The age-old adage, “Fool me once, shame on you. Fool me twice, shame on me,” appears to have been forgotten by our generation.

Frequently, in conversations with my peers, we obsess over why somebody behaves toxically toward us. It should not come as a surprise that a generation of self-proclaimed “empaths” seeks the altruistic good in everyone. Among modern teens and young adults, justifications for another’s cruel behavior dominate conversations and “debriefs,” and are received with a chorus of sympathetic hums and nods. From mental illness to childhood trauma to mere everyday stress, we accept rationales for toxicity instead of demanding accountability.

Charli xcx and Sky Ferreira’s collaboration on the track “Cross You Out” has been peppered throughout my playlists since my teenage years. The anthem addresses conflicting feelings of grief and euphoria that follow eliminating a toxic person from your life. Over the past several years, my application of this song to my own life has shifted, from familial estrangements to romantic entanglements to broken friendships.

Built a world / All in my mind / All on my own / Will I survive?

The act of cutting someone off always feels unduly extreme, a definitive end that the song encapsulates with its distorted and booming baseline. The threshold of passion and turmoil you need to reach before deciding to cut someone off necessitates having known the person deeply. I’ve both heard myself and listened to others list all the positive qualities of a person who hurt them—after detailing the extent of that hurt—as though the past experiences of their favorable traits will cancel out their present actions simply by being spoken into existence.

“But we used to write each other letters over winter break.”

“She used to confide in me about everything.”

“He was always so generous.”

The past tense can be an alluring temptress, where the context of the present has no place, and everything is as it once was. After all, if somebody exhibited certain positive behaviors at one point in time, why can’t they do so again?

Melt me down / One piece at a time

I do not think the issue is that we tend to think of people as good or evil, black or white, all or nothing. I believe most people would agree, or say when asked, that people are gray. However, this often seems to me to be yet another excuse—a blanket assessment of all people as equally prone to good or bad behavior—that ignores the fact that some people are, in fact, dark gray or light gray. Some people consistently prioritize their own feelings above those of their loved ones. Perhaps they leave stinging comments intended to wound when in a bad mood. Perhaps they talk behind your back or exclude you from social circles or give you the silent treatment. And then, when the rain clouds have dissipated from above their head, they greet you with a warm glow, embrace you, and confide in you once again. Emotionally mature individuals, on the other hand, might instead interpret a bad mood to mean it's time to go on a walk, take a break, distance themselves from others until their breathing evens out. When they come back, they apologize if they slipped up, take accountability, and move on, having learned a lesson.

