The great American novel, the ultimate titan of the Western symphonic tradition, and a chronic mental illness—bear with me.

As my summer vacation was coming to an end, I finally motivated myself to finish reading Moby-Dick. I had set out to read the goliath of a novel a couple of years prior, but I put the book down with less than 50 pages left for reasons I can’t even begin to remember. Now with both the time and the energy to return to it, I finally read for myself how Ahab, the monomaniacal captain of the whaling ship Pequod, sailed to confront the white whale. Ahab is obsessed with finding and killing Moby-Dick. And despite the knowledge that pursuing Moby-Dick will likely be a mortal mistake, Ahab does it anyway only to find that, in the end, death and destruction await as promised. To most, Ahab epitomizes insanity; to me, Ahab makes perfect sense.

I have obsessive compulsive disorder. I was surprise-diagnosed with OCD right before the pandemic began in my sophomore spring. I say it was a surprise because I went to Health Services for persistent stomach problems and I left with an OCD diagnosis. Maybe I should’ve known when the doctor abruptly shifted from talking about my stomach to asking questions like “Do you find yourself completing certain rituals in order to get rid of a negative thought or prevent some disaster from occurring?” I was hoping to find definitive answers to my questions and I walked out with what appeared to me as an ambiguously treatable mental illness.

Without wading too deeply into the particulars, it is important to know that OCD is composed of two main components: obsessions and compulsions. Obsessions are persistent negative thoughts that produce lasting feelings of fear, anxiety, and shame, whereas compulsions are the repetitive actions or rituals that one completes in order to assuage these emotions. My most debilitating obsession revolves around my inordinate fear of “contamination” from things like dirt, germs, excrement and the corresponding compulsion to wash my hands.

At the time of my diagnosis, I would wash my hands vigorously for 2-3 minutes under burning hot water, dry them, immediately repeat that process, leave the sink or bathroom, walk back to my room, and then immediately return to repeat the hand washing procedure at least two more times before feeling like my hands were clean. An integral part of the life of an obsessive-compulsive is knowing that engaging in these compulsive behaviors makes no logical sense. And yet we continue to give in to the anxiety; we continue to feed the beast. In doing so, we fall further and further from the path of a normal, healthy life as our days become saturated with exhausting, mindless rituals.

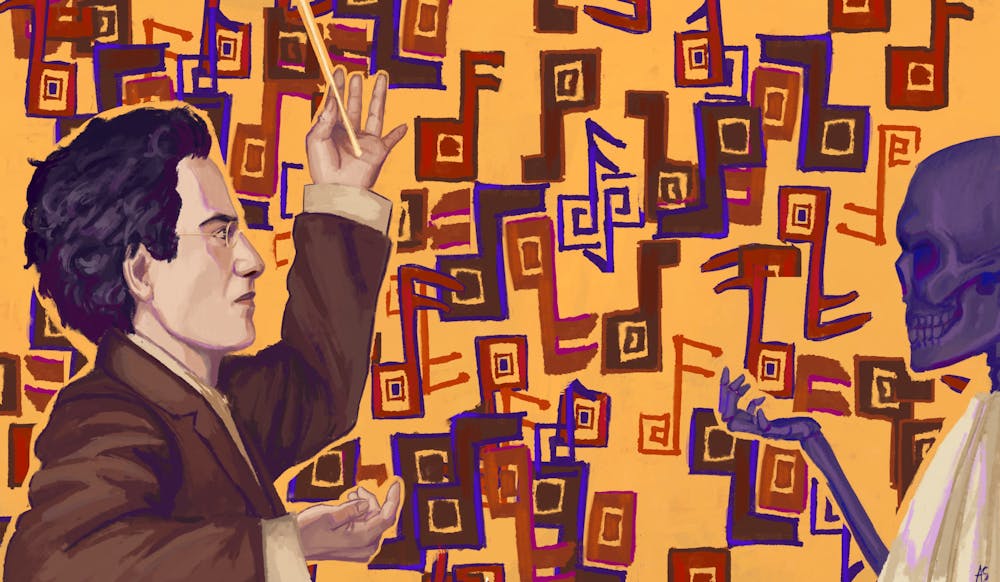

It was in the period after my OCD diagnosis, when I first began to consciously overcome my obsessions and compulsions, that I discovered the music of Gustav Mahler.

