Recently, there has been a curious, serendipitous pattern in my media space. In a week, I encountered three works united by a common idea—the Law of Talion, which may be more familiar to you as the principle: “an eye for an eye, a tooth for a tooth.” These pieces included the Spanish story “Ley del Talión” by Max Aub, the movie The Killing of a Sacred Deer by Yorgos Lanthimos, and the song “Equivalently” by the alternative Russian rock group Papin Olympos. Pretty eclectic, don’t you think?

Revenge has been around for quite some time—Hamlet, Odysseus, Oedipus Rex. The original phrasing of the law dates back to the Bible: Fracture for fracture, eye for eye, tooth for tooth; whatever injury he has given a person shall be given to him (Leviticus 24:20). In the New Testament, Christ reorients this principle for personal actions: Ye have heard that it was said, An eye for an eye, and a tooth for a tooth. But I say unto you, Resist not evil. But whoever slaps you on the right cheek, turn to the other cheek also (Matthew 5:38-39).

Everything works as a fair trade until we get to harm; in that case, the rules change. Instead of multiplying evil, we need to put an end to it through the power of mercy and non-retaliation.

The version of the idiom that lingers in the pieces I’ve listed is the Old Testament one, or the “retributive principle.” For the authors of the works in question, the principle provides solace—a promise of justice, relief, redemption. To start, look at Aub’s story “Ley del Talión,” which I have translated from Spanish into English:

—I didn't do it on purpose.

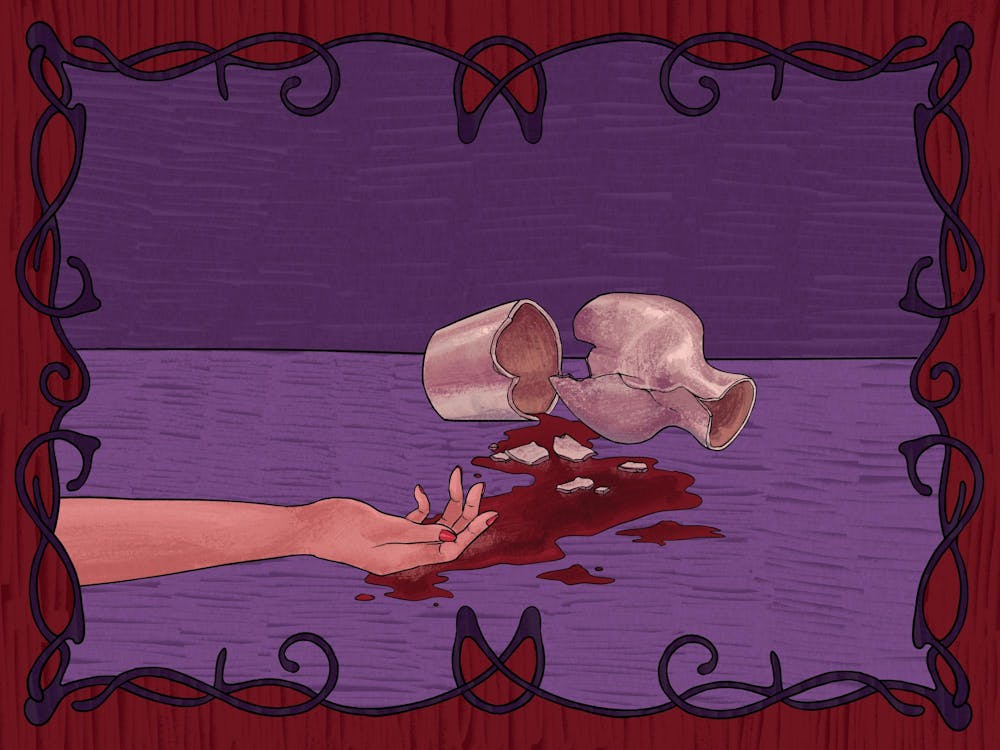

That's all that occurred to that imbecile to repeat in front of the shattered jar. And it was my saintly mother's, may she be glorified! I smashed her to pieces. I swear I didn't think, not even for a moment, of the law of Talion. She was stronger than me. I didn't do it on purpose either.

END

The narrator explains how he cuts a woman into pieces because she broke his mom’s favorite jar, suggesting this punishment was only fair. The mirroring language to break a jug into pieces/a man to pieces is chilling, as it innocently plays with the idea of a life being exchanged for a life. The striking brevity of the story accentuates the draconian calculations in the mathematics of revenge. The naïveté of I didn’t do it on purpose being equal for both scenarios—breaking a jar and violently murdering a person—suggests an eerie moral trade-off, where justice is regarded through a curious lens…Why should we forgive people, if they truly hurt us?

