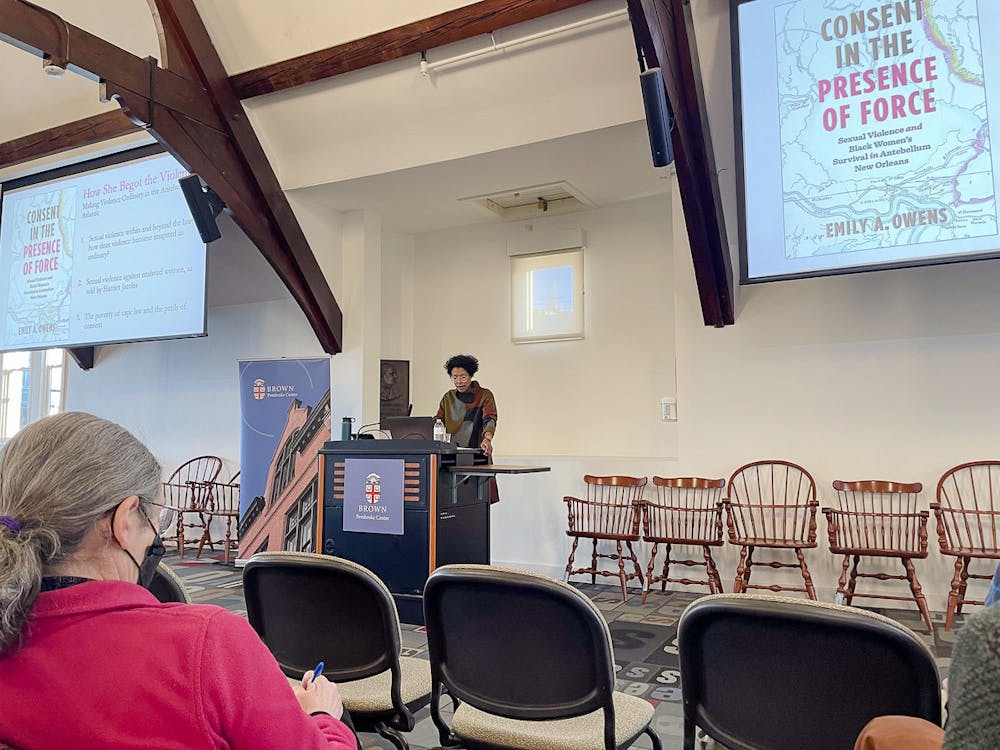

Emily Owens, professor of history, discussed the legal and ideological underpinnings of violence against enslaved women in a talk at the Pembroke Center Wednesday.

The event, titled “How She Begot the Violence: Making Violence Ordinary in the Antebellum Atlantic,” was this year's Elizabeth Munves Sherman Lecture in Gender and Sexuality Studies. According to the event’s website, the annual Sherman lecture features a distinguished Brown faculty member who works “in a wide range of disciplines” and presents “research that considers the impact of gender and sexuality across fields.”

Owens joined the University in 2016, bringing with her African American Studies PhD from Harvard and insight into how gender intersects with this field.

“Over time, I’ve become a historian,” she said. But “women’s studies and Black studies have really shaped the kind of questions I ask.”

Owens explained that the premise of her talk came from her first book, “Consent in the Presence of Force: Sexual Violence and Black Women's Survival in Antebellum New Orleans.”

The book “is a legal history that looks at the court cases of a handful of enslaved women who stood for their freedom,” she said. “It thinks about the context they were living in, the kinds of violence that they experienced and then tries to understand what legal architecture made that violence possible.”

Most of Owens’ book focuses on the lives of enslaved women who were situated in transactional sex. Owens said this includes “women who were working as concubines, in brothels and who were enslaved in those contexts.”

In her talk, Owens discussed the mechanisms by which sexual violence became engrained into American society in its first centuries.

She showed the audience excerpts from legal documents from states in the antebellum south, which defined rape as a crime that could only happen to white women. She then delved into the question of “understand(ing) whether and how violence changes shape relative to legal discourse, and if violence has a different meaning if it is not culturally recognized.”

Owens said that when writing these laws, lawmakers were reacting to violent social norms while also trying to “chart a world” where violence against Black women was not a crime.

“My research shows that the production of sexual violence against enslaved women as (not illegal) and culturally ordinary shapes the character of that violence,” she said. Consent, Owens explained, worked to legitimize sexual violence against Black women.

Owens specifically discussed the life of Harriet Jacobs, who wrote about her experiences as an enslaved person in her autobiography, “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl, Written by Herself.” According to Owens, Jacobs “provides the most extensive account of sexual violence and slavery penned by a woman” and is “the best legal theorist of her moment in helping us think about the laws that existed at the time.”

Owens discussed Jacobs’ relationship with her “owner,” who demanded that she consent to his desires under “threats of bodily harm.” According to Owens, the man insisted that Jacobs was indebted to him under a “contract” that existed between the two of them.

“The invitation to consent was” accompanied by a cycle of “request, denial, threat and acquiescence,” she added. “Jacobs’ narrative … points us to the terroristic landscape on which she traveled, where she would never be able to seek legal redress for sexual violence.”

“Persistence of consent in the sexual lives of women like Jacobs … points to the violent framework of rape,” Owens concluded. “If rape is a category that circumscribes the boundaries of violent sex, then consent is the category that insulates everything else.”

Wendy Lee, associate director of the Pembroke Center and director of the Undergraduate Program in Gender and Sexuality Studies, expressed excitement about the event’s high turnout, adding that “we had a great turnout of colleagues and students interested.”

Anna Brent-Levenstein ’25, who attended the event, called Owens’ talk “eye-opening.”

“I thought it was brilliant,” Brent-Levenstein said. “Critiquing the idea of consent from a historical lens … raised a lot of important questions.”