A newly approved medical implant — Bridge-Enhanced® ACL Repair — is providing an alternate treatment for Anterior Cruciate Ligament tears.

The current standard of care for ACL tears, which are among the most common knee injuries, depends on the condition of the injured person, according to the American Academy of Orthopaedic Surgeons. The surgical procedure, ACL reconstruction, replaces torn ligament with graft tendon — connective tissue between the muscle and bone that is taken from another part of the patient’s body or from a deceased donor, according to the Mayo Clinic.

“Reconstruction works very well for people but the joint never gets back to normal,” said Braden Fleming, Lucy Lippitt professor of orthopaedics at the Alpert Medical School and co-principal investigator of the preclinical trials of the study. “There's a lot of data that says those patients are still at risk for early arthritis.”

The BEAR implant, which was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last December, offers a surgical alternative to ACL reconstruction that may diminish arthritis risk, Fleming said.

“We hoped there would be a way to treat torn ACLs without having to damage another part of the body by taking a graft,” wrote Professor of Orthopedic Surgery at Harvard Medical School and the study’s lead investigator Martha Murray in an email to The Herald.

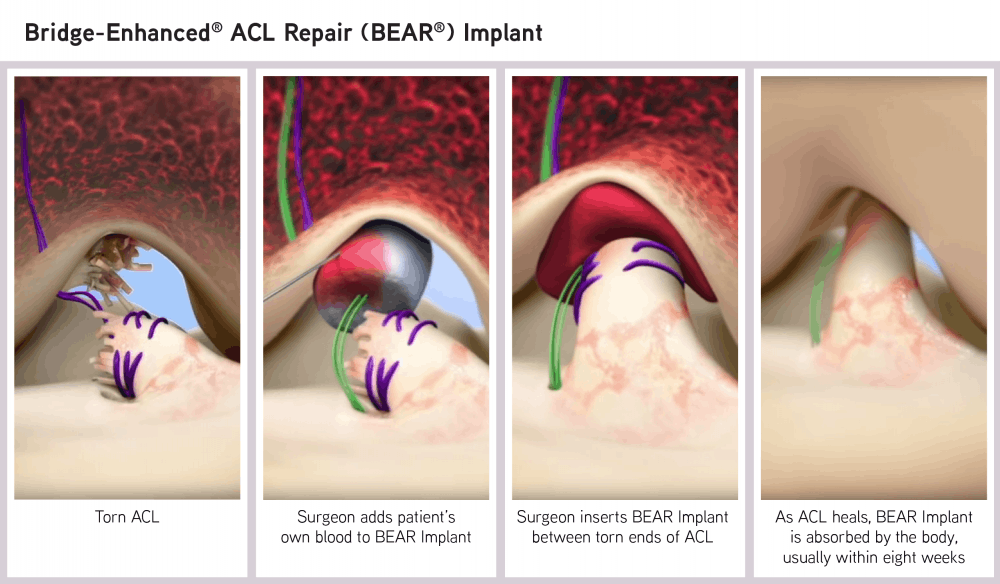

The newly-approved implant instead “restores natural anatomy and function of the knee” by “acting as a bridge between the two ends of the torn ACL,” wrote Miach Orthopaedics President and Chief Executive Officer Martha Shadan in an email to The Herald. Miach Orthopaedics is a company focused on developing surgical implants and is manufacturing the BEAR implant.

In this alternate procedure, the surgeon sutures the implant between the torn ends of the ligament and injects a small amount of the patient’s blood into it, according to the FDA announcement. Within about eight weeks, the implant “is absorbed and replaced by the body’s own tissue.”

The BEAR implant is the “first medical technology to clinically demonstrate that it enables healing” of the patient’s torn ACL, according to the Miach website.

Prior to obtaining FDA approval, the researchers completed preclinical studies in a pig animal model to provide an initial assessment on the safety and effectiveness of the implant. Since the scaffold uses a patient’s own blood to promote healing, the pig model was selected because its blood is very similar to human blood, Fleming said. These preclinical trials also allowed the researchers to refine the implant.

After showing safety and effectiveness in an animal model, the team obtained FDA approval for clinical trials, which began in 10 patients at the Boston Children’s Hospital in 2014. The researchers followed the health progress of these patients for three months to ensure no major side effects from the implant would occur.

Then, they received FDA approval to perform a randomized control trial at the Boston Children’s Hospital. They enrolled 100 patients, of which 65 were randomly selected to receive the BEAR procedure and 35 to receive standard ACL reconstruction. The patients’ health progress was followed for two years.

The researchers found that the two procedures yielded similar outcomes, showing that BEAR “was at least as good” as the surgical standard of care, Fleming said.

One of the most significant findings of the preclinical models was that “animals that got the BEAR procedure did not have much signs of arthritis (while) those animals with the reconstruction procedure had significant arthritis,” Fleming said. “But you can't prove that in humans in two years … so we needed to follow these patients” for a longer period of time, he added.

To do this, the researchers then conducted a cohort study of 50 patients mostly from the Boston Children’s Hospital and Rhode Island Hospital. It’s still “too early to say anything about arthritis (risk) or general outcomes” from this study, Fleming said.

A national multicenter randomized control trial funded by the National Institutes of Health will also soon begin at five sites, including the Cleveland Clinic and Rhode Island Hospital to compare the BEAR implant to ACL reconstruction.

The BEAR implant is currently not available in the U.S. or any other part of the world because of the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic, according to Shadan.

Once the implant becomes widely available, though, Murray hopes “the success of this procedure will help (researchers to) find better ways to get other tissues to heal better, including rotator cuff tendon and meniscus.”

ADVERTISEMENT