As for The Killing of a Sacred Deer, it’s an absurdist psychological thriller directed by Yorgos Lanthimos that explores the idea of a universal equilibrium, where no mistakes go unnoticed. A cardiac surgeon introduces his family to a teenage boy, Martin, who inflicts a curse on them because they deserve it (watch the movie to find out the reason). But why is there comfort in the thought of retribution? Why does restoring balance by multiplying evil seem fair to us? When talking about the “eye for an eye” principle, Martin says this: I don't know how fair what's happening is. But you know, in my opinion, it's the only thing that comes close to justice. He thinks that only by responding good to good and evil to evil can the fragile balance be restored—if not pure justice, then at least some functional model of it.

Finally, in “Equivalently,” we hear such phrases as Someday everyone will pay their bills / Mercury, that flowed down those cheeks, will return as gold / Wait just a little bit—time will put everything in its place / Someday—that's how the boomerang returns. The melody also mirrors the motive of an upcoming Judgement Day: the refrain of “Equivalently” circles back to the note C, and the bridge (quoted above) is recited a cappella, almost like a manifesto. The lead singer’s voice is youthful, even boyish, which amplifies the uncanny maturity of the lyrics.

Funny how a seemingly unconnected 20th century Mexican-Spanish novelist, a modern arthouse Greek filmmaker, and an alt-rock Russian teenage band keep circling around the same bloody rulebook. Why do we gravitate to this primitive, rigid, even barbaric idea that takes us back to the birth of legal regulation, back to the Twelve Tables in ancient Rome and the Laws of Hammurabi? Or perhaps it is not a craving for violence and retribution at all, but a natural thirst for justice. What if Talion’s law is real justice, where the scales are equal and the punishment perfectly fits the crime?

Actually, Talion's Law inspired a whole philosophical and legal movement, retributivism. Modern systems of justice blend the law with utilitarian goals, such as simultaneously establishing stricter sentencing guidelines for serious crimes and implementing parole for rehabilitation. The practical part of this mix echoes one of the laws in Hobbes’s Leviathan: In revenges, men look not at the greatness of the evil past, but at the greatness of the good to follow. In other words, revenge is used not for vengeance, but to establish a social order. However, a certain C.S. Lewis would disagree with this overly forward-looking viewpoint. He was a loyal fan of retributivism—in his Humanitarian Theory Of Punishment, he claimed that “the concept of Desert is the only connecting link between punishment and justice.” Lewis critiqued the rehabilitative system of punishment, stating that prioritizing the future serves the purposes of deterrence more than it does the purposes of justice. The debate around retributivism today is #notdead (Lewis would be glad).

It seems just about time to address another relevant and vastly popular idea: karma. Mired in its pop-cultural definition, we forget karma is not just a petty human payback; in Buddhism, it is regarded as an autonomous law, which operates merely on human actions and their effects. There isn’t an omniscient ruling agency that assigns punishments and rewards; karma is simply a fair game, where every action creates a corresponding reaction, which manifests across lifetimes. Karma is an objective responsibility, even sometimes referred to as a “causal mechanism.” Thus, both karma and our beloved Talion's law can be seen not only as a selfish attempt to make another “pay the price,” but also as a cosmic longing for justice and order, or a universal principle—something bigger than animalistic drive for revenge.

However, there is indeed a biological reason that makes retribution tempting. From a neuroscientific point of view, revenge is sweet. In a study where the participants had a chance to punish the impostor in a game, there was significant arousal in the activity of the dorsal striatum, which is associated with processing rewards (yes, cocaine and nicotine included). Revenge does, however, have you wrapped around its finger: the sense of satisfaction is often short-lived. “Punishers” didn’t release their aggression. On the contrary, they felt more resentment and anger than those who opted for forgiveness. In other words, the temporary relief after vengeance is similar to the one associated with addiction. It feels ecstatic at first, until the high wears off.

Despite this neurochemical trap, the ancient Talion's law remains relevant—perhaps because our attraction to pure mathematical equality and retributive justice has not disappeared. I believe that there is something in human nature that simply does not allow us to put up with injustice, something more unfathomable than the striatum activity or the lyrics of a Russian teenage rock song. And the belief that someone out there is keeping score, that it’s just a matter of time before the scales will swing back into place, is our consolation prize. To be honest, this placebo pill works for me—I would certainly love to see the universe put everything in its place and give my enemies their just deserts.

But let’s face the brutal truth: revenge, no matter how meticulously calculated, can never ease the underlying pain. Revenge is an illusion of closure, of reclaiming power, of punishment. I don’t believe violence is a driving force for retaliation—it is rather a consequence. Revenge would need a deeper-rooted motif.

Revenge is driven by grief.

Grief is blinding and maddening, be it caused by a lenient punishment for the murderer of your child or the absence of repercussions for surgical misconduct. Vengeance is a way to mobilize the destructive passivity of grief, reverse the pain, and throw the boomerang back. The barbarism of vengeance comes from desperation and helplessness, but it’s just a cover-up for a wound: deep down, we know nothing can fix the past, not cruelty, nor equal suffering.

So next time you decide between turning your other cheek and punching back, pause and ask yourself—if revenge is grief, will fighting back even make a difference?