“哥哥的黄金时代也就我们黄金的时代...后来我知道,我们的时代纯属偶然”

His golden era was our golden era…Later, I understood that our era was purely coincidental.

Ng Chun-hung, Hong Kong Economic Journal (August 17, 2004)

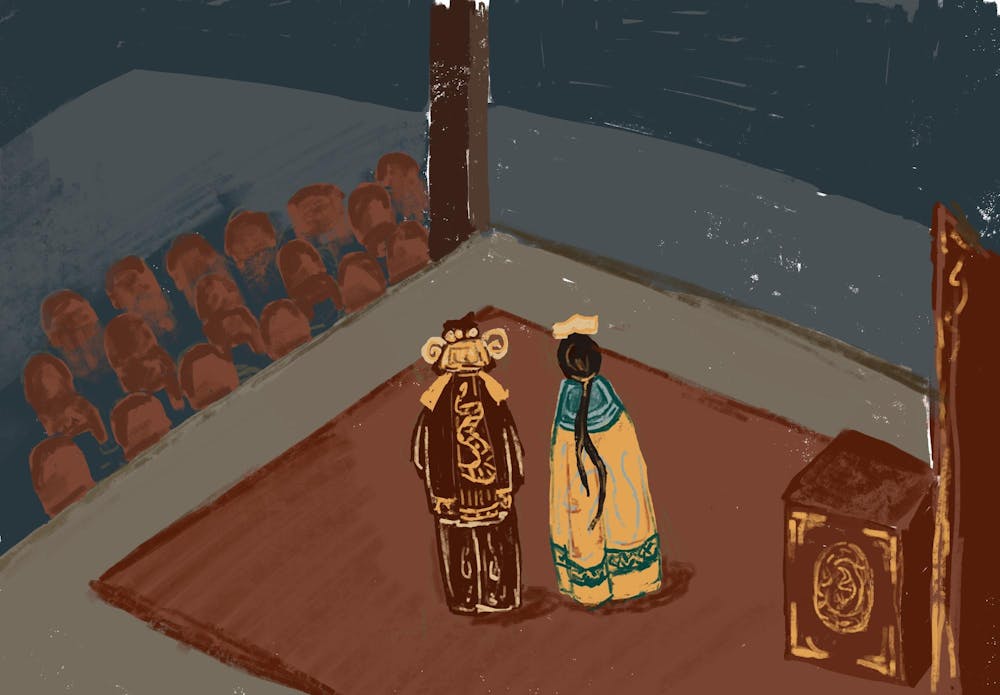

Farewell My Concubine begins at the end: In its opening shot, two figures stand in full opera dress in the middle of an empty theater, bathed in dusty light. A disembodied voice calls out from off-screen, It’s been over 20 years since you two have performed together, right? One of the performers answers falteringly, Twenty-two. And it’s been 11 years since we last saw each other. The voice follows up, It’s the fault of the Gang of Four, isn’t it? A lengthy silence, and then the answer, Isn’t everything?

The voice exits, and a harsh blue spotlight settles on the two performers center stage. A single drum rattles and they begin their last rehearsal.

Farewell My Concubine is set against the turbulent history and political upheaval of 20th-century China. It tells the five-decade-long epic of two men who meet in childhood at a Beijing opera training school and have their fates inseparably intertwined throughout their lives. Douzi is abandoned at the opera troupe as a timid young boy and finds kindness in the bigger and brasher Shitou, the boys’ de facto leader, who shields Douzi from their masters’ cruelties and becomes his closest friend—and later, unrequited love interest. As they grow up, Douzi is trained to play dan (female) roles while Shitou is trained in jing (rough male hero) roles. In adulthood, they are famous and perform under stage names: Douzi has become “Cheng Dieyi” and Shitou “Duan Xiaolou.” In a blur of fiction and reality, their stage lives and their personal lives shift as political power over China changes hands rapidly—the warlords of the 1920s give way to Japanese occupiers, then comes a brief period of Kuomintang control in the 1940s, and finally the grip of the People’s Republic.

Released in 1993, Farewell entered theaters on the precipice of another historical power shift. On the horizon—just four years away—is a looming expiration date. On July 1, 1997, the United Kingdom is set to hand over sovereignty of Hong Kong back to China, transferring Hong Kong from one imperial power to another.

In the context of its trans-Chinese influences, Farewell is thoroughly bizarre. With film markets in mainland China and Taiwan opening up after significant economic and political shifts, and the prominence of Hong Kong artists rising throughout the ’80s and ’90s, Farewell was made just in time to experiment with a bold new co-production model between mainland China, Taiwan, and Hong Kong. It was produced and directed by a mainland studio and director, financially backed by a Hong Kong subsidiary of a Taiwanese investment group, and cast in the lead role of Cheng Dieyi was Hong Kong’s biggest star of the 1990s—Leslie Cheung.

Cheung rose to prominence as a pioneer of Cantopop in the ’80s. As a performer, he was known for his queer and androgynous aesthetic and stage presence. Like over 200,000 other Hong Kongers in the decade leading up to the 1997 handover, Cheung emigrated to Canada in the late ’80s and announced his retirement from singing. He returned to Hong Kong screens, however, in a series of highly celebrated film roles in the ’90s, gaining international acclaim for Farewell.

