By 2015, Brown students may have made a mark on space.

“Space has suffered from being something that’s only interesting to space geeks,” said Rick Fleeter ’76 PhD ’81, adjunct associate professor in the School of Engineering. A group of students is aiming to change that by building a micro-satellite — called a CubeSat — to help people learn about and experience space.

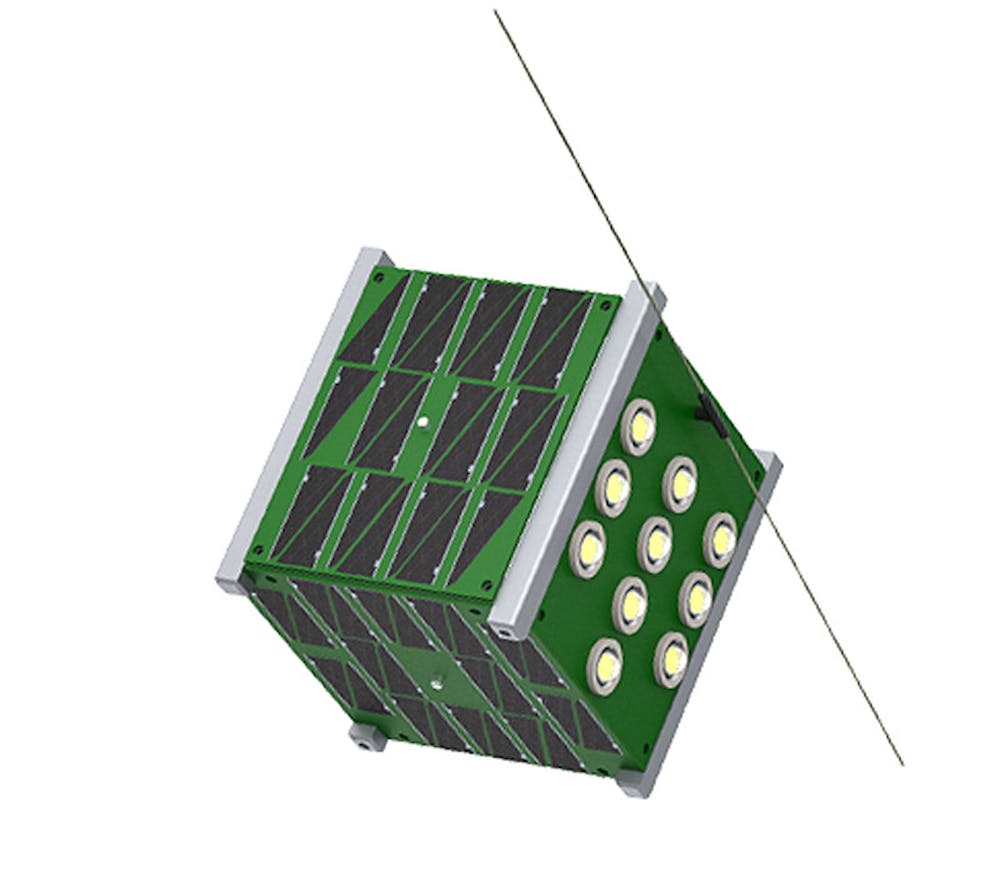

A CubeSat is a 1,000-cubic-centimeter satellite with a set of standardized requirements. Within two years, the team hopes to send its CubeSat, named EQUiSat, into space, said Hannah Varner ’14, one of the team’s current leaders. Herald Head Photo Editor Emily Gilbert ’14 is another of the group’s team leaders.

Preparing to launch

Founded in the spring of 2011, Brown’s CubeSat team grew out of ENGN 1760: “Machine Design” with Fleeter, a class in which the teams designed a space mission and built a piece of technology that could be used in the mission, said Alex Neff ’12, one of the team’s four founders.

“It started with an idea that our adviser had for quite some time. He’s been pondering this idea that space is becoming less of a fad after the Apollo missions,” said CubeSat founder Max Monn ’12 GS, a former Herald photo editor.

The group decided to continue working on EQUiSat as an independent study project in fall 2012, recruiting new members the following semester.

“We basically had one semester to make the group self-sustaining,” Neff said. Because the team members only had backgrounds in mechanical engineering, they had to learn the electrical engineering components of building EQUiSat, like figuring out how to wire a circuit, said Kelsey MacMillan ’12, one of the group’s founders.

It usually costs “millions of dollars to launch” a satellite, so students and smaller satellite initiatives cannot afford it, said Casey Meehan ’15, a current leader of the group.

Though CubeSats typically cost around $100,000 to build, the EQUiSat team is operating on a budget of $14,000, Varner said. The team has been able to function on this budget by building all of EQUiSat’s components completely from scratch. The group initially obtained funding from a University grant, which was then matched by the NASA Rhode Island Space Grant Consortium, Monn said.

The mission

Satellites “have a huge impact on your life,” which may not be apparent because they are in orbit in outer space, Meehan said. “When you go up over 300 kilometers in orbit, there’s a lot of data you can gather about Earth on a larger scale that can tell us more about ourselves.”

Team members hope to put in a panel of LED lights that will be visible to the naked eye from the ground as well as a radio that people on the ground will be able to hear when the satellite passes over them, Varner said.

EQUiSat could have uses in education as well. For instance, teachers might teach a lesson about space technology and the next night, their students could see firsthand “our satellite blinking through the sky,” Meehan said.

“Behind all the engineering intricacies, there’s a much more profound educational and social aspect,” Monn said. “It’s good to have a North Star outside of all the tech-y madness.”

The group documents the process on its website so that other groups can potentially learn how to build their own satellite.

Eventually, the team hopes to design “an interface to allow people around the world to interact with each other to see the satellite,” Monn said. This includes markers on a screen that identifies where observers have seen EQUiSat. “Even though you might be thousands of miles apart, you can both look up and see this little blinking beacon that was cobbled together by a bunch of college students,” Monn said.

Eventually “there could be a whole array of satellites, where every one would be like a pixel, and this array of satellites could make an image in space that would be visible from the ground,” Fleeter said, such as an image of the five Olympic rings.

The team currently has 25 members and is led by five upperclassmen. The team hopes to launch EQUiSat in 2015, Varner said. “We hope that (the team) will grow and be our mark that we left on Brown engineering,” Monn said.

A previous version of this article incorrectly stated that CubeSat is a 10-cubic-centimeter satellite. In fact, the satellite is 10 cm in length on each side, for a total of 1,000 cubic centimeters. The Herald regrets the error.

ADVERTISEMENT