My move to Providence in August of this year began with a humbling initiation: the worst haircut I’ve ever received. My fine hair has always been one of my biggest insecurities, second only to the persistent hormonal acne that’s more indecisive and temperamental than an angsty teenager. Thanks to years of consistent deep conditioning treatments and the abolition of hot tools from my routine, my hair finally grew past my shoulders and has, at times, even held a moderate shine.

Just days before Brown’s orientation, and on the day after my birthday, I decided to treat myself to a polished new cut, eager to feel fresh and pretty for my first steps onto campus. But, after a hurried snip, the stylist at a hip downtown Providence salon spun me around, yanked off the cutting cape, and ushered me out like a pageant contestant who’d been announced as first runner-up after an unimpressive response to an on-stage question. I barely had time to catch a glimpse of myself in a distant mirror. Oh…oh no! I paid, forced a smile, and rushed to my car, clutching the ends of my newly guillotined locks.

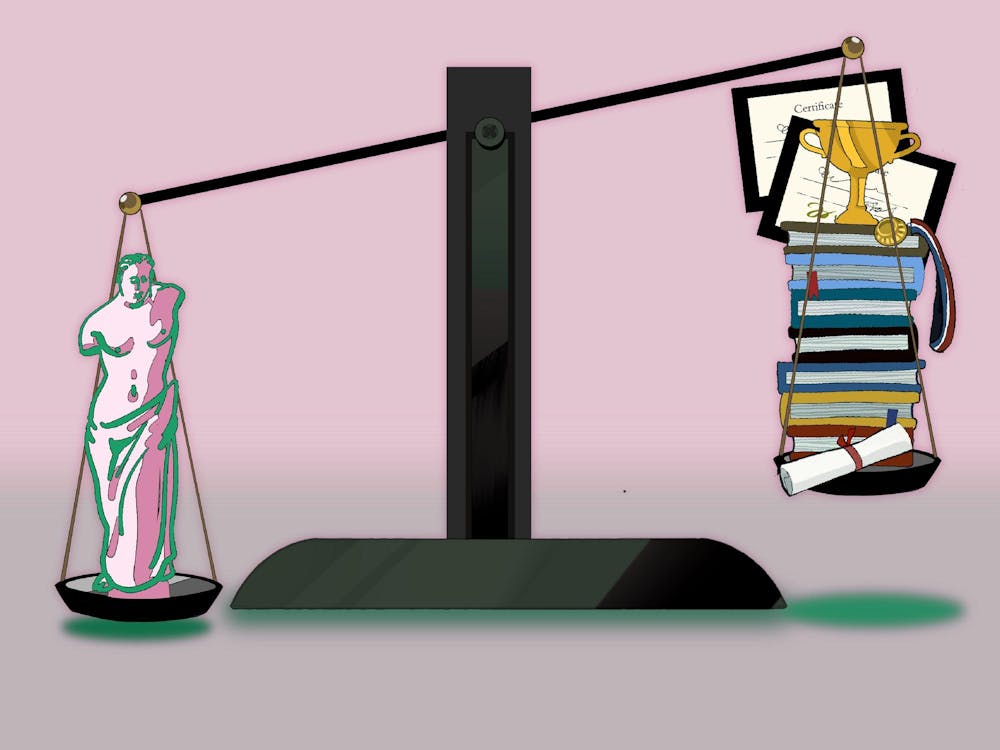

I avoided the car mirror the whole drive home, unwilling to face whatever disaster awaited me. When I finally looked, my heart crumbled. Six inches shorter, uneven, and as dry as stale bread. My worst fear was realized. I looked…ugly. With tear-filled eyes, I tried to twist, curl, and straighten my way back to pretty, and repeatedly failed. I felt hideous. I spent the next few weeks in either a high ponytail or a slick bun to conceal my embarrassment. My identity, so often wrapped up in my appearance to others, hung in the balance of my asymmetrical tresses. As my confidence shrank with every uneven strand, I began to wonder why my sense of self-worth was so entangled with something as superficial as hair.

Why did feeling “pretty” hold such power over how I moved through the world?

