For a number of undergraduates, Providence is the big city. It’s a place where you don’t know your neighbors. It’s a place where streetlights shine, sirens blare and cornfields are replaced by busy streets and fast cars. It even has a mall.

“Providence seemed a lot bigger when I first got here than it does now,” says Thomas Lutken ’14.

The Mississippi native is in the minority at the University, hailing from a small town where the word “brown” is no more than a color. His slow walk, anecdote-peppered speech, enthusiastic friendliness and “dumb phone,” he says, signal how sharply his upbringing diverged from those of many of his peers.

For the first four years of Lutken’s life, he lived in an old house without electricity or running water. When he moved to Oxford, Miss., a college town home to just under 20,000 people, it “felt like moving to a big city.”

“We got Wi-Fi in 2010 and it was a huge deal,” he says, laughing.

Coming to Providence, he was forced to acclimate to a fast-paced Northeastern social environment. Most of his peers are always in a rush, constantly checking phones and emails, he says. When Lutken sees acquaintances on the street, he has learned, they won’t usually stop to chat.

“In the South, where I’m from, if you ran into your second-grade English teacher, she would expect you to stop and tell her everything that had happened to you since the last time she ran into you in the grocery store,” he says.

Students like Lutken are a relatively small part of Brown’s campus population. They are underrepresented at the University, often hailing from communities that send few, if any, students to elite out-of-state institutions.

Administrators at private colleges and universities across the country have increasingly sought to tap into these rural communities, viewing them as breeding grounds for talented students who may not have had exposure to all their college options.

In recognition of such regional disparities, many of the nation’s top universities are boosting their efforts to reach out to high-performing rural students.

The problems of proportion

“There are wildly talented students all over the country, and it’s our responsibility to make Brown accessible,” says Dean of Admission Jim Miller ’73.

Many students do not have schools like Brown on their radar. Some have never heard of it, while others are intimidated by the hefty price tag. Even when admission officers travel the country, many states, especially in the Midwest, have such low population densities that it is impossible to hold information sessions reaching a broad swath of potential students.

High school students from certain rural areas are not applying to Brown and its peer institutions in great numbers, according to applicant demographic data.

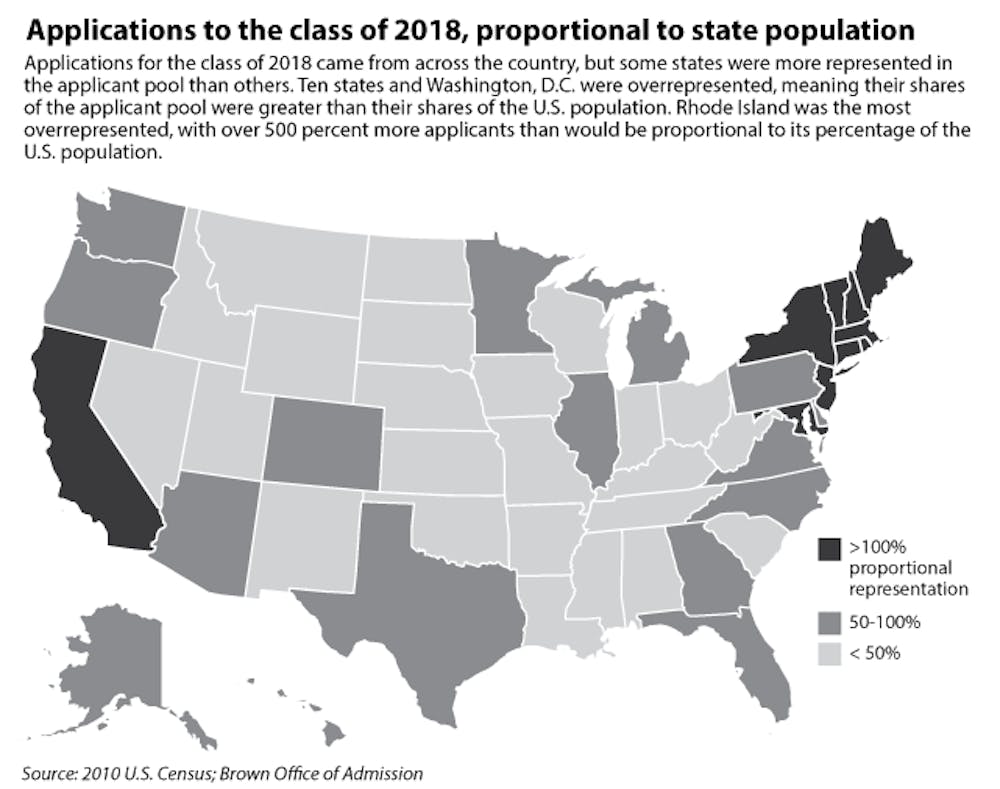

Even when accounting for population differences, many sparsely populated states account for a disproportionately small share of Brown’s applicant pool, according to data from the 2010 U.S. Census and applicant demographic data provided by the Office of Admission.

Though Florida and Texas account for a combined 4 percent of domestic applicants to the class of 2018, the states make up over 14 percent of the U.S. population. Low-population states in the Midwest and West like North Dakota and Wyoming have even lower rates of representation.

