tradition, the “value of [a] gift [is] based in reciprocity,” as there is a mutual understanding that everything that is given will ultimately circulate back. To Kimmerer, “The essence of the gift is that it creates a set of relationships.”

This chapter moved me deeply, and I think of it often as I move through the world. I especially felt its impact when I first encountered the art library in Ocean Grove, as Kimmerer emphasizes the importance of giving gifts as the currency of community. When we make and we pass forward, there is an implicit understanding of reciprocity, trusting that we take care of each other and are taken care of in return. I think of this when my friends bring a homemade sign to cheer me on at my field hockey game. I think of this when I drop off fresh arancini on my uncle’s front porch. I think of this when a stranger compliments the t-shirt I embroidered. I think of this when I try to learn my girlfriend’s favorite songs on the guitar.

***

Years ago, Nadia and I made Soleena a scrapbook for her birthday—that scrapbook sits on the coffee table of the home we all now share with Kaiolena and Sophia. We cook together, we bake for each other, banana bread, apple crisp. I make bracelets to bring back to the art library. And I work on my new embroidery project: a tote bag stitched over with designs drawn by the people I love. A collage of care immortalized with thread. My greatest hope for this tote bag is that it is dynamic, that one day I will have to cram designs into its margins, but even in its early stages it conveys the fullness that I feel.

At the end of “The Gift of Strawberries,” Kimmerer urges us to embrace “a gift economy,” as it “opens the way to living in gratitude and amazement at the richness and generosity of the world… When all the world is a gift in motion, how wealthy we become.”

I adore that phrase: “a gift in motion.” How deeply I hope we never stop creating for each other. How deeply I hope we always carry love in our hands.