On the way to the appointment, they talk about their New Year’s plans. It’s December, and A is getting her tattoos removed. M is driving her because she is the only friend A trusts enough to witness the betrayal of her former belief in permanency. M also just likes to drive her places pretty often. The tattoos no longer represent her. They are both 22.

M parks in front of the kiosk a block away from the tattoo removal center. They get the classic: a blueberry muffin and a raspberry lollipop. M will give it to A after the appointment because A is brave. A faces things. One week earlier, they had argued over M refusing to wash her dead aunt’s shirt because she said it still smelled like her. A thought it smelled like dirt. M enjoys keeping old things. As they make their way from the kiosk, M confronts her:

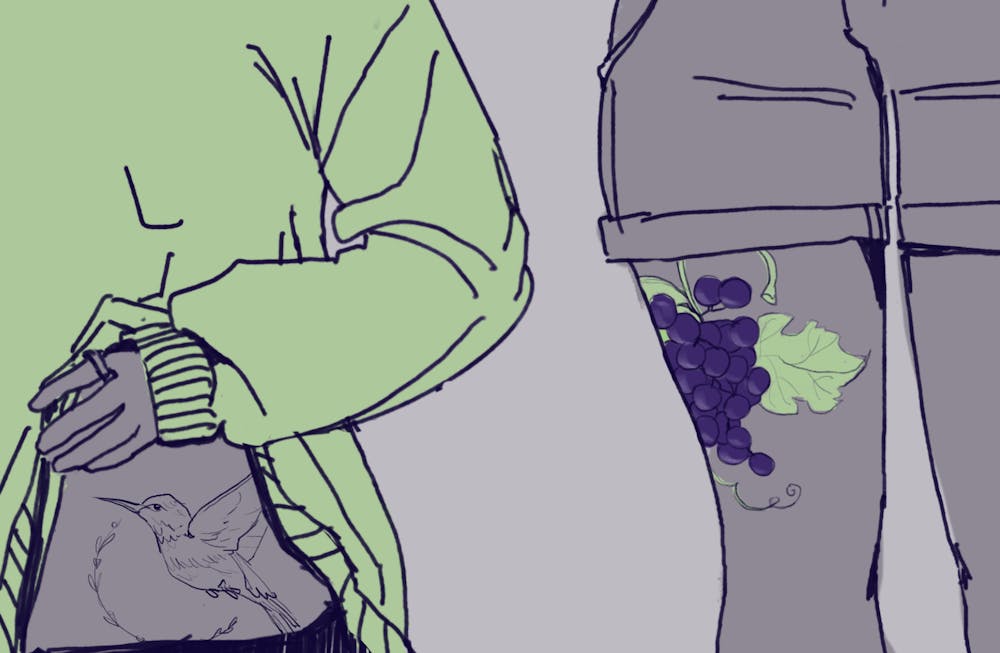

“This is what happens when you treat your body like a sketchbook. What do you mean grapes represent freedom?”

“It’s not that deep, M. My thigh-sized grape tattoo felt right when I got it.”

M offers a smile in contempt. She disagrees.

M only has three tattoos: her dog’s face on her shoulder, the title of her all-time favorite song on her wrist, and a moon matching her sister’s on her neck. She does not understand what makes grapes worth immortalizing.

“Do you see my point, though?” M asks A. “My wrist represents me. Every time I look at it, I’m reminded of something special.”

“Well, at least my grapes are simple. Memories can turn sour. What if your sister betrayed you?”

“It would still be less painful than getting laser every few weeks for not thinking about my choices.”

“Oh.” That stings.

It began with a sweater. A sweater, a feeling of warmth, a sense of comfort, a piece of joy. M remembers her lime green childhood sweater, her first favorite item. She remembers its replacement too, after outgrowing the first one, and how she pretended it was just as comfortable. It wasn’t. She remembers the hallway of her first home, walls full of framed family pictures. She remembers trying to remember the color of the frames after moving homes. She forgets whether they were beige or gray. She remembers her first best friend, her first crush, her favorite teacher. They are all gone now. M promised herself to keep her memories close. She wishes to make them stay.

M goes home after her conversation with A, wondering if she thinks too deeply about things. If her physical preservation of memories and feelings is counterproductive. If she is purposefully hurting A’s feelings to make her point. If her words sting more than the laser she was hoping to save A from. Her room greets her as she walks in, the same as every day: the smell of her vanilla candle, the unfinished yogurt bowl from the morning, the unmade bed, the half-opened blinds. She looks toward the picture of her with her mom and dad atop her bedside table and smiles. She hasn’t seen them in months. She walks over to the bookshelf and stares at her books. She can never decide whether to organize them by size, color, or alphabetically, and no option feels right enough. Still, she keeps them. One day, she will figure it out, she thinks.

