In homage to the vignette-laden construction of a film I do not feel particularly inspired to pay homage to, what follows is a hodgepodge collection of reflections on watching Wes Anderson’s mass market art house movies, and why his latest stands unfortunately apart from the rest.

I was away, here in Providence, when I heard that the beloved independent movie theater in my hometown was in jeopardy of closing. Given that this was a theater of such local renown it had earned its own Wikipedia page, the closing was not a simple matter. There were articles written in the local paper and events designed to revive ticket sales. There were petitions for the city council to designate the theater as a historical site, thus sparing the imminent destruction of its velvet chairs and popcorn machines. There were even two protests organized on the sidewalk outside the theater. But none of it worked. Drained of an income during the COVID consumer slump, the theater closed quietly in March, and I have yet to return to observe the sorry state of its dismantling.

I never saw a Wes Anderson film in that theater, but sinking into those plush seats I developed a love for (or at least a general appreciation of) many of the actors enshrined within Anderson’s exclusive cadre of castmates. For my sixteenth birthday, a few friends took me to see Lady Bird, which—in addition to introducing me to the cultural phenomena of Saoirse Ronan and Timothée Chalamet—allowed us to revel in the artistic vindication of our youthful angst. With my brothers, I became acquainted with Frances McDormand as she delivered repeated tirades against the police in Three Billboards Outside Ebbing, Missouri. And next to my grandmother who swears she has seen every movie ever made, I’ve watched Tilda Swinton traipse across that curtain-framed screen more times than I can count.

Each time, I saw these films with other people: family, closest friends, classmates I had struck up random conversations with and decided to get to know better. And each time, the movies left an indelible impression on us, captivated as we were by the searing social commentaries, the beautiful scenes articulating poignant tales of trying to live, somewhere, somehow, in our fraught and ridiculous world.

To teach us how to write about stories, he chose a movie.

My ninth grade English teacher projected the opening sequence of Rushmore to explain to his group of artistically illiterate students how to write literary analysis. In lieu of diction and punctuation, we had the odd shots, the sweeping scene transitions, the frolicking classical music, and, of course, the close ups on characters and static fixations on scenery which render the whole image a misplaced painting. The exaggerated nature of all things Wes Anderson exemplified the evocative presence of style in literature, the power of literary devices which, even if we failed to fully understand their purpose, we could tell were obviously doing something.

