When my kindergarten class gathered on the rainbow rug each morning to recite the Pledge of Allegiance, I hid between the legs of my pee-wee classmates. Picking at the rhinestones on my friend’s Twinkle Toes sneakers, I watched the neon-green skinny kid squirm until our teacher gave him a red card. But when we were told to stand, everyone stood. As my five-year-old friends placed their hands on their hearts and pledged their devotion to the American flag like a nursery rhyme, my gut ached. The ritual felt mandatory. Nobody knew what it meant to pledge allegiance; we still had naptime.

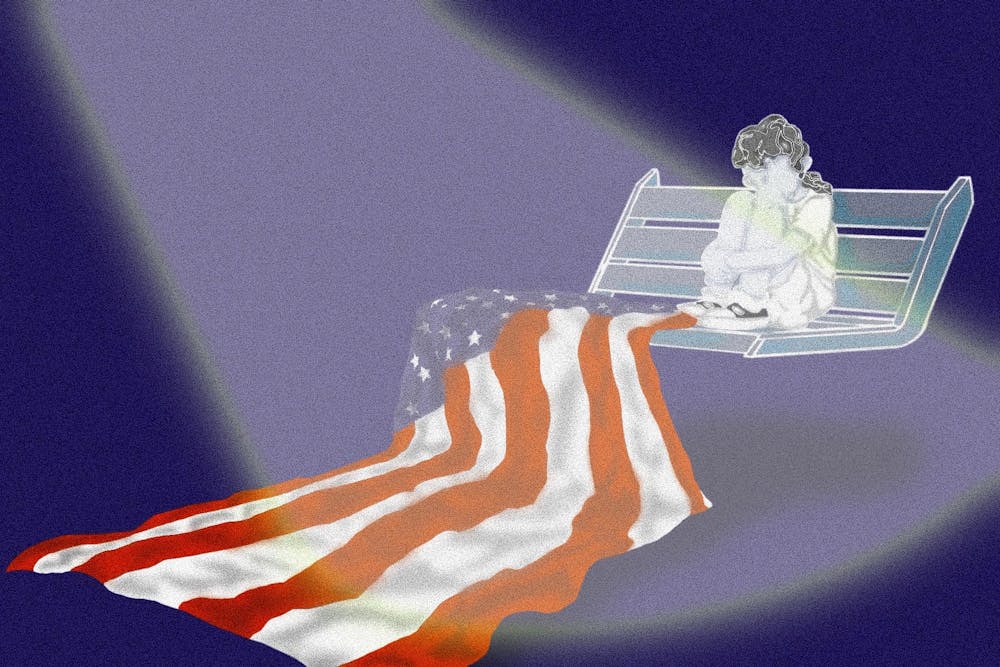

Enforcing blind ideological conformity in children feels like a bait-and-switch. In a nation more concerned with upholding civil liberties than protecting its people, the gun violence epidemic persists because America can’t see beyond the rose color: The Bill of Rights has become an alibi written for the perpetrator, not the victim. As a young person promised freedom and justice for all, I ask myself these days if patriotism is conditional.

My nationality has always felt especially important to me because I lack family roots. I didn’t grow up with either of my biological parents (a long and complicated story for another time). The promise that I could belong to a people—the American people—offered me a branch of shared history to grab onto. During elementary school in Woke-ville, California, I was excited to reenact Thanksgiving, to dress up as a Wampanoag Native American or a pilgrim, because I felt like part of a lineage. I didn’t learn until later how wrong I was.

But even before Columbus Day became Indigenous Peoples’ Day, if you had asked me what I thought a patriot was, I don’t think I would have considered myself one. Despite my love for my country, I believed patriotism was synonymous with nationalism: America first. I imagined hateful bumper stickers, booming election rallies, ostentatious campaign flags, the Second Amendment, and bigotry. When I finally learned the uncensored version of American history—as a genocide-perpetrating, slavery-enforcing nation that overpowered anyone who wasn’t a pasty Protestant—my understanding of the context grew to obstruct my longing to feel connected to my American heritage. Holding two opposing narratives—of profound belonging and profound exclusion—in the same hand felt like putting a Band-Aid on a gash. And so, my love of country became exclusively reserved for national parks, July 4, chocolate chip cookies, the Olympics, and the occasional interstate highway rest stop.