On her walls, there are no empty spaces. Every movie, every artist, every song she’s ever loved—they’re all up there. She enjoys collecting objects too. Trinkets, magnets, lighters, pretty pens. Someone once told her that her room looks like “where the thinking happens.” She laughed. She enjoyed hearing that. There is no place for newness, but at least she’s not missing anything, she thinks.

M leaves her room and stops by A’s before stepping out. A’s room is right next to hers, and they like living together. A and M are best friends. A once told M she thinks they balance each other out. M said she hoped that was a good thing.

When M walks into A’s room to check if she’s back home, she is greeted by color. The decorations are so contrasting that they somehow complement each other. Some brighter, some darker, some smaller, some bigger, some modern, some antique. A changes her mind about them often. Change keeps the room fresh, she says, or something like that. M thinks she just hasn’t found anything she likes enough. A always leaves her flashing rainbow lights on by accident. Indeed, a room with color everywhere. A isn’t home, and M walks outside. She sits on her porch and smokes a cigarette. Two cigarettes. By the third one, she is crying.

Too much, she thinks. Too much.

M goes to get a tattoo on her own the next morning. On the way there, she revisits the elaborate justifications she plans to tell the tattoo artist. “Yeah, so it’s a bird from my favorite poem. A hummingbird, specifically. A good friend showed me the poem a long time ago, and it really stuck with me. It’s about birdwatching and the meaning of awareness and attention to detail and—”

What she actually means is: “I’ve thought enough about it to choose to carry it forever.” M takes pleasure in having her intellect and responsibility validated by professionals.

She’s in the waiting room, and A walks through the door.

“How did you know I had the appointment?” M asks.

“You put it on our shared calendar a month ago.”

“Ah.”

Sitting in the waiting room, they are the only two people there. They attempt to read the magazines that are available, but they are boring. A week ago today, they were over at a friend’s game night, and one of the games was trivia, and one of the questions was: “What three words describe you best.” M answered confidently because she loves these types of questions. A let the others answer. That night, A opened her journal and wrote: “Who am I.”

The next morning, M texted her before she woke up: “Curious, bright, genuine.”

It’s been 20 minutes and they are still in the waiting room. A is impatient, and she crosses and uncrosses her legs every eight seconds.

“So, what are you going to get?” A asks M, attempting to make conversation, but also out of genuine curiosity.

M just looks out the window. She knows A is expecting an answer.

“You should get an apple,” A suggests. “You know, since you like apples so much.”

M looks at her then, smiling. She can never quite tell if A is being serious. A can always make her smile.

“I am getting the entire handwritten letter that my grandpa wrote to my grandma the night before they got married, in his exact handwriting, all over my back.”

A looks M in the eyes, almost challenging her. She chooses not to say anything yet, in case M is being serious. There’s no way.

“God, A. I’m obviously joking,” says M as she sits closer to A, away from the window.

“You would,” A responds mockingly.

M rests her head on A’s shoulder then, and A hugs her with one arm.

“What if the bad is too bad?” A asks her. What she means is: “What’s the need to face everything in all its profoundness, risking some inevitable negativity? Why not be full of plain joy?”

M, staring at the center table, just shrugs. “This tattoo, this sweater, the trinkets, the frames, the posters—they are my own. It’s the act of thoughtfully choosing them that gives them meaning. I know who I am.”

“Never said you didn’t.”

M thinks A isn’t getting her idea. Or maybe she just isn’t agreeing with her, failing to understand her necessity for symbolic reconception. Either way, M thinks A isn’t giving the matter enough consideration.

M thinks she can out-think anything. A is not a complicated girl.

“Well, don’t worry,” A tells her, sensing M’s lack of response. “I’m sure your tattoos and all your object-reminders will remain positive memories.”

M thinks that’s not the point. I can never forget who I am.

M puts her hands in her pockets. In a way, A’s remarks, along with her affinity for simplicity, excite her. In a way, it gives her a strange sense of hope that there are other ways of thinking. She knows this. Disagreements are inevitable. So are regretful tattoos.

Just then, M’s name is called.

“I’ll be back out in 30?” she says to A, standing up from the couch.

“Okay.”

“Okay.”