What does it mean to learn from preservation and reimagination?

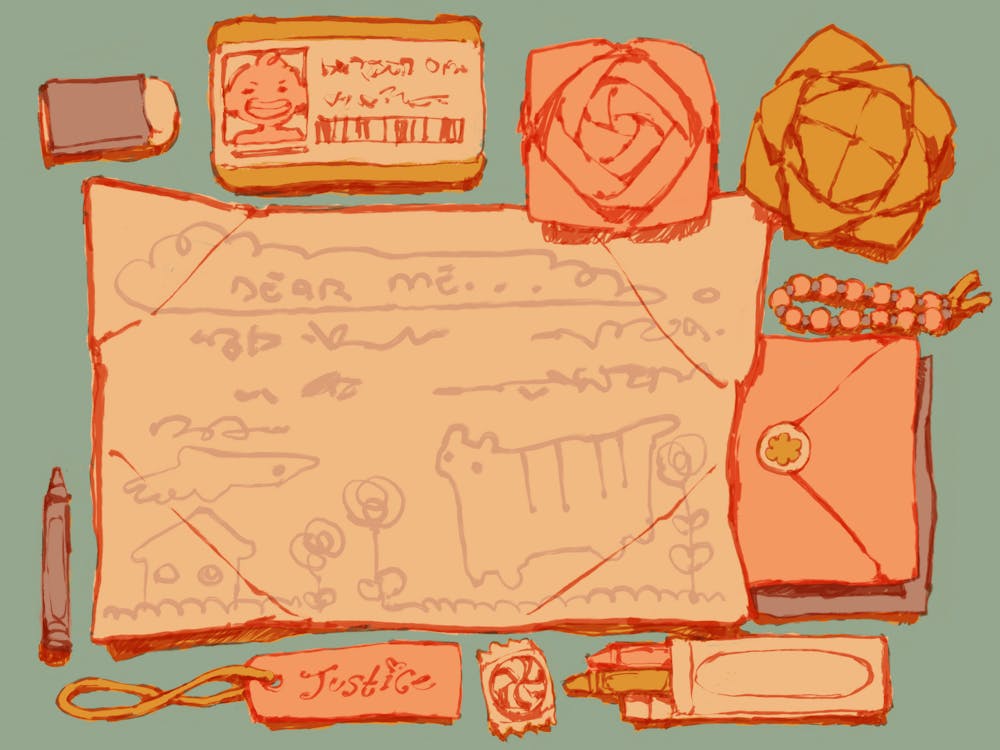

Letters to my future self, sketchbooks of crayon drawings, and origami works lay on the family decor shelf, assembled for the purpose of having connections to my childhood. The letters, written in curvy handwriting, are filled with ideas of what kind of person I thought I would grow up to become. The sketchbooks carried attempts to articulate the world as I saw it then. The origami flowers were folded with patience. Grounding me where I started, these materials create a valuable archive for my life.

In my sociology class this semester, I have been tasked with handling a folder of letters from those incarcerated in Rhode Island prisons. With these personal works, I am to create an archive of theirs, ensuring that I build their narratives off how they have chosen to vocalize their reflections, rather than others’ interpretations. Focused on a collection of letters from those currently incarcerated, I am able to dwell on their handwriting and articulate their personal troubles, struggles, and moments of resilience within the justice system. Alongside this assignment, this class has aimed to mark the importance of preserving such personal materials to allow for the retelling of a story beyond present verbal inquiries. From the mass incarceration issues within our country to the clear discrepancies in court systems, my professor calls us to discuss the flaws within the current system of law. Tasked to read and analyze current work on the jailing and prison system, I am assigned to write journal entries weekly about what I learned in class. This journal, in itself, is a form of archival work where the content and analysis is well-preserved, viewed through my current self’s understanding of the system and its ties to my personal life.

I had often viewed archiving as an act of storage, a means to keep things from disappearing. Looking at the constant display of written books in my hometown museum, I found archiving to be full of the sentiment of striving to preserve, not accounting for what it can do in the present as well. But as I engaged with the art of archival practice in my first sociology class at Brown, I realized that archiving is not merely to preserve, but also to create. This act of authorship is to decide what deserves to be highlighted in remembrance. Giving those who aren’t typically heard a platform to preserve their voices is a form of resistance to the confinement of today’s societal norms.

