“It’s all about a larger journey: Your work is never done,” Erin Niimi Longhurst writes in her book, A Little Book of Japanese Contentments. That's the beauty in it. The journey is the process and importance of discovering what keeps you going. It’s about learning to “let go of the things you can’t control.” Learning to “find balance, take breaks, savor the silence.” Learning to find clarity, regroup, and persevere through challenges. Learning to find and record the things that had made you feel happy during a time that seemed hard. Here are some methods Niimi Longhurst suggests:

Finding your ikigai

Embracing wabi-sabi and kintsugi

Understanding yourself through the body

Shinrin-yoku: nourishing through nature

Ocha and chado: wa, kei, sei, jaku

Calligraphy: ideas of practice, resilience, striving to achieve perfection

The Japanese home: transformative spaces

Discovering your ikigai, or purpose, is essential to the longevity associated with Japanese lives. It is one of the central ideals that contributes to living a happy and content life. It’s about discovering the fire within us—that for some may be burning bright, but for others, could take a quieter form. Finding your ikigai is a long process that is slowly revealed to you through moments of understanding yourself. Ikigai is the fuel for your motor, but not the destination. There is a proverb in Japan and China that can be used to understand the process of finding your ikigai: “If you try, you may succeed. If you don’t try, you will not succeed.” Finding your ikigai helps you establish clarity, allowing you to focus on the more important aspects of your life. It tells you it’s time to let go.

Wabi-sabi is something that I have encountered a lot, having based my IB art exhibition around it. It generally summarizes the beauty of imperfection and impermanence. It means accepting the natural aging process, “being able to recognize, remember, and find happiness in the moments that have passed.” It’s about the transience of life, and valuing what we already have. In understanding wabi-sabi, you learn to be grateful for everything you have, reflecting every day. As a result, you almost develop a skill of not being afraid of death. Even if death comes, you will appreciate everything you have received. Niimi Longhurst also discusses the concept of Mono No Aware—“The Bittersweet Nature of Being”—pointing out an example that resonated deeply with me: at one point in your childhood, your parents decided to pick you up or lift you onto their shoulders for the last time. It’s the reflection and observance of the world around you. It’s the appreciation and understanding of the nostalgic happiness (natsukashii) that comes with moments you have experienced. You find comfort in the ideas of imperfection and impermanence and learn to be more forgiving with yourself.

