Fine! Fine. You got me, okay? I said all week that I wasn’t going to write a piece that started with two lines from a song that unexpectedly has deep and personal relevance to me, cut to some narrative, cut back to two lines from later in the song, rinse and repeat. But here I am. It works! I get it now, and I’m a fan.

Me not workin’ hard?

Yeah, right, picture that with a Kodak

Or, better yet, go to Times Square

Take a picture of me with a Kodak

I love this. It’s so bad. It’s Pitbull’s first No. 1 single, “Give Me Everything.” These are the first lines of his most famous song. If you were hearing Pitbull for the very first time, these would be the first ten seconds of your experience. This IS Pitbull. And it’s bad, right? We know this. He rhymes “Kodak” with “Kodak” without even burying it deep in a fourth verse that never gets airtime—nope, it’s at the very start. “Kodak” rhymes with so many things. Blowback. So wack. Show track. Okay, maybe none of those are good rhymes, but I never said I was Mr. 305. The point, though, isn’t whether these are good rhymes or not. It’s the phenomenon of it all. Pitbull has told you what he wants to say, and now he’s telling it to you again, almost verbatim. Almost.

What if it was verbatim, actually? What would that sound like?

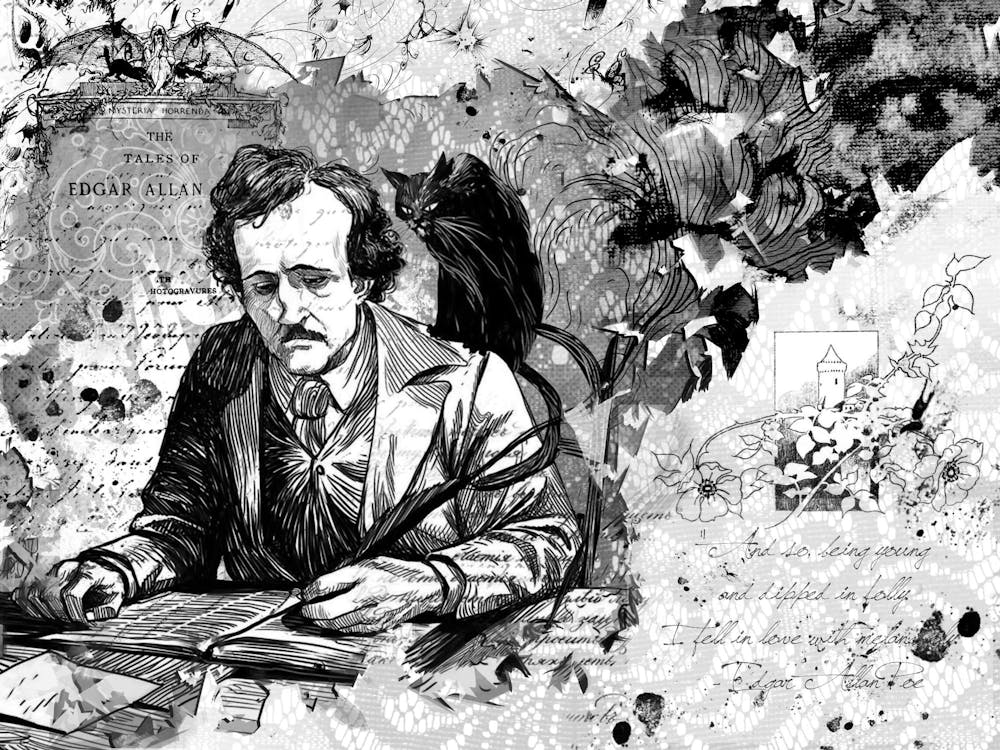

Mr. Mid-Atlantic, Edgar Allan Poe, wrote a number of poems that serve as examples. Fun bonus fact: Poetry is named after Poe. On the count of three, tell me the first thing that came to mind when you read his name. One, two, three: “The Raven.” Oh, hey! You too? Crazy. So. Poe’s first No. 1 hit single, 1845’s “The Raven,” is more similar to 2011’s “Give Me Everything” by Pitbull than you’d expect. Here’s the first stanza:

Once upon a midnight dreary, while I pondered, weak and weary,

Over many a quaint and curious volume of forgotten lore—

While I nodded, nearly napping, suddenly there came a tapping,

As of some one gently rapping, rapping at my chamber door.

“’Tis some visitor,” I muttered, “tapping at my chamber door—

Only this and nothing more.”