Now, I’m not a musician, nor do I have much of an aptitude for music theory. Though I cannot and will not satisfy the seasoned musicologist, my understanding of Gustav Mahler’s music might resonate with those for whom music holds the key to another dimension of feeling; those who love music because of its mysteries, not in spite of them.

Mahler’s most famous piece of music is his Adagietto. A lyrical interlude scored for strings and harp within an otherwise intense symphony, the Adagietto is a wordless expression of Mahler’s undying love to his eventual wife, Alma. In Mahler’s Adagietto I hear a sonic reflection of my obsessive-compulsive mind. Just as performing my ritualistic compulsions only prolongs and deepens my anxiety, this symphonic movement feigns resolution only to return and repeat the same melody over and over. Listening to the Adagietto is like feeling your lover’s chest rise and fall with the rhythms of their breath; it’s a drug.

It is impossible to say if Mahler had OCD, but it is evident from the historical record that he possessed an obsessive personality. As an opera conductor across Europe, Mahler was known for his domineering style of leadership; he demanded absolute perfection. Mahler’s perfectionism ran so deep that as the director of the Vienna Court Opera, he made efforts to dictate the hygienic standards of the ushers.

But the concept at the forefront of Mahler’s mind was death. Not exclusively death as the somber and terrifying end we all must face, but death as a transition from this living reality to some higher existence, a noble farewell to the material world, a transcendence. Mahler’s final compositions embody this obsession. The last song in his symphonic song-cycle titled Das Lied Von Der Erde, (The Song of the Earth), is called “Der Abschied” or literally “The Farewell.” Mahler inscribed the manuscript for his Symphony no. 9, the final symphony he completed before his death, with cries of “Leb’ wohl! –“farewell!” Life and love are inseparable from departure. It is not that Mahler had some subconscious death wish, but rather that the finality, universality, and mystery of death offered Mahler a creative promise, a way beyond the suffering of the earth. Coming to grips with the end, with the need to let go, is all that there is; for even if we choose to deny the various ends that lie waiting for us all, like Ahab, they will consume us all the same.

Someone close to me once said that “you know that you love someone if you’d grieve their loss.” Love of life and of other people manifests in the volatile space where our hope of eternity and our understanding of mortality rub shoulders. We believe in love’s power to extend beyond ourselves and our momentary station on this earth but we love all the more because we know that we must one day lose everything. The music of Gustav Mahler documents his weltschmerz (world pain), that heaviness felt by those for whom life is an obsessive search for truth. Holding tight, then letting go—obsession, then farewell. The awareness of loss, the continuous struggle to stave it off, is not the antithesis of love but its necessary counterpart. Mahler helped me understand that it’s okay to obsess—OCD is a part of who I am and how I take in the world. But it need not be all of me. It is also okay to acknowledge aspects of life as they end and fade away without shame and without judgment. Each of us holds this capacity to say farewell and live better for it.

Herman Melville constructed Moby-Dick out of 135 chapters; only the last three short chapters concern the confrontation between Ahab and the whale. That’s less than 30 pages out of more than 500. Just before his clash with the hated whale, Ahab’s resolve to see his mission to the end momentarily wanes as he remembers the life he left on Nantucket. But resigning himself to fate, Ahab presses on. The name of this chapter before the final three-part chase: “The Symphony.”

Once more we return to Mahler’s Adagietto. Any conductor organizing a performance of a piece holds a certain degree of interpretive freedom, especially in regard to the tempi. Depending on the speed at which a conductor takes a movement, the same music can produce different emotional responses. The slower tempi of Leonard Bernstein’s recording of Mahler’s Symphony no. 5 with the Vienna Philharmonic turns a wordless love song into a funeral elegy–Bernstein famously conducted the Adagietto at Robert F. Kennedy’s Funeral Mass. Much ink has been spilled debating the merits of this or that approach to the movement; should it be a light and breezy ode to unabashed, obsessive love, or should it be a slow ode to sorrow, a paean to death? I believe it can, and should, be both: obsession and farewell in tandem.