When Brown University students woke up on the morning of Oct. 8, 1918, they learned they had two choices: pack up and return home or remain on campus indefinitely. A campus-wide quarantine was being imposed, due to the growing threat of a raging strain of influenza.

Armed guards were stationed at the gates of campus and outside the John Hay Library. Anyone who needed to leave or return to campus had to have a pass from the administration. Downtown Providence was strictly off limits.

The Herald detailed the University’s plan: “The entire army and navy units will be incarcerated in the dormitories and as many civilians as possible will be quartered in the Alpha Delta Phi and Phi Gamma Delta fraternity houses.”

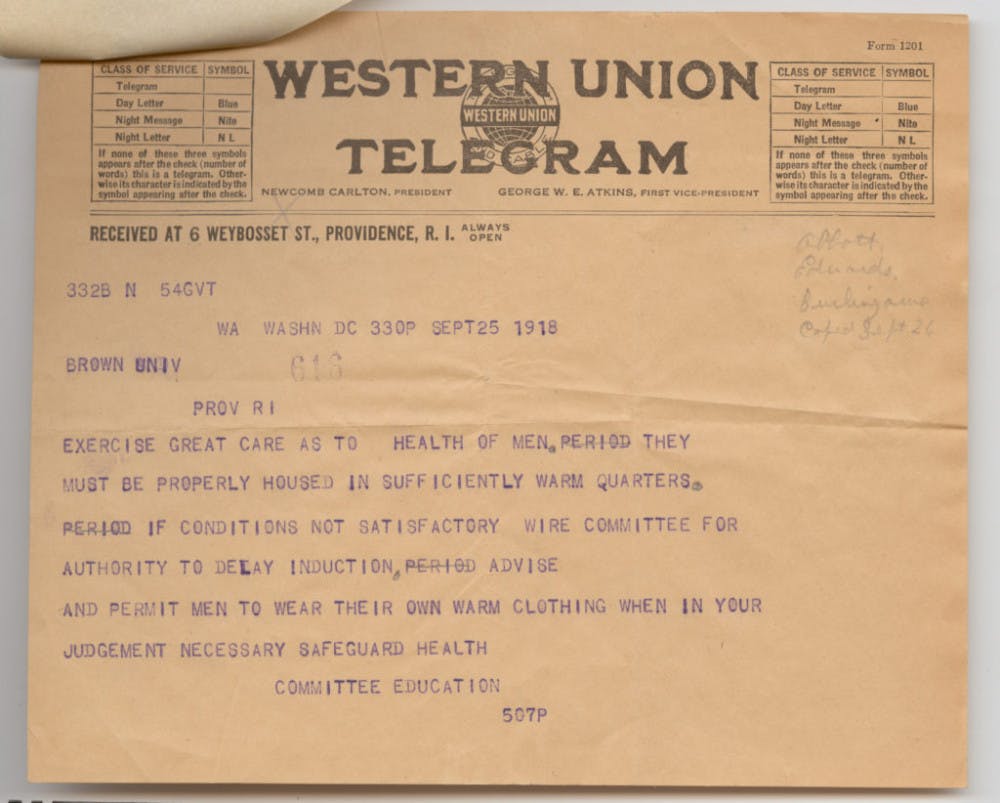

A telegram had reached University officials from Washington almost two weeks before. “Exercise great care,” it began, in blue-purple uppercase letters. It was from the Education Committee, and instructed the University to ensure suitable health safeguards were in place in preparation for potential disaster.

[caption id="" align="aligncenter" width="650"]

This disaster was the Spanish flu. It would go on to kill more Americans than World War I, World War II, the Korean War and the Vietnam War combined. There was nothing Spanish about the lethal strain; it ran rampant across the globe and soon touched almost every country on the map. Worldwide, at least 50 million people were killed.

The flu had arrived in Rhode Island by September 1918. Sailors in Newport first contracted the virus, and it soon spread to civilians.

In the weeks that followed, Providence Health Superintendent Charles Chapin, an 1876 Brown graduate, indicated that the virus had reached Providence and warned of an impending epidemic. But Chapin believed that there could be “no such thing as an effective quarantine in pandemic influenza.”

Still, when there were early calls to shut down the city’s theaters, cinemas and dance halls, Chapin refused, arguing that “the epidemic must run its course.”