That question lingered weeks later as I scrolled through coverage of two glossy cultural comebacks: the return of the Victoria’s Secret Fashion Show and the latest Miss USA competition—a stage I once sought to conquer.

Victoria’s Secret, disgraced by cultural jurors, disappeared from the limelight to reinvent itself and appease a highly critical audience. Similarly, Miss USA has been mired in scandal after scandal, desperately clinging to relevancy. The revived VS Fashion Show promised to represent all women, showcasing a diverse ensemble on its glittery pink runway. After the show, discourse spitfired as think pieces sprouted in every corner of the digital landscape. Enthusiasts ooh-ed and ahh-ed as cynics picked and prodded. Pop culture analysts at home on their keyboards volleyed assessments weighing the pros and cons of supporting the revitalization of a brand that historically upheld the idea that there was one universal standard of beauty. A nonbeliever called out their distaste for the fashion show in a comment under a video featuring the ultimate archangel, Candice Swanepoel: “We can’t forget that this is just capitalism that positions beauty as the ultimate goal.” This comment received hundreds of likes. A sharp retort fired back: “What’s so wrong with being pretty?”

Initially, I agreed with the cynics. The VS Fashion Show does profit off of women’s bodies in crude ways, embedding a certain idea of beauty and desirability into the minds of girls and women of all ages. What we see on TV shapes our worlds and our minds; like any corporation, VS should be held responsible and acknowledge the ways in which they have distorted women’s self-images with the pressure to conform to a size zero. Both the VS Fashion Show and Miss USA have sought to rebrand and reimagine their identities and what it means to be beautiful in 2025. It feels natural, then, to pose the question: Have they succeeded? But I itch to ask another. Can industries anchored in unrealistic standards of beauty ever be…better?

On these stages, is there room for tangible improvement, or should glamorous parades of women once displayed on TV be consigned to the archives of old YouTube videos and VHS recordings of early fashion shows and pageant runways? Miss USA’s social media posts pair heavily edited photos with lyrical captions such as “Empowering the new era of beauty queen” or “More than just a pretty face.” Modern pageants claim to be creating a new future for aspirational and driven women. But the prerequisite remains: You must be beautiful. As a former Miss USA contestant, I can assure you that the notion of empowerment is a ruse.

The organization touts a mission to uplift the next generation of women. In truth, their efforts revolve around physical beauty, thinness, and glamour. They lean on the notion that the swimsuit contest is about health and wellness, only to feed contestants pizza and chicken tenders throughout the competition. Contestants dedicate hours to their physical presentation, adhering to one standard of beauty, only to perform on stage for less than three minutes total, speaking for even less. The winning formula is simple: Smile at the judges; apply vaseline on your teeth if needed to maintain said smile. Hit a sharp T-pose at the end of the runway; if you feel like you’re about to fall, squeeze your butt! And above all else, be pretty. Like, really pretty. If you’re not, you don’t stand a chance—but they want you to believe that you do. They’ll tell you that you as you are is enough. It’s not.

When beauty becomes a prerequisite, every woman’s worth is placed on a fragile foundation. Any deviation from the ideal—a bad haircut, not being a size zero—can feel like failure. I have lived that stomach drop in front of the mirror, at Miss USA and here in Providence, mistaking aesthetic disappointment for personal defeat. But the pressure to be pretty is not just individual, it is systemic. It governs who gets attention, opportunity, even credibility. Pretty becomes the password to social status and ultimately, belonging. When we keep rewarding beauty above all else, we teach girls and women that being seen matters more than being heard.

The newly crowned Miss USA, Audrey Eckert, is a young woman from Nebraska. She is a former NCAA Division 1 athlete and a marketing coordinator for a Certified B Corp fashion company. The top comment below her crowning photo reads: “Miss USA is boring now, they only crown ugly women.” Ugly has become the ultimate insult. It's more harmful than uneducated, unkind, or unsuccessful. But maybe it is only when we stop fearing it that we can begin to be free of the shackles of pretty. Audrey is not ugly. But even if she were, what’s so wrong with ugly?