The art form at the film’s center, Beijing opera, is characterized by its use of colorful face paint, elaborate costuming, and daring acrobatics to stage tales typically based on Chinese history or mythology (this is a seriously impressive and fun example I recommend watching). In Chinese performance tradition, operas are very rarely performed all the way through as written. Rather, troupes cycle through scenes from a repertoire of different works. As a duo, Dieyi and Xiaolou’s signature performance is a scene from the titular historical opera, Farewell My Concubine: The Chu king, played by Xiaolou, is surrounded by his enemies and begs his concubine, played by Dieyi, to abandon him. She refuses and commits suicide with his sword in order to die beside him.

Farewell is a groundbreaking and visually stunning work of queer Asian cinema, intimately intricate in its portrayal of Chinese opera, and also probably the most upsetting movie I’ve ever seen.

The film is saturated in the violence of its historical injustices and it doesn’t let you forget it for one second. In the first five minutes, a young Dieyi’s mother chops off his extra finger with a meat cleaver to make him acceptable to the troupe. The tone is set brutally and irrevocably for the next two hours and 46 minutes.

Its first act is unrelenting in portraying the abuses suffered by Dieyi and Xiaolou as they’re groomed for stardom. For much of its history, Beijing opera training was known for its brutal teaching practices. A life as an opera performer was for children from poor and working-class families, and there was a notion of “beating the opera into” trainees. In its early years, it followed older opera traditions in frequently sexually exploiting its dan actors, who in their feminine roles were expected to prostitute themselves to their patrons.

But for a select few who could weather the harsh training, stardom awaited. Well into the tail end of the 20th century, Beijing opera schools were producing some of the greatest action stars and martial artists to come out of mainland China and Hong Kong, with pupils like Sammo Hung, Yuen Biao, and Jackie Chan.

In his memoir, Jackie Chan describes being sold to China Drama Academy on a decade-long contract at the age of seven. Training began at 5 a.m. and lasted until midnight, beatings were frequent and severe, and a strict hierarchical system encouraged older boys to terrorize younger ones. Chan writes that the practices he trained under are illegal today, and he doesn’t “regret the end of that era.” However, he reflects with complicated nostalgia, “As harsh as it may have seemed, it was a system that had worked for decades, even centuries…and to tell the truth, younger generations of performers aren't as good as we were.”

Chan espouses a common sentiment among appreciators of Beijing opera: acknowledgement of the antiquated and violent training practices, yet mourning of the period that originated them. Critic Helen Hok-Sze Leung writes, “The ambivalent feelings invoked—disgust at the abusive violence on the one hand and admiration for its end results on the other—illustrate a common cultural response to a historical irony.” It’s cultural reckoning wrapped up in nostalgia; for better or for worse, nothing portrayed in Farewell, from the shifting political reigns to the beauty and cruelties of Beijing opera at its peak, can last forever.

Another wonder of Farewell is that it’s an astonishingly queer film for its time, and (somewhat unfortunately as it’s been three decades since its release) still easily the most famous and impactful queer film to come out of mainland China.

Cheng Dieyi lays eyes on Duan Xiaolou when they are children and never stops looking at him. As their adult lives and ideals tear them apart—Xiaolou marries a courtesan and refuses to take opera as seriously as Dieyi—Dieyi stays hopelessly jealous and becomes more and more obsessed with his operatic role. On the stage, at least, they can act at being in love.

At one of the most brazenly gay and iconic moments in the film, Dieyi grabs Xiaolou and shakes him hard as desperate romantic music plays in the background. Leslie Cheung is radiantly devastating as Dieyi, exclaiming that he wants to spend the rest of his life together with Xiaolou on stage—“I’m talking about a lifetime! One year, one month, one day, even one second less makes it less than a lifetime!”

Xiaolou continues refusing to understand him, and the years pass anyway. Dieyi settles into a relationship of convenience with his patron, the weaselly opera connoisseur Mister Yuan, and takes to dressing him up in Xiaolou’s stage costume as a crude imitation of the real thing.

The 20th century roars by. Towards the film’s end, the CCP has come to power and the Cultural Revolution is fully underway. Opera is set aflame as one of the Four Olds; Dieyi and Xiaolou, disgraced pre-revolutionary performers, are dragged out into the streets in a struggle session. (It’s hard to overemphasize the magnitude of betrayal and paranoia in filmic portrayals of the Cultural Revolution; director Chen Kaige drew on his own experience and shame denouncing his father.) In the film’s climax, Xiaolou and Dieyi are pressured into mutually betraying and denouncing one another in front of a crowd, signifying the fiery demolition of the old world.

The film’s final act takes place eleven years later, at the two’s first meeting since the struggle session’s aftermath, and their final performance together. They rehearse their signature scene and—like many times before—Dieyi, the concubine, takes the sword of Xiaolou, the king, and brings it to his throat. I don’t have moral qualms really about spoiling the ending of Farewell My Concubine because it’s not so much a spoiler as an inevitability (like how I don’t think you can meaningfully spoil Titanic or Hadestown). It’s clear even before the movie starts—and reiterated by Dieyi several times throughout—that the concubine must die, by the king’s sword, by her own hand. This last time, Dieyi makes the story real.

