It is easier, sometimes, to be outside of oneself.

—

She sighs into the seat two rows behind the driver. Her profile shifts across the window. It leans back, forward, back again, it tilts up, then to the side; in the window are eyes couched in pouches and a pair of pressed lips; the eyes see their doubles on the dark pane; in the window, the eyes slip away, and her profile takes their place.

If she hadn’t observed the woman sidle into the row in front of her, she wouldn’t have known anyone was there. A hand crawls around on the ceiling and finds a vent. She watches the fingers scrabble against rigid plastic, searching; the hand retracts from its fool’s errand. She watches the gray seatback like it’s a powered-off television screen.

Voices clump and weave and dissipate, not distant, not close. And the oth-giving it to her tomor-close the blinds plea-no it’s open you can si-hospital for two more we-what she’s gonna do-not saying the gun was in the-funniest thi-not really no. The voices layer over crinkling canvas, creaking plastic, air squeezing, hissing up, relaxing, whooshing out. Everywhere hangs an odor of onions. The tear cups her chin and drops onto her thigh. It was too crowded so-shot her in the-miss you all the-probably shouldn’t deci-getting tested on Tuesday.

—

On Saturday, she was in a skirt and boots that pinched her toes. She had lipstick on. It was a white day. White shirts, white stripes of light on the pavement, white teeth, white underwings, white lettering on shop windows, white sky, white frosting, white hubcaps, white everywhere. All over the sidewalk dashed quick feet. Strollers veered around telephone poles and chairs; pedestrians veered around strollers. The walk sign was on when she arrived at the curb—three times in a row. Down and down and down the street, she stepped heel to toe, heel to toe, clip to clop, one spire meeting cement, then another, with her hair blowing, lifted on a breeze of her own making. She counted one, two, three babies smiling, all innocence.

Her eyes pulled at the corners when she accepted coffee from the man behind the counter, whose age she couldn’t tell; he appeared 30 and 50 years old all at once. It was something in the stubble that stretched up to his ears and gave way to a shiny dome. A circle of light glinted on the crown of his head. After she left the cafe, she recalled the space as it had been, cast in a veil of robin’s-egg blue, dappled with white lightbulbs.

A root distended the concrete; her foot hitched and a droplet of coffee smudged her skirt. She licked her finger and rubbed at the brown spot, then dug at it with her nail. The spot lightened but its edges blurred and the pigment set. The skirt dropped from her fingers; ahead was a dog with flapping ears and tongue, flapping paws. The stain wisped from her thoughts. All that flapping could have been set to a carousel tune.

Her hair danced an inch above her back. She thought she might greet a stranger with a bright smile, maybe discover something delightful and profound in someone’s face.

Once, some summers before, she had seen a girl in the park whose beauty overcame her. She was sure she’d never seen a visage like that, not ever. But once the girl was gone, she couldn’t recall a single feature. For the rest of the day, she searched every passing face for a hint of her ephemeral muse to no avail. If she couldn’t remember what the girl had looked like, how could she hope to find her in anyone else? She had wanted to tell someone about her encounter—that she’d seen the most beautiful girl in the world—but she knew that once she said it aloud, it would no longer be true.

Some months later, she told a friend, and then all she could do was to tell the lie again and again, until she almost believed her own story.

A jolt—her heel snagged another protrusion; the spot returned to her mind. The coffee cup in her hand was empty. Had she drunk it all already? She looked up: the street sign claimed she had walked fifteen blocks. No one on the sidewalk had yet met her eye. Her teeth hid behind impassive, flaccid lips. On all sides, bricks and brownstones came together densely, guarded by pointed ironworks, facades contoured by patches of shadow, warping and lengthening in the wind and lowering light.

Her right foot planted next to her left; she arrived at the doorstep where she remembered, now, she’d been headed. Behind the door were people to whom she was supposed to be important and dear. She stepped over the threshold; her mouth worked the shape of greetings; she felt her cheeks tauten. Bodies thumped into each other and arms swung around shoulders like thick ropes. A reel of inquisitions, of tell me how you’ve been-what are you enjoying about-are you still doing-what are your plans for-how long has it been? rolled over her. She heard laughter chirp from her voice box. Everywhere she looked, she saw hands, some gesticulating over words, others hanging limp; she thought about marionettes. She thought about the stain on her skirt. For hours, she nodded and did not know what she talked about.

By evening, she was tired. She had eaten a salad and drunk a glass of sauvignon blanc. The rest of her stomach she had filled with small rounds of bread slathered with butter, and when the bread ran out, she scooped dollops of butter onto her knife and let the velvet fat melt onto her tongue. It tasted of pleasure, illness, and childhood. She figured that this must really be the taste of growing older. The bill came out to 62 dollars, said the waitress with a placid face.

She had too many more blocks to walk in those shoes, and her head weighed more than usual, and blinking red and emerald blurred the inky streets. Groups of people roved and melded into each other, swarms of them, and at their edges, stragglers, and beyond, loners, vagabonds. She noted the vagabonds and in them found solace and threat.

Of all of the milling bodies, only those belonging to the peripheral solitary onlookers were assuredly real. The vagabonds dangled cigarettes between lips and fingers; smoke broke and diffused against walls. They picked at their nails and pulled their jackets close around their chests. And all around, the groups emitted wordless chatter and blinked with unseeing eyes. She passed through them like vapor. She was the only one going anywhere. Everyone else walked aimlessly. And she was only going somewhere so as not to be here, yet here had no end, no edges.