Many of the incarcerated people we work with in class, who allowed the creation of an archive about their lives, wrote letters about more than what the system has recorded about them. Instead, their files tend to document their humanity, including humor, reflections, and heartbreak. The system likes to place statistics on their stories as a means of accounting for efficiency and performance-based legitimacy. But these letters enable a place for self-expression that extends beyond the walls of confinement, confirming their presence within a world that has rendered them dismissible.

As my professor mentions the role of archivists in the field of sociology, I am invested in the notion that artists and archivists share the ability to reimagine the past, to make it lively and legible in more personal ways. Oftentimes, when learning the history of someone’s life or an event, books depict facts, statistics, and overarching narrative associated with it as a means to produce an efficient and fact-based description. Archives, however, give breath to the stories. Instead of using a detached outsider perspective, archives let me hold the ink and feel the hesitations of the person behind the document. Reading through someone’s writing has a touch of humanity that textbooks and articles often skip over. When an archivist is able to preserve the documents and materials of an individual’s life, we are brought to humility, an awareness that the stories we translate are not ours to control, only to hold.

Archiving can be seen as reconstruction. As an individual holds onto memories, histories, and materials, they have resources to collage an arrangement of something already lived. This reimagined space can be articulated through care. By caring for what has been left behind, we can stop diminishing the original story and promote learning through preservation. The ability to listen and to allow materials to speak their own stories breeds authenticity, providing resistance to the urge to edit someone’s experience into something “neater” than what it truly was. These acts of humility resist societal expectations in favor of authenticity, and amplify the original voice without changing it. To learn from this reimagination is to understand how preserved fragments of an individual's life can amplify their original voice.

The opportunity to write a letter or create a document about one’s own beliefs and ideas is a freedom that gives one the respect and ability to preserve their own stories that they are entitled to. Being trusted with the responsibility to hold materials that are considered precious to others has shown me how easily stories can be lost when not given the patience to evolve. The act of archiving is restorative and gives control to the storyteller. The ability to capture the essence of who a person is based on their own creation of writing or artwork evokes a more personal connection. This allows the person to be heard in new ways.

This process has changed how I see my personal letters and items from childhood. I once thought of them as clutter and relics of a self I had outgrown. But looking back, I can see them as evidence that memory can be a kind of valued art. The old Justice tank top I would wear every day in third grade reminds me of the endless playground adventures I would take on, from monkey bars to slides. A sketchbook filled with uneven self-portraits reminds me of the worlds I would face in my head, usually reflecting whichever Disney Channel show I was obsessed with at the time. These objects don’t feel like past relics, but instead conversations I continue to have with myself through different mediums. Each document acts as a version of me that is stuck in the past, but still informs who I am. To archive one's life is to trace between the past and present, always in dialogue with our own past.

When I see the shelf at home, those childhood artifacts feel vivid, resisting being sealed off by time. They are not static memories, but living archives. Like those who are unable to amplify their voices because of confinement, I am learning to speak with those same fragments of who I was to guide who I will be.

Maybe what it means to learn from preservation and reimagination is to understand that stories don't end where they are confined. They are able to expand and adapt. The archive is never truly finished because, as a living artwork, it teaches us how to understand the past while leaving room for what continues to be revoiced. What we learn from preservation is the ability to recognize what we hold, whether it be scribbled notes or photos, and continue to tell a story if we take the time to listen.

~~~

Some of the items in my current personal archive:

Prayer ring - worn everyday and everywhere, this gold and metal ring is a personal fidget gadget that holds the weight of my unspoken wishes.

Sony ZV-E10 - with its lenses scratched, my camera catches the light to preserve small moments of my environment and the people that fill up my life.

Black claw clip - always attached to my bag, holding my hair together when things get too overstimulating.

Beaten-up blue water bottle - dented yet persistent, the water bottle has been a part of every place I have traveled to.

Thrifted mixed-metal watch - this piece of jewelry, useless in its ability to count time because of its broken face, now measures the traces of its past owners and the moments of my present days.

Describing a continuity of experience, these archival pieces enable a meeting between my past and present. As I expand my archival collection, I hope to continue to carry these small reminders that who I was still shapes who I will be.