There are certain rules that you have to follow when you walk through an art museum.

Rule number one: you mustn't make any noise. In order to prove your reverence for the art, and so as not to disrupt others' contemplation, silence is a must. It is perfectly acceptable—expected, even—to throw a nasty side-eye at anybody who happens to have a particularly echo-y cough or unusually squeaky shoes. If looks could kill, then any poor soul who forgot to turn their phone on silent would be carried out of the Met on a stretcher.

Rule number two: distractions are strictly prohibited. No, you may not bring your American Girl doll. Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire has to stay in the car, and so do your Hot Wheels. No, you may not play Brick Breaker on your dad's Blackberry.

Rule number three: if you stop to look at a piece of art, you must look at it for at least 30 seconds. Any less and you start to seem downright arrogant—what, so you were able to soak up everything you needed from Van Gogh's tortured self portraits in all of a glance? Did you even attempt to tackle the color theory behind Jackson Pollock's "Male and Female?" If you struggle with this one, you can always have a staring contest with an old portrait. The painting will always win, and if your eyes water, at least you'll look like you've been profoundly moved.

These, of course, are rules invented by a little girl who always despised looking at the art in museums, for whom the propriety of an art exhibit made no sense, and therefore had to be committed to memory rather than learned intuitively.

I thought there must be something wrong with me. At age 10, I remember taking a day trip downtown to see an exhibit of Monet’s paintings. I wore my favorite Abercrombie zip-up and my beat-up Converse and stood fidgeting, ripping a Dum-Dum wrapper into tiny pieces in my pocket. I understood the technical beauty of the art: thousands of tiny strokes swirled together to form light-dappled clouds and vibrant flower beds. But the stir of emotion that I was supposed to feel looking at them—the innate fascination—was absent. Was I jaded? Ungrateful? My parents spent hours perusing every wall, reading every description. I could never understand how they moved so slowly. I tried desperately to copy their pace by counting: once you get to 20 Mississippi, you can move on to the next one. When this strategy became too tedious, I pretended to read the descriptions next to each painting, first in English, then in Spanish. My glazed eyes would move back and forth but not take in a single word. I committed to memory the color of each wall in every room I passed through. Black, gray, gray, green, gray, gray, green, blue, gray, gray.

I’d do anything to avoid the fact that I don't like to look at paintings. That truth would suggest some sort of emotional deficit in me, a lack of appreciation for beautiful things, and I wasn't willing to accept that reality.

One afternoon in late February, during my junior year of high school, I went on a school field trip with my French class to the Denver Modern Art Museum. There were thirty of us, all bundled up in parkas and beanies, hands in our pockets and shoulders huddled against the wind. We made our way out of the yellow school buses toward the museum, a hideous metal behemoth shaped like a little kid's attempt at a battleship.

Although my juvenile, stubborn dislike for art museums had calmed to a simmer, I still felt like an imposter. I was an actor among my earnestly enthusiastic peers, who chattered and laughed as we all trundled into the lobby. I settled into the back of the pack between two boys furtively passing a Juul back and forth and a quiet girl, Genevieve, whom I didn't know very well. She struck me as a fervently obedient museum-goer, with thick-rimmed glasses and a notebook clutched to her chest. I practiced repeating the rules in my head: be quiet. No distractions. Move slowly.

Our class was assigned a tour guide, dressed in a jewel-toned turtleneck and a long beaded necklace. She was soft-spoken enough that, in the back of the group, it was difficult to catch more than a few of her words at a time. I didn't mind. I had already resigned myself to an hour or two of quiet, absent-minded wandering anyway.

The first room we walked through was a long, wide, white-painted hallway lined with stone busts and full-body statues. The statues were meant to model human bodies, but with strange proportions: one had a head the size of a fist and a large, smooth torso; another was a triangular face with a long neck and spindly arms. We stopped by one statue that resembled a woman, with an impossibly thin waist and a massive bottom half that spread around her like a bag of sand. As I marveled at the strange sight in front of me, I heard a quiet voice, barely audible over the sound of the other students whispering and shuffling their feet: "can't say she ain't slim-thick, though."

I turned around and, to my surprise, found that the comment had come from Genevieve, the quiet, studious girl who was walking behind me. She was still the same—wearing a checkered cardigan, backpack straps tight, but now she had a small, wry smile. I couldn't believe it: The textbook representation of art museum propriety had broken rule #1, the Rule of Reverent Silence, within the first five minutes of our visit. I ultimately walked with Genevieve for the entire rest of the exhibit. We playfully critiqued the art and made each other laugh until even our seemingly unflappable tour guide told us to quiet down.

This moment may seem inconsequential, even mundane: what's more adolescent than a shallow joke in a museum on a high school field trip? But my experience visiting museums up until that point had been so rigid, so tight-laced, that I remember even now the profound effect that this visit had on me. I realized that perhaps the rules of museum etiquette that I'd committed so firmly to memory weren't helping me appreciate museums after all; they were making my visits less enjoyable. There is no reason why the rules that parents tell their small children to keep them well-behaved should remain the norm when they grow up.

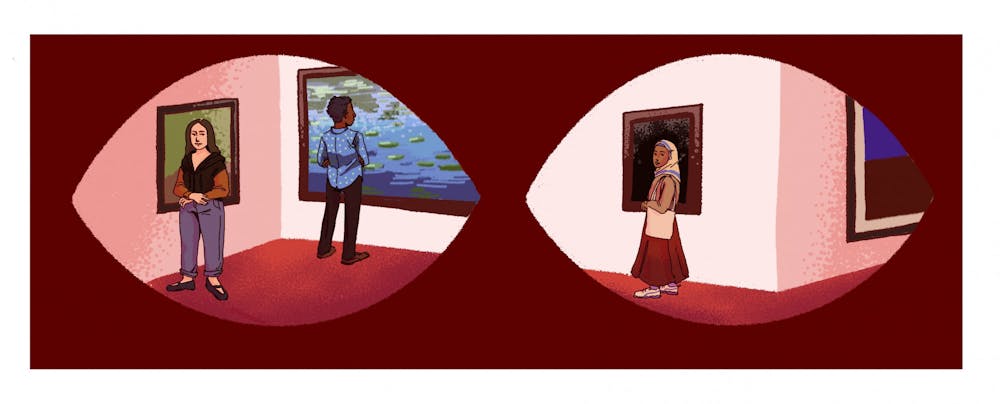

In general, the idea that museums are some sort of untouchable place with high barriers to entry, defeats the purpose. A museum is a way to remove the pretension from art, to take beautiful paintings and sculptures out of people's private homes and into the public eye. The excessive decorum reverses this effect: it transforms a would-be welcoming entryway into the artistic community and turns it into a rigid and stuffy environment.

So I say bring your book, listen to music as you walk through, make a joke to your friend about a sculpture you don't like. If art has one rule, then that rule is there are no rules, and there's no reason museums themselves should be any different.