content warnings: description of mass suicide, mentions of rape

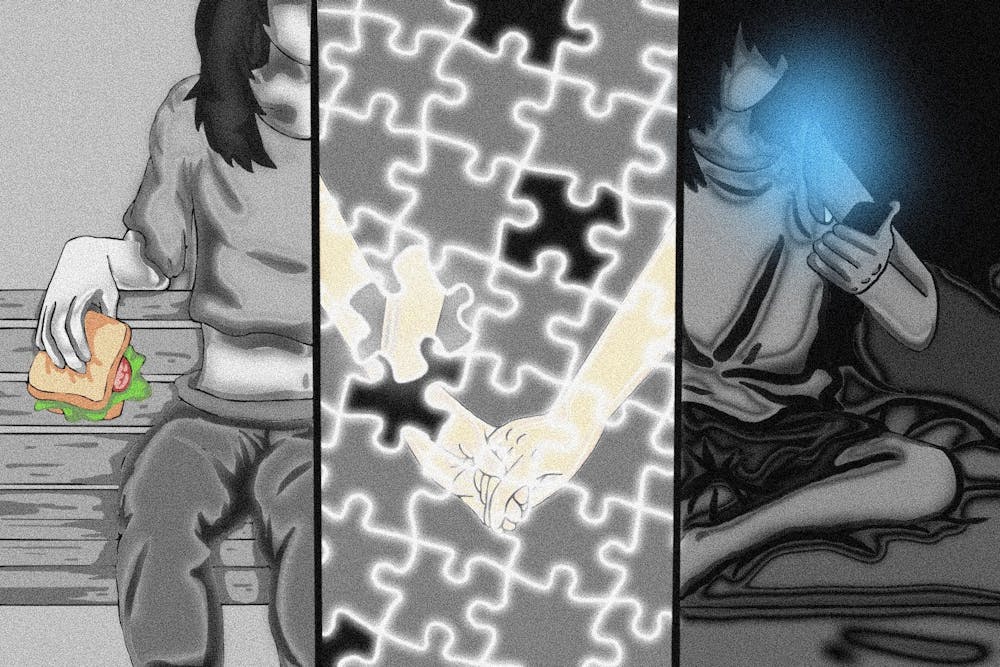

Fifteen years from now, when I am thirty-six, I wonder if I will still be thinking about utopia. If, as Annie Dillard says, how we spend our days is how we spend our lives, my life will not be spent writing, but imagining. Utopian humanism swells in me while sitting at my desk, tapping its wooden surface with my nails; and while turtling along the Quiet Green, a melting strawberry-banana smoothie wetting my hand; or even while I let my ass drowse against a chair in a class in Sayles Hall, waiting for the ceiling to collapse into puzzle pieces that I can slide back together. It seems that everywhere I go, I wait for utopia to come. Perhaps a better explanation is that I wait for utopia to come together.

*

I do not see utopia as all-consuming, cluttering my consciousness like used cardboard boxes. Utopia is not necessarily a daydream, even if I dream it, but rather a comfort, an attachment I believe in to keep myself going–the difference being that I recognize utopia is out of reach, because by definition it is unreachable, and somehow that dynamic atomizes it into something material, something that feels close to me.

*

I continue reading confessional poetry and dystopian news articles past my bedtime. I consume what appears to be the collapse of most public institutions: Brown’s pausing of PhD cohorts in many humanities disciplines; the collapse of the F.D.A. under RFK; and the defunding of public media organizations like NPR come to mind. I write in my journal, concerned by what these changes mean for the ways we can conceptualize and imagine better worlds.

*

What are my utopias?

For one, I am a college student, meaning I inhabit the bubble of all bubbles: the college campus, the insularity of its social and political sphere, and seeming liminality (even as it is fleeting). My muscles loosen up at the thought. In this vision, there is no outside world. I attend university to hone my craft, learn about the history of art and literature, and nibble on Caprese sandwiches with dear friends on sunny, peach-orange days. Some days, I feel so close to reaching this utopia that I wonder if it could be real.