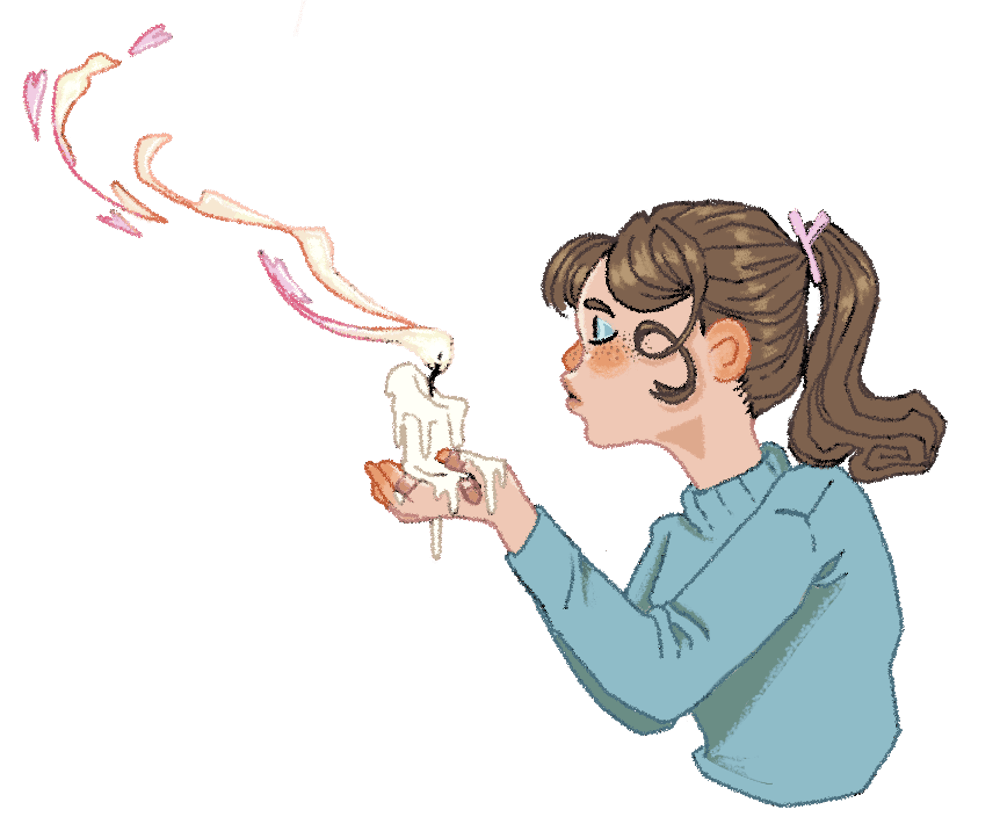

Giving grace for these instances might be, as “Cross You Out” purports, like holding a candle as it melts down to the wick. You can allot wax to each person to burn—to some, you might be able to give more; to others, you might have less tolerance. A burn on the hand can be prevented by the wax for only so long until the flame reaches you. Then, the only thing you can do is get away from the fire.

When you’re not around / I’ll finally cross you out

Key to the emotional maturity of “Cross You Out” is the condition in the repeating lyrics of its chorus. “Crossing someone out” can only occur when they are not around, or, rather, you do not cross someone out and then kick them out of your life. To me, the message of the song is that peace can only come with distance.

Distance can be easier said than done for either party. Sometimes, we are surprised by how easily another person accepts our distance, and we feel compelled to return, to remind them that we are significant in their life. Other times, distancing yourself from another person, especially a selfish person, can feel like ripping off a bloodsucking leech or a decapitated cockroach, somehow holding onto life and scuttling back.

There is a permeating sentiment in our online generation that we must be constantly connected—a sentiment made all the worse by the confines of a college campus. You text your closest friends during class, who are also your roommates. You follow everyone on Instagram and see the inner workings of their lives through their daily stories. Every Partiful invite lists just slightly different conglomerations of the same 80 names and faces. It has never been easier for a toxic force to cling to you in this day and age, and even more so at this time in our lives. They spam your texts, they’re in your living room, they subtweet you online, they RSVPed to X, Y, and Z weekend events. Today, a new and sizable bulk of the onus to “cross someone out” is on the crosser-outer to go beyond just distance in its literal sense—it is to mute Instagram stories, to have the strength to ignore the chemical pull of notifications, to rise against the dread of inevitable confrontation. It is exhausting. It is, nevertheless, essential.

I’ve become someone better / Now I look in the mirror / And I learn myself better

Throughout our years at Brown, my close friends and I have frequently circled back to philosophizing on the meaning of forgiveness. I have always felt that the phrase “forgive and forget” is an oxymoron; rather, the saying should be “forgive or forget.” To some of my friends, forgiveness is a personal matter of letting go, reflecting on a wrong that someone committed against you, and not letting it bother you anymore.

I have reached that internal point of letting go with several people in my life, though I am not so sure that I would call it forgiveness. This article may make it seem otherwise, but I do believe in forgiveness. In fact, the act of “crossing someone out,” for me, is the only way to set the stage for forgiveness. An old loved one’s candle whittles down and burns your hand—instinctually, you have to get away. That is not to say that a new candle cannot be cast and molded. Yet, in the spirit of fairness—of the relative equality of effort that must mark any relationship—the other must ultimately take the initiative to re-shape the wax and cultivate the flame. But, unless that happens, keep your distance and hold fast to your principles. Don’t keep your hand burning under a hot flame. You’ll become someone better.