Several strategic planning committees were created last fall to shape the long-term goals for President Christina Paxson’s tenure. The formation of one such committee — the Committee on Educational Innovation — underscored the University’s goal to lead in higher education in developing education techniques and philosophies, particularly in science, technology, engineering and math.

The University’s emphasis on improving science education builds on efforts undertaken in recent years and could reshape how introductory science is taught at Brown.

Experiments in education

Last summer’s version of CHEM 0350: “Organic Chemistry” bore little resemblance to the structure of the course during the school year. Rather than going to lectures, students attended problem-based workshops in the Science Center, tackling topics like tautomerization in small groups under supervision of teaching assistants.

The change developed after professors noticed that students enrolled in summer CHEM 0350 passed the second course on the subject, CHEM 0360: “Organic Chemistry,” at a lower rate than did those who took CHEM 0350 in the spring, said Andrew Silverman ’14, who has been an organic chemistry TA both during the summer and during the school year. Though lectures could conceivably work in the school year, they were less effective in the condensed summer schedule.

“The summer actually forced self-ownership,” Silverman said. “Students would sit at tables and literally have to work on a problem by talking about it dynamically. They weren’t passively engaged with the material like they would be in lecture. That’s something that’s just super important.”

Other courses in the near future will test non-traditional structures. This fall, the Sheridan Center for Teaching and Learning will pilot a discussion-based version of ECON 1110: “Intermediate Microeconomics,” The Herald reported last month.

Integrative classes specifically for students in the Program in Liberal Medical Education — which will launch fall 2014 — could help the University become a leader in pre-medical education reform, Associate Dean of Medical Education Philip Gruppuso told The Herald last month.

In 2009, the Association of American Medical Colleges and the Howard Hughes Medical Institute published a report emphasizing the need for integrative, interdisciplinary courses for pre-med students.

New approaches to teaching introductory science classes could help lower attrition rates in STEM fields, according to a 2011 report by the Association of American Universities.

For many institutions, “the focus of keeping students interested in science is a low priority,” said Mitchell Chang, a professor at the University of California, Los Angeles who studies trends in higher education. “So you have to raise that priority, and once you do, you start to shape your curriculum differently.”

While few institutions have restructured science curricula in this way so far, results look promising, Chang said, citing examples from the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and the California Institute of Technology.

“These classes are smaller and taught in a way with application to real-life issues,” he said. “But (students) are learning the fundamental knowledge in ways that the instructors intentionally apply to real-world problems.”

Curricular changes at Brown have been born of circumstance-specific factors — a compressed time frame in the case of summer CHEM 0350 — as well as ideological factors. Last fall, the School of Engineering broke ENGN 0030: “Introduction to Engineering” into smaller problem-based sections, significantly reducing the amount of time spent in a large lecture, The Herald reported at the time. The change was motivated by an increase in enrollment and student feedback.

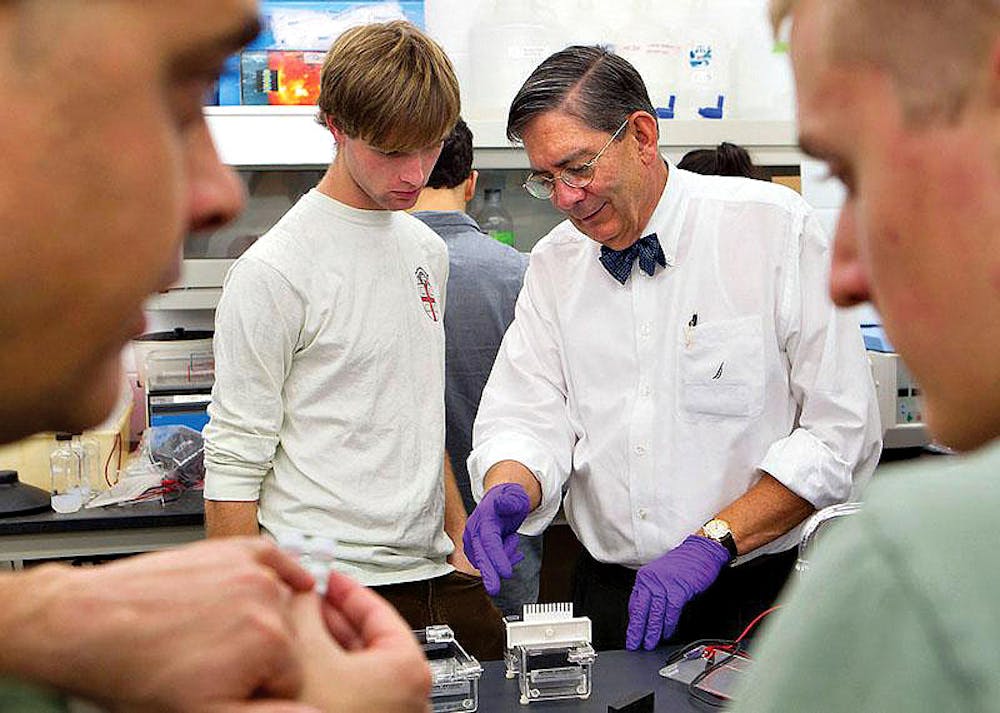

New biology courses have emphasized lab work and hands-on learning. In 2011, the University introduced the year-long course BIOL 0190R: “Phage Hunters,” in which first-year students isolated viruses and analyzed their DNA, participating in active research while learning introductory lab techniques, The Herald reported last year. Though the class was designed and funded by the Howard Hughes Medical Institute, Associate Dean of the College for Science and Director of the Science Center David Targan told The Herald at the time it could potentially be retained at Brown in the long term.