When she awoke Sunday morning, the tears from the night before had dried beneath her eyelids. She pressed her hand to them and felt that the swollen skin put up buoyant resistance against the pressure of her fingertips. She considered that her enjoyment of the sensation might be a funny thing. Though she supposed she had heard once that the physical act of smiling deceived the brain into releasing dopamine, and perhaps this was not all that different.

She had heard once that there existed a Polynesian language with no conditional tense. No words to express could have, would have, wish I had, if only I had, should have done. She heard that the speakers of this language lived in a state of unparalleled contentment because they did not have any way of conceptualizing regret.

Another time, she had heard that the real David and Goliath were unfairly matched opposite to the biblical story’s convention. David was an expert shot. Meanwhile, Goliath suffered from a disease that caused him to grow to a size so immense that he suffered crushing joint pain. His disease incited the growth of a tumor against his optic nerve, rendering him partially blind. Yet Goliath’s defeat was celebrated as a remarkable triumph of weak over strong.

She once gave three dollars to a homeless man on the sidewalk. When she strode by him the following week, he called out to her, asking for money. She crossed the street and brushed her hair over her face to stop him from recognizing her. She only looked back when, his voice garbled by wind and running engines, she heard him issue his plea to someone new. A bus stopped in front of his post, obscuring from view whether this time he was met with an almsgiver or bypassed once again.

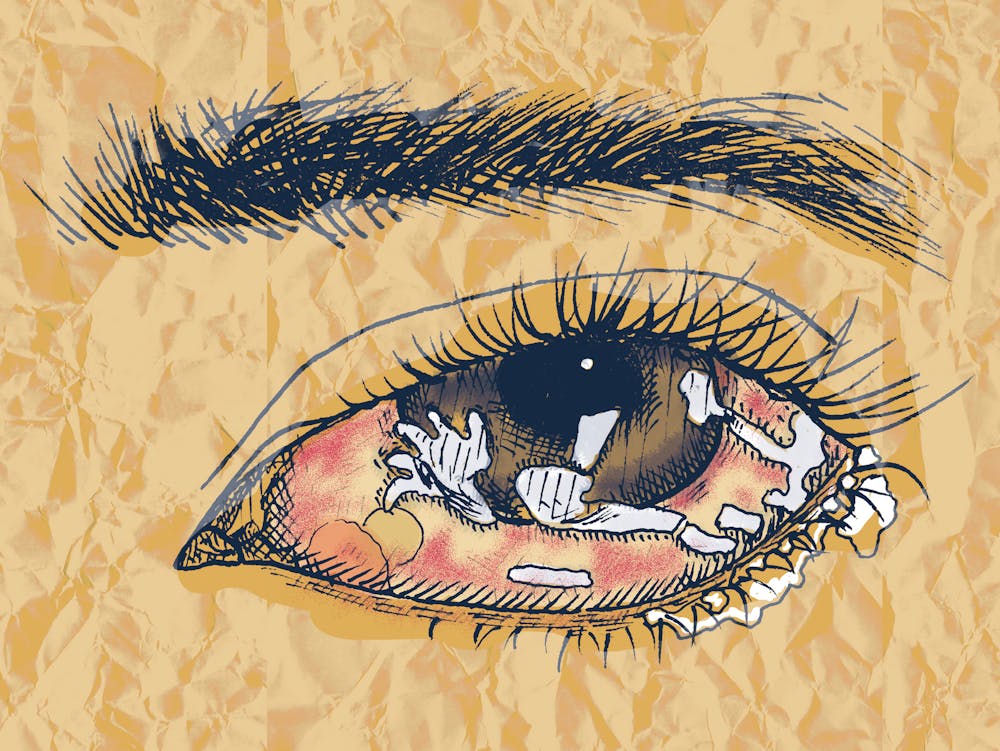

Now the tears were rolling down her cheeks thick and fast. The salt tasted good. Outside, the sunlight broke through the clouds in blue bands. It doused marble walls and windowpanes and sweatered arms in a bright, shimmering chill. Everything was cold to the touch: doorknobs, duvets, keys, toothbrushes, hands, noses, cheeks. This was a shadowless light. A tender pink rimmed her eyes. Her irises shone like glass. Her skin was a clear, light gray, the same tint as the walls, the pavement, the underbellies of the clouds.

Soon, the leaves would begin to fall and curl into husks of themselves. They would crumble underfoot, little pieces of them lifted on breezes that would ebb and return them to the ground, where new feet would press them into dust. The children, as she once did, would toe from husk to husk, in happy pursuit of the brittlest one, that sharpest crackle. She had not been close to a child in a very long time. She watched them from afar these days, watched them until they rounded a bend and were gone.

—

The bus trundles down long stretches. The profile in the window turns again; the face’s eyes do not meet their reflection; they look out past the pane.

The trees slide by. The lakes slide by. The ferns slide by. The housing compounds, the graffitied walls, the exit signs, the billboards, overpasses, wires, fences, poles, tires, pigeons—they all slide by. She sees these things yet cannot touch them. She sits and yet she is moving. She is moving past towns where three restaurants shut down in the same week and a boy is in the newspaper for winning a spelling bee and a sewer line broke and a man found a dog from a missing poster. She is moving across county lines and state lines. The bus rolls onward, onward.

It will take the same route tomorrow.