It’s spring now and it’s ending soon. This month marks twenty-two years since Cantonese superstar and Hong Kong golden boy Leslie Cheung jumped from the 24th floor of the Mandarin Oriental hotel in Hong Kong after a long struggle with depression. If you ask any Chinese person from my parents’ generation, they turn deeply regretful when talking about him. They also, without fail, will mention that they thought it was a joke at first since the news broke on April Fools’ Day.

Leslie Cheung’s death was one in a line of catastrophes that hit Hong Kong in 2003. A combination of the SARS epidemic, uproar over proposed anti-sedition law, and political and economic unease that had been building since the 1997 handover had bubbled to a boiling point of weariness and frustration. For many, Cheung’s meteoric rise to stardom in the ’80s and ’90s paralleled Hong Kong’s cultural and economic prosperity, and his death was a symptom of the city’s decline.

Afterwards, sociologist Ng Chun-Hung reflected, “Our era has officially ended and a new uncertain one has begun. Hong Kongers are set to stumble and crawl.”

Besides sounding the death toll of an era, Leslie Cheung’s suicide drastically recolored viewings of Farewell and drew inevitable comparisons to Dieyi’s on-screen suicide. It seemed that life had imitated art: Like the film’s protagonist, he was too much for the present time. Even in life, he had already become anachronistic. His real-life sexuality—which for years had ranged from wide speculation to open secret to coyly confirmed fact—could now also be superimposed over the tragic image of Dieyi. It’s somewhat troublesome but also inescapable, and not at all unique to Hong Kong iconicity, that when an artist dies tragically young, their art is reinterrogated and reframed in the context of their death. I wonder now how much of the meaning behind Farewell has become inseparable from Leslie Cheung’s ghost.

In director Chen Kaige’s memorial of his star, he says that he once had a dream where he spoke to him and was unable to differentiate him from Cheng Dieyi. He exclaims, “Indeed, Leslie Cheung is Cheng Dieyi.”

With Cheung’s death, his legacy as a “queer icon” was quickly solidified by queer organizations and mainstream media alike. While I don’t disagree with this classification, I have generally complicated feelings about the romanticization of his death and the oversimplification of his queer persona.

In life, Cheung cultivated a thoroughly queer performance aesthetic but simultaneously shied away from explicitly labelling himself for much of his career. In Undercurrents: Queer Culture and Postcolonial Hong Kong, Helen Hok-Sze Leung analyzes his ambivalence around publicly acknowledging his queerness: In addition to his established visually queer stage persona as a singer, in the 1990s, he took on a succession of high-profile gay roles in films from Farewell (1993) to He’s a Woman, She’s a Man (1994) and Wong Kar-Wai’s Happy Together (1997). When interviewed, he discussed their queer themes seriously and compassionately, but from a distance. In his 1997 concert tour, he dedicated a love song to his lover of 20 years, Daffy Tong, but referred to him only as his “mother’s godson.” He addressed his own sexuality only once, in a newspaper interview where he pushes back against a claim that he’s gay by making the correction that, rather, he’s bisexual.

In an old interview, Cheung says with a laugh, “I don’t wish to be Cheng Dieyi. As a person, I’m much luckier than him…but I do love playing tragic characters.”

For years since, Leslie Cheung’s death has been wrapped up with Hong Kong’s transition to Chinese authority and its gradual decline, as well as the strangulation of queer film and art due to mainland influences. It’s conflated with its particular time, and Cheung is transfigured into an icon of Hong Kong’s golden era, and a queer one at that. His plight, in life and on screen, becomes Hong Kong’s. In “Changes Manifest,” Emma Tipson analyzes a selection of Hong Kong films from just pre- and post-handover, writing that they echo “fears that the Hong Kong identity is one that is destined to be forgotten…a cultural autonomy which is feared to be consigned to the past unless preserved through filmic devices.”

I think that I do understand the compulsion to conflate. When I’m watching his movies, old concert footage, listening to his music, digging through old news articles, I feel a deep enamoration with a time and place, or rather, his time and place. I’m not from Hong Kong and I was never alive at the same time as Leslie Cheung, but I miss him a lot. Is that alright to say?

Like how Beijing opera, in all its complexities, will never exist as it did a century or two prior, I don’t think there will be a Chinese movie like Farewell My Concubine again, at least in the foreseeable future. It’s epic, it’s violent, it’s fragile—it’s history. It’s about Hong Kong even when it’s about Beijing. It’s about art. It’s about trying and failing to hold on to a time and a place that’s already gone.

How do you hold on anyway? What’s real, what’s fiction? The film ends back at its opening shot: Cheng Dieyi rehearses with Duan Xiaolou for the last time, eyes trained on his sword, saying with everything but his voice, The sword is real. I can raise it to my own throat and have it be real—and by doing so I can make us real.

When is it time for the opera to end? Look, it already has.