I rarely speak my native language at Brown. When I come back to my dorm and think in English—out of habit—I feel pathetic. It’s not because I don’t enjoy speaking it—it's this shift that reminds me of the performativity that underlies daily conversations. I sit on the floor and catch myself using generic filler phrases that are commonly used for comforting and supporting others. You’ve got this. You’re doing great.

And then I wonder why I don’t feel any better.

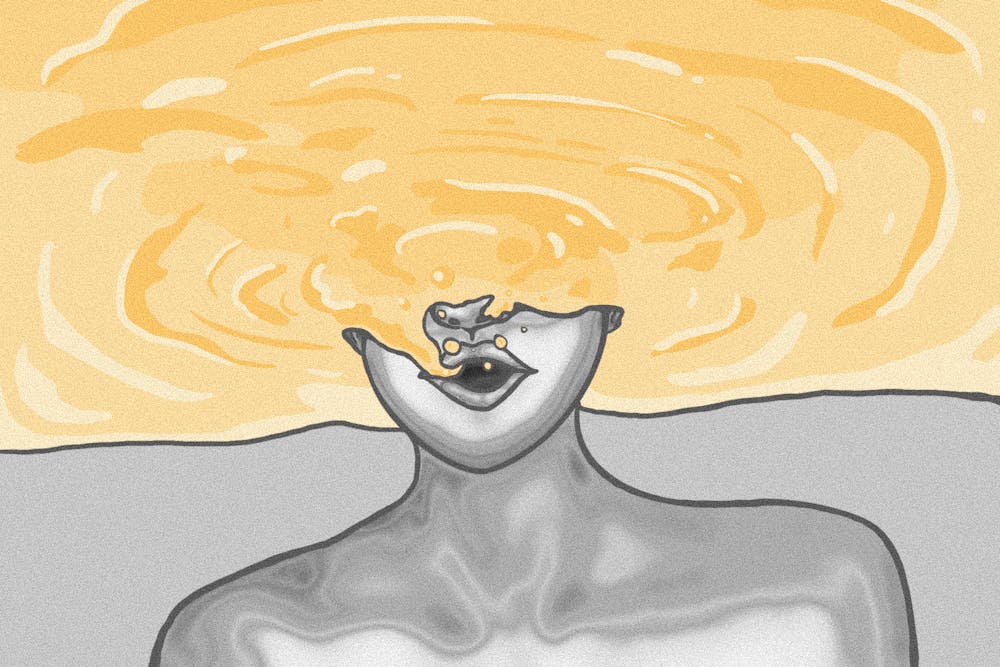

English has a delightful flow. Its transitions are seamless and smooth—it envelops you like fog in the mountains; when I speak, I envision a river of milk and honey that lulls and carries me far away. But the milk is murky. You can get away with just using a sequence of socially-beloved phrases, stretching out in a meaningless chain, one after another. When I use them, it’s as if I have given up my sense of autonomy and engineered my communication to be traditional, tried and tested rather than tailored to this particular situation. The range of situations where expressions sparkle with feigned joy (wow!! no way OMG!! that’s amazing!!!!!!!!!) could include either a wedding or a well-seasoned salad, a decision to S/NC a class, or… actually, to not S/NC it as well.

Russian snaps me back into reality. So do Spanish, French, and Portuguese. In those languages, there is no secure scenario to follow. Speaking Russian is riskier than sticking to the dialogue templates in English, but much more raw and rewarding. When I hang out with my Russian-speaking friends on campus, I feel exposed, as if the eggshell that I’ve been carefully hiding behind this whole time is cracking and falling down. Here I am in front of them—naked, raw, unrefined.

Neuroscientifically, it's less taxing to describe emotionally charged experiences in a foreign language. Deep autobiographical memories and experiences are rooted in your native language. To talk about them in a foreign language, we don’t just rely on emotional processing, but on many other cognitive functions, which dampen the emotional reaction. That’s why I can convince myself in English that everything is phenomenal and that ‘you’ve got it, girl,’ but when I stare at myself in the mirror and manually switch my thoughts to Russian, the same words affect me much more strongly.

Paradoxically, speaking your native language to yourself and a foreign one to others lead to almost the same degree of embarrassment. When I speak Russian to myself, I can’t hide behind a barricade of fake consolations and luscious compliments. It’s a language in which my бабушка makes brutally honest comments about my housekeeping skills, in which my папа corrects my posture, and my мама psychoanalyzes my romantic interests. It’s also the language that Dovlatov spoke and never sugarcoated. There is no place for hypocrisy in Russian, or The Native Language in general. That’s where vulnerability comes from—facing the “quivering creature” you are when no one is there to smile, nod, and bounce back with a comfortable anecdote.

As for the embarrassment when speaking a foreign language, we all know how it feels to be paralyzed when the all-mighty native speaker looks you up and down as you try to mumble, “I’d love to visit Brazil.” The part that hurts the most is how reassuring and excited they seem when they tell you, ‘You speak so well!’, which only further confirms how awkward you sound. It feels like the extent of your non-belonging is so huge that it relieves them—you’ll never be at their level, so why not grant you a condescending remark? This embarrassment you feel is also a kind of rebellion—confronting your own pride and arrogance in even daring to speak their tongue.

Are you ready to sacrifice your confidence to melt into a new version of yourself? How far will you go, knowing that, for a long time, this version will be a reductionist shadow of your personality? How hard will you push yourself to reinvent the way you think about grammar, intonation, and pacing? How much will you change, stepping so far away from yourself, and which aspects will remain untouched by the transformation?

You know what the worst aspect of the language barrier was when I moved to the US? Humor. Sarcasm used to be my main means of communication, and I was effortless with my jokes in Russian. I was absolutely paralyzed when my toolbox of shared cultural code, experiences, and wordplay disappeared. That first week at Brown, when not only the characters and objects around me were new, but even my own words felt alien, extraneous, and clumsy, was a distressing yet adventurous linguistic expedition. I made many new friends, and one of them was the English language. It never replaced Russian, but it offered me its own treats, like slang, puns, and proverbs. I didn’t betray myself by switching to a different mode of communication; I architected a symbiotic system where every new language benefited and enriched my identity.

But honestly, language in its essence is pure embarrassment. Any of your ideas, when they lose their spiritual and intangible nature, become flawed and then easily critiqued. And to be eloquent enough in at least one language takes dedication and tedious revision. Maybe that’s why people tend to slip back into familiar conversation templates. There is no need to make any risky decisions on how to describe your summer or make a person feel better.

In order to succeed in a language, be it foreign or native, it’s crucial to know why you speak. Is it to maintain a socially acceptable distance, to keep others away from your true persona, masking it with empty epithets or soulless interjections—or do you actually want to foster a connection and put yourself at the risk of being judged for what you believe?

I invite you to break free of the automatic mode of perception and start thinking, start speaking, for yourself. Maybe that coat is not AWESOME—maybe it’s the fabric, or the pockets, or the silhouette that you’d rather point out. Or maybe you don’t even like it that much. Critical thinking is not just a tool for the classroom, but also a way to challenge yourself and break the vicious cycle of conformism and performativity.

We have control over the word choices we make. Don’t hide behind them; use language to be seen, and you will soon feel addicted to expressing what’s on your mind, and not the one of the collective consciousness. Take risks, stay sexy.