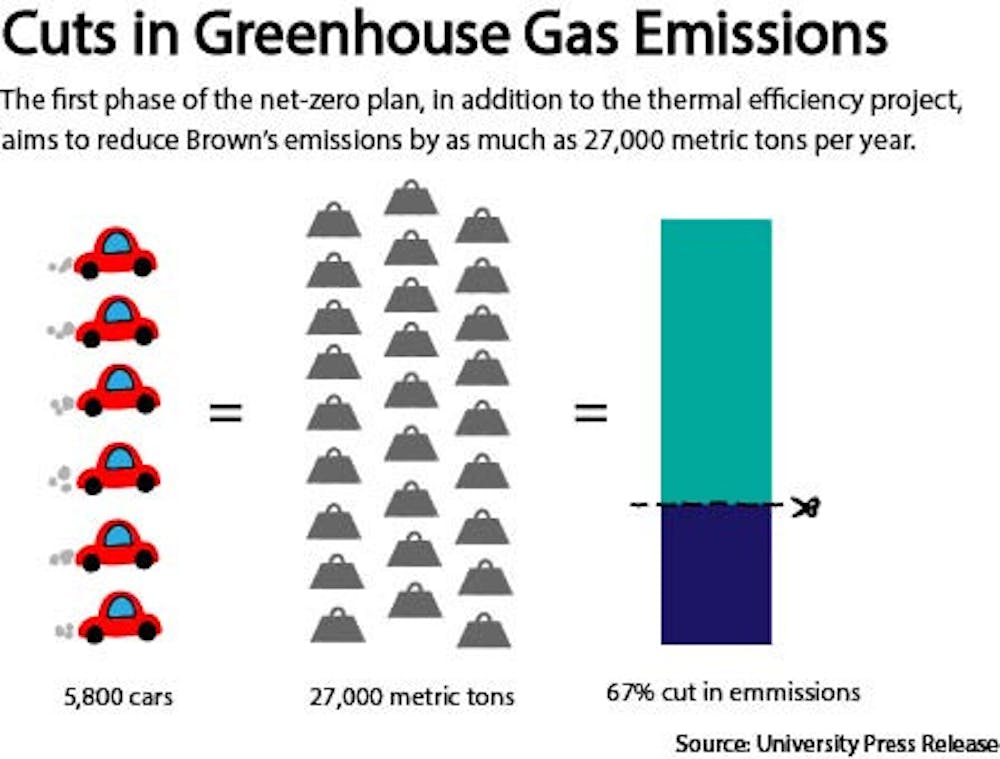

The University plans to reduce its campus greenhouse gas emissions to 75 percent below its 2017-18 levels by 2025 and achieve net-zero emissions by 2040, a Feb. 11 press release stated.

The new “aggressive” emissions goals were approved Feb. 9 by the Corporation, the University’s highest governing body. The University’s net-zero plan is “technically and financially feasible,” said President Christina Paxson P’19 in the announcement. “Taking into account money saved through the purchase of lower-cost electricity and efficiency improvements in the central heating plant, the net-zero plan is expected to cost less than $1.43 million per year in additional expenditures from 2020 to 2038,” the press release stated.

These expenditures are in addition to the $3 million per year that the University already spends on campus upgrades to reduce greenhouse emissions, wrote Stephen Porder, assistant provost for sustainability, in an email to The Herald.

The four-phase plan is already underway. Phase one started with two University-sponsored clean energy projects that are expected to offset 100 percent of on-campus electricity use, The Herald previously reported.

The net-zero plan differs from plans at some peer institutions because, rather than relying solely on buying clean energy offsets, it “depends on real changes in (campus) infrastructure” and consumption, Porder wrote.

During phase two of the initiative, which is scheduled to begin in 2022, the natural gas fuel source for the University’s central heating plant will be replaced with “post-consumer bio-oil” — oil that has already been used in food preparation and recycled — said Leah VanWey, associate provost for academic space and professor of sociology and environment and society.

This project “will reduce our dependence on fossil energy dramatically,” Porder wrote. It is expected to reduce campus greenhouse emissions by “an additional 10,000 metric tons” per year, according to the announcement.

The initiative’s third phase is a long-term thermal efficiency project. The University’s central heating network — which heats approximately 70 percent of campus facilities — and the buildings connected to it will be renovated to lower energy consumption for heat. The University currently uses steam to heat parts of campus, and the renovations should allow for a switch from steam to hot water in addition to lowering the necessary hot water temperature, VanWey said. At the moment, facilities is working to reduce the water temperature to 250 degrees Fahrenheit and begin using liquid water instead of steam, but the ultimate goal is a reduction to 185 degrees.

This larger reduction in temperature will require substantial changes to campus infrastructure, which should take place between 2021 and 2038. In order to minimize disruption to students, the renovations are scheduled to occur mainly during summers “when heating isn’t needed,” and when there are fewer students on campus, VanWey said in the announcement.

Heating systems for buildings that are not connected to the central heating loop will be individually renovated. If renovation is not possible, the buildings’ emissions will be offset with renewable energy purchases, the announcement added.

The fourth and final phase of the initiative will involve the conversion of the University’s central heating plant to a renewable, “non combustion–based” heat source, Porder wrote in an email to The Herald. This phase is scheduled to take place in 2038, the announcement stated. Currently, the best replacement would be “air source heat pumps with bio-oil supplement for the coldest days,” he added.

The University also recognizes the need for a “flexible” plan that allows for change as technology advances, VanWey said. “If new technology becomes available by the time we’re done with these renovations, we can use it,” Porder wrote. Regardless of the final heat source, “the work that we’re doing in the buildings that makes (them) accept lower-temperature hot water will … (increase) the efficiency of the central heating plant,” VanWey said. She is also scheduling “regular reviews of (the technology) … with the Corporation as well as with the internal leadership” at the University, she added.

Since 2007, a number of energy efficiency projects have been enacted on campus to reduce emissions, such as thermal efficiency upgrades, the implementation of LED lights in University facilities and the conversion of the central heating plant’s fuel source from oil to natural gas, VanWey said. The University’s previous emissions goals included reducing “on-campus greenhouse gas emissions by 42 percent below 2007 levels” by 2020, The Herald previously reported. As of fiscal year 2018, greenhouse gas emissions are “currently standing 28.2 percent below 2007 levels,” according to the University’s 2018 sustainability report.

VanWey could not guarantee that the University will meet its 2020 emissions goals because one of the two planned offset projects must become operational in order for those goals to be achieved, she said.

The planning of the net-zero initiative began fall 2017 and lasted 18 months, according to VanWey and Porder. The two co-chaired a committee charged with “developing long-term greenhouse gas emissions goals and … sustainability goals for the University,” VanWey said.

The committee employed the services of three consulting firms, according to Porder. They reviewed the efforts of peer universities, the University’s own progress and what would be financially and logistically feasible “in order to take a leadership position” in combating climate change, VanWey said.

Porder is “very confident” that the goals of the new net-zero plan will be achieved. “For something this important, I have no doubt we will follow through,” he added.