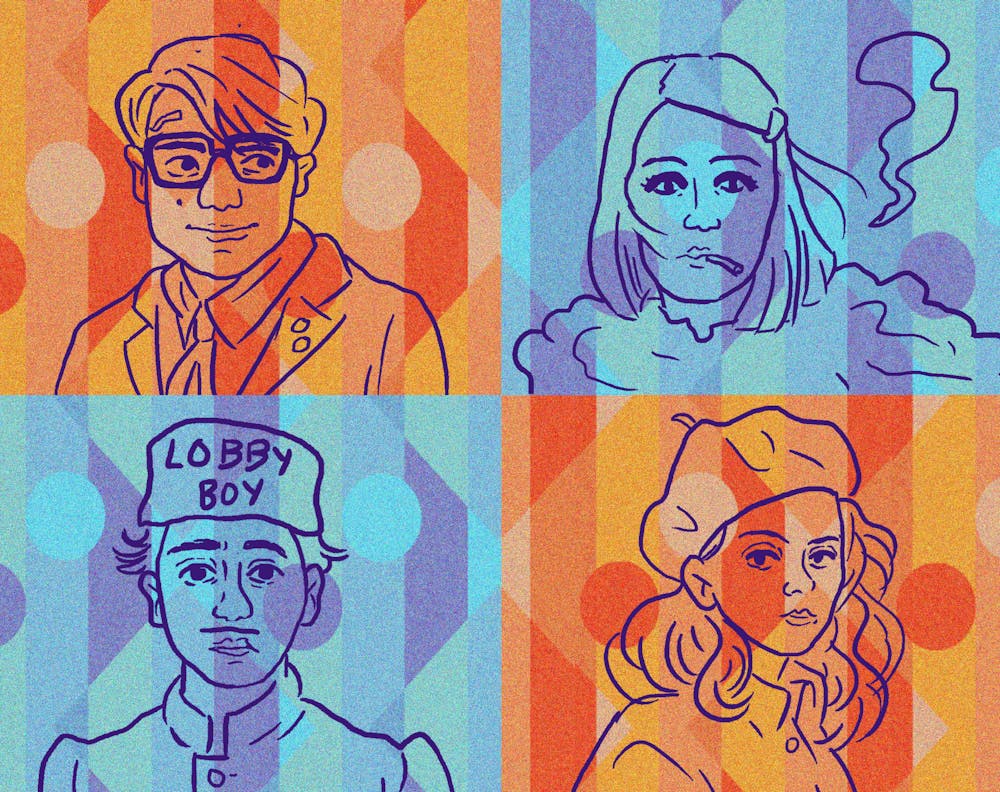

As someone who loves to make sentences twist along to trace the marks of my own brain, I appreciate the amiable quirk of the camera that lights up the scene and directs the plot of every Anderson concoction. His movies, with their endlessly eccentric structure, consistently cultivate an inimitable directorial voice. His quaint touch brands the scenes: kids perched cross legged atop a four-inch wide pole vaulted into the sky; camera shots that stare backwards into binoculars to look at the eyes of their owner; people marching over the flat profile of a mountain while still wearing their work uniforms; random sketches and cartoonized images and tableau shots scattered about without warning or explanation; Owen Wilson delivering exposition, while sitting on an stationary bike, while holding onto a moving bus tugging him through the streets, before inexplicably falling into a manhole. Each oddity adamantly endorses a surreal whimsy that defies logic, physics, or genre. Amid the violence and depression and morbidity that Anderson depicts with blasé flair, there is something vivacious and fun about the absurdity of a sad world where people are committed to strange jobs in strange places with strange people. The world is actually very weird, and burrowed within the shrouds of nonsense that is everyday life, there is just that—life, pulsing along to the beat of the story. That part is critical. In all the other movies of his I’ve seen before his newest, the absurdity tells a story.

Anderson’s most recent film, The French Dispatch, employs an abnormal film structure which, even as I acknowledge the fun of it, presents not so much an actual story as it does a creative class project with little potential for application in the real world. The movie celebrates the final issue of an eponymous literary magazine (a parody of The New Yorker) written by American expats covering the twentieth century social and political affairs of the fictional French city Ennui-sur-Blasé (Anderson imparting his ironic touch on a city of craziness). But rather than choosing a plot line to illustrate this, the film devotes its energy to acting out three of the articles included in the magazine. The frame narrative—the writers putting together the magazine—receives barely enough screen time to ground the movie on some cohesive plane, let alone to emotionally and convincingly reflect on the value of their journalistic project.

The French Dispatch relies on its mock literary article vignettes to impart a message, or rather an ode, to the craft it mimics: the immersive art of modern journalism. Journalism, the cast insists, is a process brimming with life, earning its idealized integrity by diving headfirst into the frenetic mess made by the societies that surround us. This may sound beautiful, and yes, provide enjoyable entertainment. But it’s merely a thesis justifying an industry. It is an essay, grasping at an earnestness conventionally communicated through fiction. It is an idea, segregated from some incontrovertibly compelling narrative woven into the scenery and the costumes and the dialogue that Anderson cherishes, the literary devices of the big screen left to stand alone with no story to depict, only an argument to articulate.

Which might be fine (sometimes people try to make apolitical art), if The French Dispatch weren’t so high profile. To consume the intellectual space and generate the artistic capital that it does, Anderson’s newest work, unfortunately like his past productions, chooses not to dedicate nearly as much intentionality towards resonating with the times as it devotes towards basking in the surreal wit of its own aesthetic.

Some viewers may appreciate the opportunity to simply forget the present, but I have never been attracted to art distracted from its own context. The social issues the movie mildly references are lost in the frenzy of running around in Ennui. This may be Anderson’s most diverse film to date, and yet one of my earliest reactions while watching was disappointment in how white it still presented, how fixated on the male sexualization of otherwise unknowable women. Tethered to the project of venerating journalism, these “diverse” writers and artists receive a few pieces of dialogue to justify their general role in the scene, but they exist deprived of the complete story that compels them in their work.

Recalling the power of the other stories acted out by Anderson’s illustrious actors’ circle, including his own previous films, the message asserted by The French Dispatch is lackluster. And for a movie directed by a man in love with all things visually energetic and abnormal, lackluster is the one thing that is actually weird.

Unlike with Anderson’s other films, unlike any other movie I can remember having seen in an independent theater, I ventured to the Avon and watched this one alone. The conditions reiterate the reality of the film. This was not a movie I would turn to when looking to forge a new friendship or to strengthen an old one. I might suggest it as some droll entertainment for a casual evening on the couch (or someone’s dorm bed), especially if in the company of fellow aficionados of this country’s most untouchable literary magazine. But its inability to show me my world leaves me without an artistic medium through which I can develop an abiding connection with someone else.

The French Dispatch is nothing more than successfully interesting. And interesting alone is not enough to orient two friends towards a shared understanding of ourselves.

My RPLs recently sent out an email inviting our dorm to go see a free movie together at the Avon next week. They told us that we will likely be viewing The French Dispatch, though it’s possible that the theater will have transitioned to screening a different movie by then. As much as I would find a second viewing enjoyable, I hope it’s something else. That way, maybe I will be able to get to know my neighbors better.