“Having that much more visceral experience using all the senses — it’s impossible not to be engaged in it, whereas it’s easy to zone out in a lecture,” Targan told The Herald last year. “There’s just a lot of evidence to show that that’s the best way people learn and the best way to keep people interested.”

Multiple pathways

In its interim report published January, the Committee on Educational Innovation outlined several proposals for developing science pedagogy, advocating new introductory courses, interdisciplinary initiatives and integrative pre-med courses like the one being piloted this fall.

“We have to continue to develop new ways to reach all of our students,” said Dean of the College Katherine Bergeron, who is chairing the committee. “We need a variety of pathways.”

One way the committee envisions this is through an array of “Gateways to Science” courses in each discipline, which would introduce students to STEM disciplines through hands-on classes focused on real-world problem solving, according to the interim report. Other introductory classes that emphasize data analysis, computer programming and scientific literacy could offer additional entry points into the sciences.

By pairing courses that deal with similar topics in different ways, the committee hopes to get students “really thinking about knowledge and thinking about the ways in which different disciplines are tackling the same questions,” said committee member Peter Johnson ’13. Under this system, students might enroll in two courses — an archaeology course in the fall and a materials science course in the spring, for instance — that facilitate discussion of issues relevant to both fields.

“Obviously that would take some faculty resources,” Johnson said. “It’s not like co-teaching, but it would take collaboration outside of the department.”

Though not explicitly addressed in the committee’s report, innovation will be tied to the question of online education. The University will pilot online courses this summer, and a separate strategic planning committee convened last semester to examine how online education might influence Brown’s future.

Limited resources

But committee discussions of the University’s future were not influenced by questions of its resources, Johnson said. Evaluating feasibility remains a task for Paxson, Provost Mark Schlissel P’15 and the Corporation over the next several months.

But given the resources currently available — manpower and space being chief concerns — dramatic curricular reform is not possible, said Robert Pelcovits, professor of physics.

Though it would be “ideal” to integrate more problem-solving elements into classes, “it’s just not feasible,” said Sarah Taylor, instructional coordinator and science learning specialist at the Science Center, who co-taught organic chemistry last summer.

Adopting the summer format of organic chemistry for the academic year would require a substantial number of TAs, Silverman said, adding that the number of TAs recently dropped from 14 to 6 due to funding constraints.

Large-scale changes can be costly in terms of space. When MIT launched a technology-assisted effort to make introductory physics more discussion-based, renovating two classrooms to make them conducive to discussion cost $3 million, according to the project’s website.

If it ain’t broke...

Concerns with introductory science courses can largely be addressed with small-scale changes, many instructors said.

Though smaller classes are often seen as better, there are “enough exceptions to that rule,” Targan said. Students who work to establish relationships with professors can benefit greatly even in a lecture class, Targan said, though it is the student’s responsibility to forge that relationship.

Jan Tullis, professor of geological sciences who co-teaches GEOL 0220: “Physical Processes in Geology,” said drop-in hours are important for success in her class. Rather than simply answering questions, Tullis said she aims to “coach and guide” her students.

As a coordinator for group tutoring and other resources in the Science Center, Taylor said she has found many students do not seek the assistance they need.

“They’re used to being successful academically because that’s why they’re here,” Taylor said. “A lot of them are reluctant to look for help. They think they’re self-sufficient or that they should be self-sufficient. So they are reluctant, embarrassed, ashamed — I’m not quite sure what it is.”

Targan cited iClickers — remotes students use to answer multiple choice questions with the results immediately tabulated on the instructor’s computer — as effective teaching tools in large introductory lectures.

iClickers provide “more opportunities for the instructor to understand much earlier in the class period what people understand,” Targan said. “It used to be that you could actually go for weeks and then have your first test … and realize that people were lost.”

But iClickers may not be enough to make a class feel more intimate, said Victoria Ferreira ’14, a pre-med student. “I don’t think using an iClicker was that helpful at all. It just made me pay attention for the first 20 minutes until (professors) asked the clicker question.” Ferreira added that it can be “super intimidating” to ask a question in a class with hundreds of students.

Varying the types of assessments can also solve many concerns, Bergeron said, citing research-based writing assignments as alternatives to exams.

‘Too big to ignore’

Identifying alternative forms of pedagogy in introductory STEM classes is critical for the nation’s growth, according to the 2011 AAU report, which states that scientific literacy is vital for both science and humanities students.

“A lot of places are going to be experimenting,” Johnson said. “And there’s a lot of federal funding out there for people who can ‘solve’ these issues in higher education today. And it’s kind of too big to ignore them.”

Given its desire to be at the forefront of educational innovation, the University must move carefully, Johnson said.

There is “an understanding that if we move too fastidiously into one area without really seeing — without really testing and seeing its effects — then that’s a bad thing,” he said.

Johnson said he does not think the University will heavily favor one model of education over another and will instead opt for a variety of approaches.

Bergeron said she envisions the curriculum being adapted gradually, as pilot initiatives are scaled up.

“It’s quite possible that looking down the road 10 years … there could be other modalities that help to transform the idea of the large lecture so that students could be working in more lab-like settings, discussion-based lab-like settings,” Bergeron said. “Maybe the idea of the entry-level science course could actually reverse itself, so that the lecture became less of the focus and the lab became more. But that would mean reorganizing the way we currently do things.”

-Additional reporting by Jessica Brodsky, Phoebe Draper and Kate Nussenbaum

ADVERTISEMENT