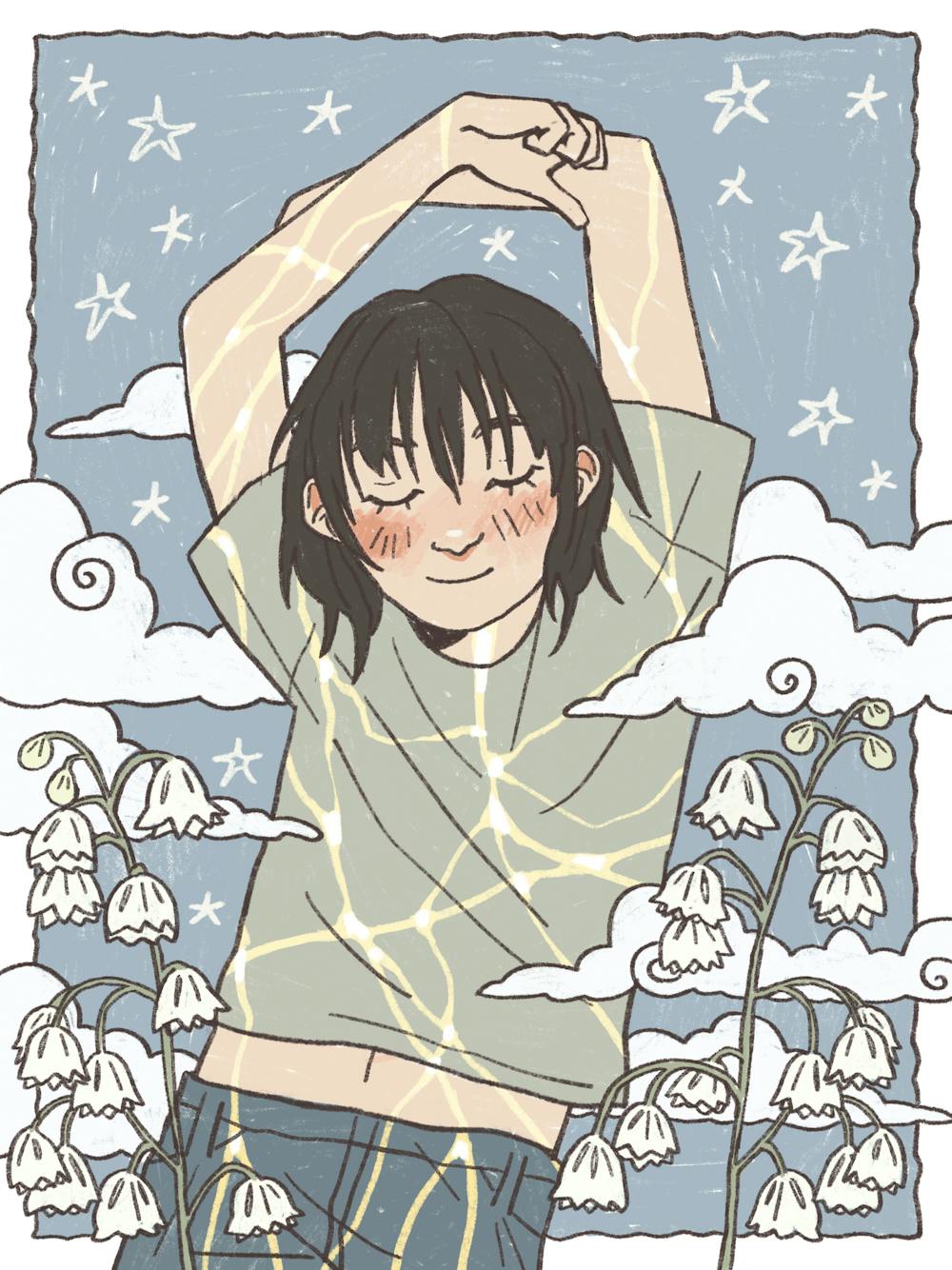

Kintsugi, the art of repairing broken pottery with golden lacquer, highlights this point of embracing the beauty of imperfection. In this case, disfigurement or defect makes it even more beautiful. Niimi Longhurst writes, “Nothing is ever truly broken, no matter how painful it might seem at the time.” By applying this philosophy to life, you will hopefully realize that you are strong in your own way. You can never be beaten down. If a crack or tear appears in your life, acknowledge the disappointment, sorrow, loss, and feel what you are feeling—then repair it using golden lacquer. Highlight it and come out even more beautiful.

Apart from understanding through the kokoro (heart and mind), it can be easier to experience these philosophies through the karada (the body). The first of such experiences is shinrin-yoku (forest bathing), the process of being healed by nature. By taking a long walk through the winding forest, you can practice mindfulness and use this time as an escape to seek clarity, not avoidance. Lacking a fixed destination does not equate to a lack of purpose. It is about “getting you somewhere in your mind, rather than your body.” The author also lists out absolutely beautiful words that encompass the natural phenomena that might be seen on the journey. These include komorebi, the kind of light you see in a forest where the rays of sun are filtered through the leaves of the trees, and kawaakari, the way moonlight reflects off a river and brightens it. In both ways, it elucidates the vitality of light against a still, calm backdrop of the forest or the waters, representing an ephemeral sense of beauty associated with the passing of time. Forest bathing can help clear your mind, rediscover your ground, and find greater content in the small things as you reconnect with the natural forces of life.

Ocha (green tea) and the tea ceremony is also something that I heavily explored in my art exhibition. The chado (tea ceremony) serves as a way of centering oneself, exercising the principles of tea founded by tea master Sen no Rikyū. The four principles: Wa (harmony), Kei (respect), Sei (purity), and Jaku (tranquility), are things that we should strive to achieve in our everyday lives. As the author puts it, “As human beings, we want to live peacefully with others and to be respected.” The process of the tea ceremony, which involves high degrees of all the principles, builds a sense of community and solidarity, and of finding the balance in between. The mundane daily action of having a hot cup of tea cleanses the mind, body, and soul, as you become focused on your ikigai.

Calligraphy in Japanese and Chinese culture represents the beauty of maneuvering ink, elucidating a tension between the paper and the brush. In this sense, you learn the unforgivingness of the paper, the beauty in permanently capturing this fleeting moment. Calligraphy highlights the ideas of practice, resilience, diligence, and discipline in striving to achieve perfection through repetition. It develops a strong sense of connection with oneself, especially in the digital age.

Finally, the Japanese home is most memorable as a transformative space. Maximizing space with multifunctional rooms, you understand the fluidity and flexibility that allows this space to become home. The design is focused on withering, rustling, and aging. Once again, it’s intended to reflect that idea of the passage of time.

Thus, putting these ideas of both the mind and body into practice is about striving for a constant pursuit of self-improvement, accepting and facing the obstacles that arise, and truly learning to let go of the things you can’t control. Remember that you are always in competition…with yourself.

“Find balance, take breaks, savor the silence. Get started.

Embrace the scrapes, scars, and bruises you’ll get from trying.

Fall down seven times, stand up eight. And keep going.”

– Erin Niimi Longhurst, A Little Book of Japanese Contentments