Since the shooting at Brown and the immigration crisis, my social media and news reels have been filled with a cacophony of voices struggling to grapple with tragedy. Videos of Brown students, headlines, hashtags, protests, and promises to never forget. I knew I shouldn’t watch, but my cognitive dissonance felt as if it was boiling over. Until finally, sense came breaking through. In January, I came across a video of former President Barack Obama speaking in 2015: During the funeral service for former state senator and Honorable Reverend Clementa C. Pinckney, Obama ended his eulogy by singing the hymn “Amazing Grace.”

Pinckney and eight others were killed in a shooting that took place at Emanuel African Methodist Episcopal Church in Charleston, South Carolina—one of the oldest Black churches in the southern United States. The full service lasted nearly five hours. Speaker after speaker took the stage in front of the ginormous congregation, giving speeches and sermons about the legacy of Black churches in America as spaces of refuge during slavery, and the redemptive power of love during terrible periods of loss. By the time Obama reached the podium, the room was remarkably joyful—greeting the first Black president, history galloped into the present.

Before he sang, Obama recounted Pinckney’s life as “a pastor and a public servant.” His remarks touched on faith, prayer, emancipation, racial justice, gun violence, and finally, grace. At the end of his speech, he said:

“It would be a betrayal of everything Reverend Pinckney stood for, I believe, if we allowed ourselves to slip into a comfortable silence again. (Applause.) Once the eulogies have been delivered, once the TV cameras move on, to go back to business as usual—that’s what we so often do to avoid uncomfortable truths about the prejudice that still infects our society. (Applause.) To settle for symbolic gestures without following up with the hard work of more lasting change—that’s how we lose our way again.”

These words inspired me, but I still felt angry. America failed. We failed. Continue to fail to protect our schools, children, and pledged values. I realized that the tumult and the outrage racketing in my mind was the best sign, perhaps even the only sign, that I loved my country desperately.

Instead of accepting pain as part of the American experience, my anger felt authentic. Or even the appropriate reaction to the unabridged version of American history and contemporary politics. Through the cloudy dissolution, I wondered why I consented to politics as they were, excluding myself from the room because I didn’t like how others expressed their patriotism. After years of chiseling away at American idealism, I realized it never existed in the first place.

At the end of his 35-minute remarks, the moment when Obama finally begins to sing is, to me, one of the most powerful moments in 21st-century American politics. To his immediate left, a pastor reacts first by saying aha!—an epiphany of the solution: In the face of the reflex for fear, there is also a reflex for unity. Spontaneous joy salves even the deepest wounds. Within moments, the entire congregation breaks into song.

When I returned to Brown last month to assist with spring orientation for a new batch of transfer students, we filled the heaviness with the only way we knew how: each other. The final day before classes began, Convocation was relocated to Faunce Arch, instead of the Van Wickle Gates. It was so cold that our fingertips burned; I expected the ceremony to lack luster because of the somber mood and location on campus, but as soon as somebody lifted a speaker, like a boombox trumpeting ‘70s disco, I teared up. Staff flooded out of University Hall to dance and cheer while the students ran with signs. Brown, too, found grace.

It feels wrong to tie stories of tragedy, particularly recent tragedies, up in a neat bow. I can’t write a conclusion to stories that will never be finished. But what I do know is to be a true patriot is to be a critic. On the eve of the American Semiquincentennial, my Americanness is defined by anger. United by a sense of urgency, the states of today and tomorrow ought to refuse to be blind. Broken pieces must be memorialized by something stronger than flowers and forgotten promises.