After months of designing, surveying and analyzing students’ reasons for dropping courses, a study conducted by the Office of the Dean of the College, the Undergraduate Council of Students and the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning fall 2016 revealed that only a small number of students dropped courses — most of which were dropped without negative impact on a student’s academic path.

Overall, only 933 courses — or around 4 percent of all enrolled courses — were dropped after shopping period, said Mary Wright, director of the Sheridan Center. In addition, most of these drops occurred at the end of the term or around the time of midterms, she added.

UCS approached the Dean of the College with the idea of looking at course dropping patterns in June 2016, Wright said. After researching similar studies completed at other schools and creating a survey, UCS and the Office of the Dean of the College collaborated with the Sheridan Center on designing and distributing the survey, as well as matching responses to registrar data for analysis.

The survey results largely matched University student demographics, said Marc Lo, assistant director for assessment and evaluation at the Sheridan Center. Students receiving financial aid and juniors were slightly overrepresented, while first-years were underrepresented compared to the overall number of students in these categories, Lo said.

Dean of the College Maud Mandel said that the underrepresentation of first-years made sense, considering how “just coming out of high school, first-years aren’t yet used to having so much freedom in determining their own paths” so they are less likely to drop classes.

The study indicated that many of these drops were made strategically and generally did not have a large impact on students’ broader educational pursuits, Wright said. Thirty-five percent of respondents had dropped a fifth class, and 16 percent of respondents had already foreseen dropping the course at the beginning of the semester.

“At Brown, with an open curriculum, you’re the architects of your own education, and students are very much acting in a strategic way,” Wright said.

But 34 percent of students noted that the dropped course was a prerequisite or requirement for their concentration.

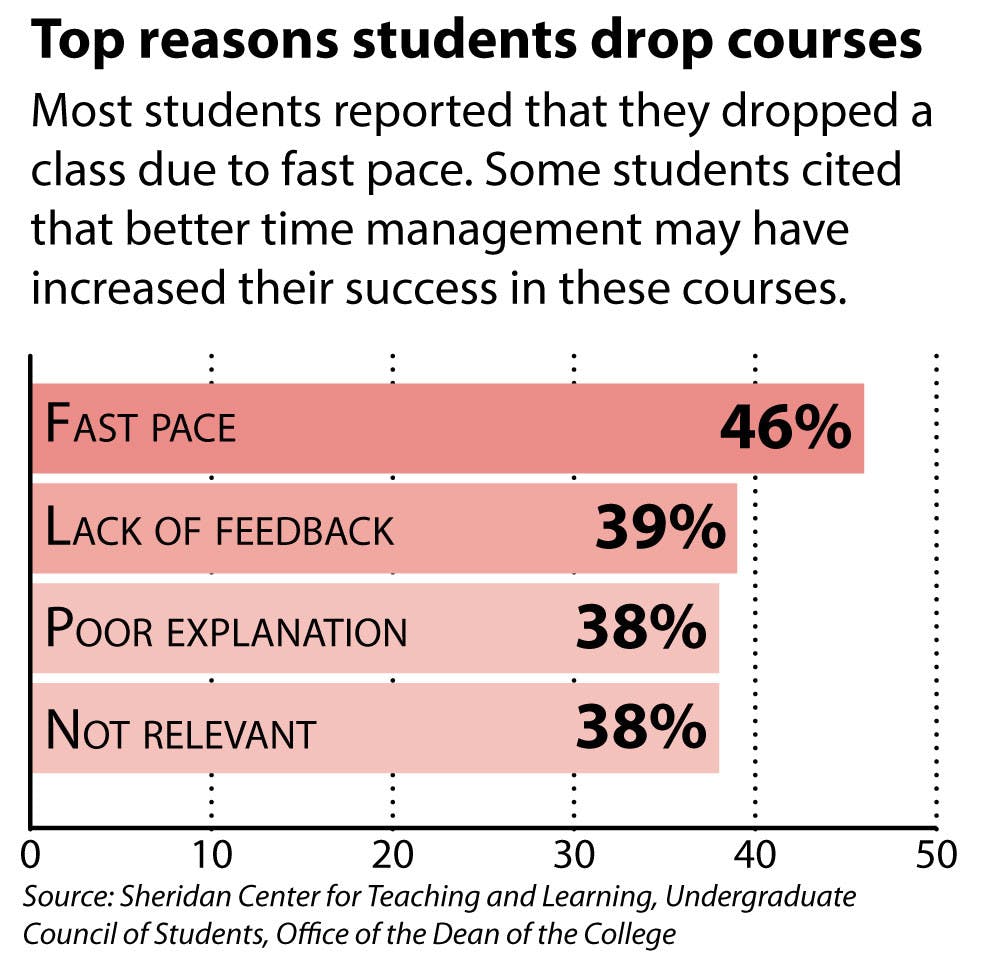

When focusing on these disruptive drops, the study found that the primary cause of drop decisions was course pace, a factor cited by 46 percent of survey respondents. Thirty -nine percent of students cited lack of feedback from professors on how to improve as their reason for dropping, 38 percent cited poor explanation of concepts and 38 percent cited perception of lack of long-term relevance.

In particular, pace was the dominant concern among historically underrepresented groups and first-generation students, Lo said. For those whose first language was not English, keeping up with reading could be a challenge, and a lack of previous access to resources and exposure to course topics for students from underprivileged high schools could manifest itself in this overrepresentation, he added. This reasoning also helped explain the overrepresentation of students receiving financial aid, Lo said.

Incoming UCS President Chelse-Amoy Steele ’18 suggested looking at how the course drop findings might align with benchmarks of the Diversity and Inclusion Action Plans.

The experiences of historically underrepresented groups in various departments will inform how we talk to faculty members or administration about improving course pacing, Steele said.

This data will continue to be utilized through departmental meetings with chairs and directors, where members of the Sheridan Center advise on positive faculty practices, Wright said. With larger departments, the Sheridan Center can also present data specifically tailored to the department, but this is not an option for small departments because of the importance of maintaining student confidentiality, he added.

As a teaching and learning center, the Sheridan Center is also integrating the findings into their own programs, emphasizing the need to offer peer-to-peer sections, encouragement of collaboration and timely feedback of regular assignments. To reduce further course drops, the Sheridan Center is focusing on addressing the four main causes: pace, lack of feedback, lack of clarity and lack of relevance.

Faculty have been “overwhelmingly receptive” to the results, with only three faculty members opting out of the study, Lo said. Many have been “ecstatic when finding out they’re doing particularly well.” For others who have more concerns, “they’ve already felt they needed to focus on particular aspects and the evidence helped confirm that,” Lo added.