The farthest dreams are those that enchant me more. I long for a world following the tenets of sympathy and spiritual equality, in the words of the late poet Alice Notley, in the lineage of the second generation of the New York School of poets. There is, too, the utopia of the post-grad city, gliding on the 1 train downtown, clutching a bottle of Chardonnay in one hand and a romantic partner in the other. But most of all, I no longer want to exist between two worlds of cis and trans living. I envision a world free of the corruption and emotional statelessness of the cisheteronormative outerworld and the hopelessness of the trans underground. I close my eyes and see myself in harmony with all the other trans women of the world, in sisterhood, those who are not American especially. There are no borders and there is no gender violence, only escape.

*

I apologize. I realize now it is impossible to pinpoint these utopias; any such attempt would be incomplete. How can I know I want something without having lived it?

That is to say: How do I know if something is a utopia?

*

Sometimes, I witness utopia's opposite, something so vile and true that it forces me to reconsider the very terms of utopian thinking. Not just what I long for, but how I imagine getting there, destabilized into its black-hole-galaxy: the fantasy that there is collectivity in suffering, that what binds us might also be what kills us.

I am an American trans woman. Though the U.S. is descending into an anti-trans frenzy, I still have safety and immense privilege compared to trans women in much of the world, and my imagination for responding to violence has been shaped by that safety.

*

This month, I watched something that forced me to reckon with a different kind of collective action, one I could never have imagined from my position of relative safety. It happened to trans women I will never meet, in a city I've never been to.

24 trans women tried to commit mass suicide in Indore, India, after another trans woman in their city was raped. Two men had approached the woman, pretending to be journalists. When she called them out on their charade, they blackmailed her, dragged her to a nearby building, and assaulted her.

There is a video.

Through the grainy film of my phone screen, on Instagram reels, no less, I watch two dozen women sprint through busy streets, stampeding toward a house. In the close-quartered, locked home, the women consume phenyl, a floor cleaner. Though the media organization chose to blur the footage, the women’s coughs line the static audio, sickeningly. With time, I watch the women deflate, in the same way the advertising balloons do. Some clap their hands together, seemingly calling to some greater force. G-d, each other, the camera—there is no way to know. Half of them sprawl out on the floor, mouths agape. The footage resembles a stop-motion film, fights erupting in the streets between the remaining women who can still stand and police officers, chests puffed out. The brightness of ambulance cars jackknifing my vision. Footage of feet and painted toes tied to blue hospital beds.

I heart the video.

*

I try to imagine the person I was before I saw the video. I scroll through my mutual friends who have liked or reposted the video, most of whom are trans girls my age living in New York City.

*

(I have a fantasy that I live with them, any and all of these trans girls, waking up in a communal New York City apartment, drowning in linen sheets, tiptoeing through south-facing windows, where we will make banana bread and hard-boiled eggs for breakfast.)

*

I call my mom; she is busy, on the phone with a relative. I turn my phone off and under my covers, my body heats like a kettle. Am I really that unable to hold their attempted deaths without immediately creating a fantasy? Why is my response to immense anger numbness, followed by a return to my utopian thinking? How American of me, how self-centered. What an awful thing: to absorb their despair before refusing it, tipping it like a dunk tank onto the street, where it will splatter in liquid form.

*

This is my second apology. What are the ways in which I have come to conceptualize my dystopias?

*

I am living my dystopia, in that I am directly impacted by the political, and subsequent cultural, shift to the right in day-to-day life, in ways that others may be able to turn a blind eye to. I am living my dystopia, in that I am quick to blame my peers, who are not at fault for this environment, and who, too, were born into it without consent. I am living my dystopia, in that the powers that be are stronger if I give in to this isolation, believe in seclusion, squeeze the blade of guilt so compact until my soft palms bleed, the blood trailing away, snakelike.

*

Douglas Crimp writes in 1989: "There is no question but that we must fight the unspeakable violence we incur from the society in which we find ourselves. But if we understand that violence is able to reap its horrible rewards through the very psychic mechanisms that make us part of this society, then we may also be able to recognize—along with our rage—our terror, our guilt, and our profound sadness. Militancy, of course, then, but mourning too: mourning and militancy."