Poe uses “rapping” and “tapping” four times in just six lines. We hear the tapping, we have it described as rapping, the phrase is repeated, and then the narrator mutters this fact aloud. It’s a lot, and for me it entirely chokes the poem. Maybe my gripe with “The Raven” reveals my hamartia: I’m a worshipper of Mnemosyne, mother of muses, and in middle school I really thought I could memorize most of what you think of as the poetry canon. Reams and reams of poetry, at minimum. I’m still working on it.

I learned around seven stanzas of “The Raven” by heart—not quite the entire American canon, and not without struggle. Poe’s raven haunts the narrator with the “whispered word, ‘Lenore,’” but my raven muttered “rapping” and “tapping,” and later “chamber door,” incessantly. It would not let me be! I’m chugging along, reciting the familiar contours of souls growing stronger and imploring forgiveness, and then I splutter. Gently tapping? Faintly rapping? No, obviously, the adjective that comes later in the alphabet goes with the verb that comes earlier. Clearly, then, it’s “gently rapping” followed by “faintly tapping, tapping at my chamber door.” Pretty asinine mnemonics, I think. Poe does use internal rhyme in a generally pleasant, suspense-building fashion that I can appreciate, but my patience wears thin at times. In some Poe-ms, it feels like he left in two versions of the same line for the editor to cull. The editor never came.

“Ulalume” is a less famous Poe work, but it was the first one I ever read, and it still holds a prominent seat in my pantheon of spooky things. Poe skillfully weaves a world around the reader and pulls them along a dark path through forests of his creation, arriving somewhere deep and treacherous before they’ve fully realized what’s happened. It’s beautiful, glamorous, evocative:

The skies they were ashen and sober;

The leaves they were crispéd and sere—

It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year;

It was down by the dank tarn of Auber,

In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

Stunning, right? Poe lays out a big-picture description, a smaller detail of the scene, another part of the big picture, and a reason why that’s important too, just in the first four lines. Great stuff. It’s concise, immediately sets the scene, and already gives the reader key observations to chew on. “Ghoul-haunted”? “Most immemorial year”? I knew I was in for a treat. Reader, I’m so sorry, but what I just showed you isn’t actually the first stanza of “Ulalume.” Here’s what Poe really published:

The skies they were ashen and sober;

The leaves they were crispéd and sere—

The leaves they were withering and sere;

It was night in the lonesome October

Of my most immemorial year;

It was hard by the dim lake of Auber,

In the misty mid region of Weir—

It was down by the dank tarn of Auber,

In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

And it’s just not quite the same. Why do the leaves need to be “crispéd and sere” and “withering and sere”? Hearing Auber and Weir described twice in parallel to the same effect feels more like Poe is confused than writing intentionally. I like repetition, I like internal rhyme, but I get this little twinge of disappointment when I read “Ulalume” these days, wishing that someone had come in and just tightened it up a little. The argument Poe scholars make around this poem is typically that the repetition is in service of the poem being incantatory, almost hypnotic, and that the lines being repeated almost verbatim adds to the listener’s experience and sonic satisfaction. It doesn’t land for me. I try to recite it—not even from memory—and it just sounds garbled. Two-thirds of this stanza is direct repetition. Reader, please try reading this aloud:

It was hard by the dim lake of Auber,

In the misty mid region of Weir—

It was down by the dank tarn of Auber,

In the ghoul-haunted woodland of Weir.

I don’t find myself enchanted. There is a kind of droning hypnotic that I do understand, but if that’s what Poe’s trying to achieve, he should honestly go harder. The published version feels like it’s primarily quibbling with itself, like Poe wasn’t really sure what he wanted to write. This duplication is present in at least two lines in all ten stanzas of “Ulalume,” and it weighs it down. Maybe, then, confidence is what is missing. “The Raven” is confident in its repetition, frustrating as it may be for those of us trying to memorize it, and “Give Me Everything” is unabashed—Kodak does rhyme with Kodak, after all. I’m pretty sure Pitbull knows it’s bad, and “The Raven” is meant to be somewhat troublesome, but “Ulalume,” not so much. I enjoy the recitation of my abbreviated version of it far more.

I listened to more of Pitbull’s oeuvre for this piece, and found one more gem to leave you with:

Look up in the sky, it's a bird? It's a plane?

Nah, it's just me, ain't a damn thing changed

Live in hotels, swing on planes

Blessed to say, money ain't a thang

And he’s right. Plane rhymes with plane.