This year, President’s Day — Feb. 15 — came and went, as students trudged through the cold to make it to a day of classes typically designated a vacation day. Vacation will come a week later in the form of a four-day weekend.

As it happens, the long weekend from Feb. 20 to 23, so highly anticipated by students and faculty, is not technically President’s Day weekend. According to faculty government rules, the “fourth Monday and Tuesday of second semester” are always marked as off days.

The long weekend occurs four weeks after the semester begins to ensure students do not go back on break shortly after returning from winter vacation. “It normally falls when President’s Day is observed, but this year’s one of those calendar years where it didn’t,” said Robert Fitzgerald, university registrar.

The academic calendar is governed by a set of rules decided upon by the faculty government. These rules are fairly inflexible. A semester must be a minimum of 14 weeks, but including exam and reading period, it usually rounds up to approximately 15. There are a handful of holidays the calendar must incorporate, such as Indigenous People’s Day, Thanksgiving, Christmas and New Year’s.

These faculty rules regulate exactly when semesters begin and finish and when long weekends or recesses occur, but the calendar cannot predict any snow days that may arise during the winter months.

Should snow days occur, it is “up to faculty to make up for those days. … They can (assign) an extra paper or meet at another time on the weekends or (hold) an additional class,” said Karey Majka, assistant registrar for operations management.

Still, the calendar itself remains rigid. The University would be hard-pressed to extend the school year to make up for lost time because of Commencement and events taking place at the end of the school year such as Alumni Weekend, Majka said.

The faculty rules’ reliable formula allows the academic calendar to be released two years in advance. This enables family members and friends of students to make plans early when visiting Providence for occasions such as move-in day and Commencement.

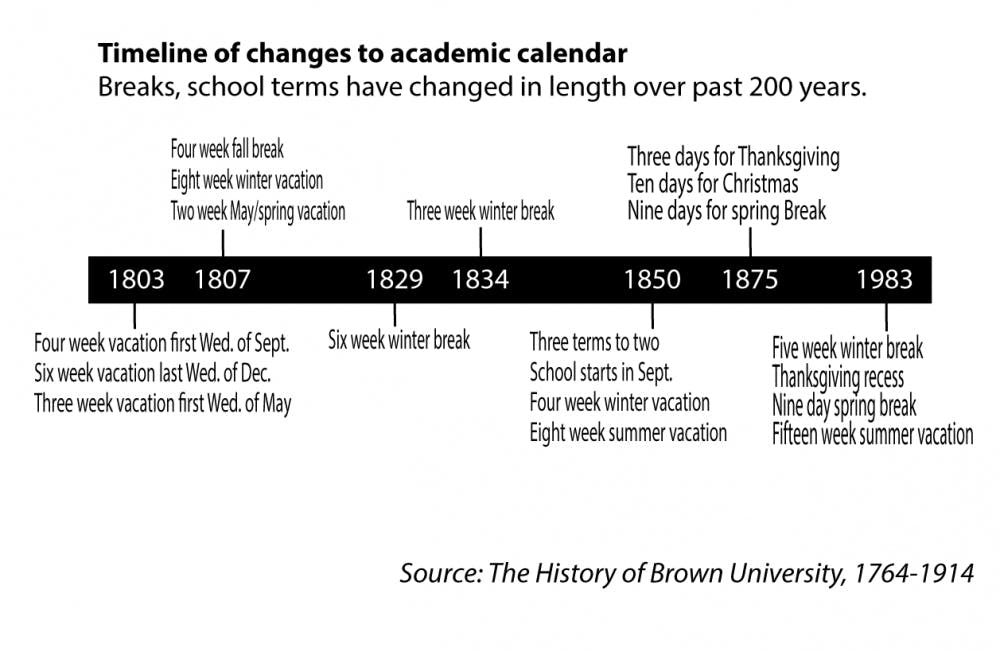

But for a set of regulations that seem so immutable today, faculty government rules — and the academic calendar they govern — have been dynamic over the years. According to Walter Bronson’s book “The History of Brown University 1764-1914,” students in 1807 lived by a very different calendar. Back then, the academic year was composed of three terms, including one held during the summer. Students had a four-week fall break that began the first Wednesday of September, an eight-week winter vacation that began the last Wednesday of December and finally a two-week spring break that began the third Wednesday of May.

In 1850, the three terms gave way to two. They lasted 20 weeks each and were separated by a four-week winter break and an eight-week summer vacation. In 1875, Thanksgiving recess was introduced, but Christmas break was only 10 days long.

Brown’s academic calendar took its current form in the fall of 1983. According to a September 1983 Herald article, that year marked a change in the academic calendar that shortened the summer break and extended winter break. The reform was largely student-initiated. Many students favored staying at home in December and January, enjoying an extended break between the two semesters.

But the change in the calendar was viewed with apprehension by certain members of the faculty. Then-President Howard Swearer thought the new calendar would be especially stressful for upperclassmen, who would be “surprised (by) the pace of the new calendar,” he said.

Indeed, before the reform, students were afforded a Christmas recess to study for exams. Therefore, they would have more time to prepare for the “post-Christmas crunch,” as it was described by the article. With this new calendar, the “post-Christmas crunch” arrived rapidly, leaving students no extra time to study. Certain schools, such as Princeton, still follow this model.

Today, while some students are still caught unaware by the madness of finals season, few remember a time when winter break did not last five weeks.