*

I am living my dystopia, in that the trans girls are not really my friends. I will never meet most of them. Our connections are just as fragmented as the digital networks that link us.

*

The women of Indore chose a different exit than I dream of. They manifested their anger and rage into reality. They attempted to create their own utopia, or rather a response to its opposite, an ultimate failure so impossible to hold in my mind that I can only understand it through the grainy footage on my phone.

*

Third apology, but this time I will not apologize.

*

What are the ways I have stopped dreaming?

What are the ways my classmates have stopped dreaming?

What are the ways you have stopped dreaming?

*

And what, then, of my classmates?

There are some who watch and heart videos, if only to quell the circular pounding of their own organs. Others do not watch at all, which they consider emotionally moral or politically necessary, depending on who you speak to. A few strut along the Main Green with messenger bags flapping against their baggy pants, speaking about how we are just so fucking fucked. They scare me, only because they are truthful, which means they have learned not to believe in utopia. What I fear most are those with their Blue Room feta cheese salads who are exhausted into silence.

*

I go back to my poetry notebook, where I try to make sense of how my day-to-day life has shifted. My eyes scrutinize the pages, and I scribble themes, little notes I imagine looking back on someday. A few of my gay guy friends are talking about wanting to give up and try out women, and they say it as a joke, but there's something weak in their giggles. Bunches of Lit Bros sit in the Rock, sliding copies of Nietzsche and post-modern novels like hockey pucks across tables, finding warmth in intellectual nihilism. It feels like everyone is scared to be even the smallest bit subversive.

*

Whereas some of my classmates continue to try to forge their own utopias in spite of the dystopia, I wonder how they recreate dystopia in the process. Does cataloguing my classmates dilute my own complicity?

*

WOKE IS UNDEAD AT BROWN, a sign on a pole by the Ratty declares, in neon pink text, in the final weeks of October. I do not know who put it up, but they have requested I COME CELEBRATE DURING HALLOWEEKEND.

*

In the rain, the sign saturates, but remains nailed to the utility pole.

*

I FaceTime a friend from LA, a self-described transsexual. On the green, I scoop chickpeas into my mouth, chewing. Through my phone screen, I see her face while behind me a machine promises to send a message to my future self.

*

I am mourning, but there has not been a militancy, not yet, not yet, not in me or at Brown, where everything supposedly is paradise. In class, I watch a video from 1992 of ACT UP activists throwing the ashes of those who died of AIDS on the White House lawn.

And then I walk through the No Kings Rally during Family Weekend, passing signs held mostly by Gen Xers yelling, THIS IS WHAT DEMOCRACY LOOKS LIKE.

*

I hunch over in my bed, scribbling abstract language in my notebook—air & dust & particles, still. A breath, hoping the nonsense might manifest as coherence. I hear from a friend who does laps at the campus pool, freestyle, backstroke, hundreds of meters, swim cap permanently smelling of chlorine. They say the routine is nice. It does something for them.

Tourmaline, speaking about the trans elder Miss Major, who recently passed away, says: “As Miss Major says, sometimes you can’t go outside. Maybe there’s a heightened presence of people who will harass you or arrest you. Sometimes you just don’t have the energy to. But can you find pleasure and luxury in a cold drink of water?”

Their utopia is the pool. I am glad to know utopia still exists.

*

At night, I pour myself valerian tea and knock myself out. In my dreams, language still hums, and I hear sentences, bits that enliven me, even while unconscious. And then I have breakfast with a friend, and I stuff a croissant in my mouth, and we hug each other and laugh about frivolous joys.

Maybe the possibilities are not in the future or the present or the past, but something in between, a place I can’t yet name or fit in the arc of history, if only because this cultural moment feels so shocking it registers as surreal.

*

On an algae-green towel resting atop sand at RISD beach in Barrington, I let the sun smooth from my toes to my scalp. Soon after, in the water, waist-deep, a friend takes my hand, our thumbs brushing circles against each other’s palms.

*

And what of the women of Indore? How can we honor them?