Providence was slow to act compared to other towns and cities across the state due to economic concerns, said Catherine DeCesare, senior lecturer in history at the University of Rhode Island. “It was certainly recognized that it would impact the community economically to start closing down businesses and closing down social entertainment venues,” she said.

A century later, Rhode Island leaders have acted more swiftly. State-enforced social distancing, mask mandates and group-size restrictions were quickly commonplace across much of New England. Residents saw their work places close and their children home from school. On March 9, Rhode Island declared a State of Emergency. A stay-at-home order was issued in Rhode Island from March 28 to May 8.

But in 1918, as the flu spread, life continued as usual. On Sept. 28, despite mounting apprehension that sickness was festering, 3,000 people crowded into a theatre for a Liberty Loan Parade, a patriotic rally to encourage buying war bonds, DeCesare said.

The illness circulated through crowded communities. First the numbers rose slowly, then they soared — a trend that would be repeated 102 years later.

On Oct. 4, the state Board of Health met and, again, Chapin voiced his hesitancy at closing public spaces. But shortly after schools, theaters, cinemas and dance halls were ordered shut. Liquor establishments stayed open, DeCesare said.

[caption id="" align="alignleft" width="193"]

More than 2,300 people died across Rhode Island in 1918. October proved the cruelest month of all, with nearly 6000 residents falling ill in Providence alone. “No death has occurred in the student body, a fact which is indeed remarkable in view of the severity of the epidemic in the city,” The Herald reported Oct. 26, 1918.

Ultimately, one Brown University student and two students at Pembroke College would die from the virus, said Robin Wheelwright Ness MA’18, the senior library specialist in digital services within the University’s special collections. And of the 42 men listed on Brown’s Honor Roll (41 students and alumni and one faculty member who lost their lives in World War I), 22 lost their lives to illness, namely influenza-pneumonia.

Ness’s archival research work on the 1918 influenza meant she had been thinking about the University’s handling of a global public health crisis long before COVID-19 hit. But she could have never imagined how personally relevant this work would become.

Ness began sifting through documents, photographs and newspaper clips in 2015 as part of a broader project on the University’s involvement in World War I.

“The University was essentially a training ground for the army and the navy,” she said.

Strict regulations governed daily life for civilians and soldiers alike. All of the University’s dormitories had been transformed into barracks, each room outfitted with three or four sleeping cots. A rifle range was constructed in the basement of Sayles Hall. And Rockefeller Hall, now the Stephen Robert ’62 Campus Center, was turned over for a mess hall, accommodating about 600 men.

Unlike in the fall of 1918, when news broke of the COVID-19 pandemic a century later, Brown’s campus largely emptied. Of the 5,000 students that typically reside on Brown’s campus, only a few hundred remained. Libraries were locked, the chairs in the dining halls vanished, and hallways –– normally resonant with the sounds of life from within dorm rooms –– were silent.

When he wrote about the 1918 flu pandemic in Rhode Island in a Providence Journal article published this March, Tom Mooney was shocked by the scale of the lock-down efforts put in place by local and state governments.

“That seemed extraordinary to me,” Mooney, a visiting lecturer in English and a reporter at the Journal, told The Herald. “Now, in October, that’s just daily life.”

The number of reported COVID-19 cases in Rhode Island currently stands at 25,776; dozens more are added every day and at the time of publication, 1,126 people in the state have died.

Reminders of our new reality now appear all over, and in unexpected places. The occasional surgical mask or singular glove, missing its pair, lay discarded on the sidewalks.

In 1918, the quarantine on campus was lifted Nov. 4, just under a month after it began. It was viewed mainly as an inconvenience: “The shutting of 600 students into a small campus for four weeks is not conducive to effective study,” noted President Faunce. “Quarantine is hard on the boys.”

Providence’s physicians began to notice a resurgence of influenza in Dec. 1918 and early 1919, but it did not come near the devastation of Oct. 1918. In the months after the quarantine was lifted, the University continued under an unofficial quarantine, asking students to voluntarily stay on campus. Members of the naval and army units continued to be prohibited from leaving the campus without passes.

This fall, students returned to campus in phases; limited classes resumed in-person this Monday. But the path ahead for Brown, and the broader Rhode Island community, remains uncertain.

ADVERTISEMENT