California, New York, Massachusetts and New Jersey were the top four states for applications in this year’s admission cycle and altogether represent nearly 50 percent of the domestic applicant pool.

Each of the New England states, as well as New Jersey, New York, Maryland, California and Washington, D.C., were overrepresented, holding significantly larger portions of the domestic applicant pool than their shares of the U.S. population.

Entering small-town America

Reaching students from rural and low-income backgrounds presents unique challenges, so many universities employ specialized methods to connect with these students.

The University buys high-scoring high school students’ contact information from the College Board in order to send them information about Brown. Such efforts publicize the University’s brand and financial aid options, Miller says.

Moving forward, the Admission Office is working to “use other electronic means … to reach as many people as we can,” he adds.

Admission officers also travel to rural regions, often participating in joint trips with peer institutions. The University has collaborated with two separate groups of peer institutions on nationwide travel, conducting one set of trips with the Massachusetts Institute of Technology and Yale and another with Cornell, the University of Chicago, Rice University and Columbia.

On such trips, targeted areas often include “a number of schools that have high populations of low-income students” as part of a goal of “reaching students we think might not normally talk about a place like Brown,” Miller adds.

The University also aims to publicize its need-blind admission policy better in order to attract low-income candidates, Miller says.

Brown isn’t the only school taking action. At a White House summit last month, over 100 higher education institutions announced wide-ranging commitments to opening the doors for a broader range of applicants, The Herald reported at the time.

Many of the initiatives announced at the summit involve boosting outreach efforts to students from rural and low-income backgrounds. Joint information sessions and travel trips as well as direct mailing, emailing and developing stronger social media presences are popular tools for universities.

But some peer institutions are stepping up efforts in more prominent ways than Brown. At the White House summit, Yale announced a new joint recruitment trip with Harvard, Princeton and the University of Virginia in the fall, according to information released from the White House. The trip will target underrepresented areas like South Texas, Arkansas and West Virginia with a message focused on accessibility.

“Everybody is very concerned about access and affordability,” says Lucie Lapovsky, principal for Lapovsky Consulting and an expert in higher education finance and governance.

‘Don’t apply to Brown’

Despite recruitment efforts to connect with students from all geographic backgrounds, obstacles ingrained in rural communities’ academic culture can be difficult to surmount.

For many Brown students, high school was a place for padding a resume — competing in a number of extracurricular activities and earning top SAT scores. Before high school even began, many knew they wanted to gain admission to an elite private university.

But many students from rural backgrounds grew up in more relaxed atmospheres with “different expectations for what people will do with their lives,” says Emma Funk ’16, of Fairbanks, Alaska.

The Admission Office takes environmental differences into consideration when making admission decisions, Miller says.

“We’re very conscious of what opportunities are available” to some rural applicants, he says.

Facing a dearth of rigorous academic opportunities, students who find their way to Brown from certain rural areas are often self-driven.

Audrey Fierberg ’15.5 knew she wanted to leave her 4,000-person town of Leland, Mich. In search of better opportunities than her hometown could offer, she chose to enter Bard College at Simon’s Rock, an early college in Massachusetts, after her sophomore year of high school. She graduated from Simon’s Rock last spring and came to the University this semester.

“I just couldn’t live where I lived anymore and get the education I needed,” she says.

Funk says her high school peers considered her “an anomaly” for her academic drive and desire to leave Alaska to attend a private institution. Fairbanks wasn’t a popular destination for college recruiters, Funk said, so she conducted college research on her own and with her family’s help.

Without access to admission officers, students like Funk must rely on themselves, families or high school counselors to learn about college opportunities.

Frequently, though, college counseling in rural areas falls flat.

Many high school counselors do not encourage students to pursue a full range of options, Lapovsky says, adding that students from these areas are frequently pushed toward public schools without learning about private institutions with generous financial aid policies. Counselors may not be prepared to help students with applying to more competitive schools.

“Guidance counselors have to encourage them to think of (elite schools) as realistic possibilities,” Lapovsky says.

Attending a university like Brown is “not in people’s consciousness where I’m from,” Lutken says. The counselors at his high school in Mississippi steered students toward state schools closer to home.

“Even my guidance counselors were like, ‘Don’t apply to Brown — that’s stupid,’” recalls Wesley Sanders ’15, who hails from Shepherdstown, W.Va. The teachers at his high school had never heard of Brown, and few classmates applied to comparable institutions.

‘East Coast culture shock’

But geographic background and the level of academic rigor might not be the only criteria that separate rural students from their peers.

“I think people aren’t always really conscious of their wealth at Brown,” says Margaret Dushko ’15, who is from a “tiny” village in upstate New York.

“I go to school with people who are a lot richer than I am,” Lutken says. His Mississippi county has massive income disparities and many people living in abject poverty. Lutken’s upbringing gave him a more frugal view of spending than many of his friends from the Northeast, he says.

Funk describes coming to Brown as “East Coast culture shock.” College Hill has more “conspicuous consumption” and “a different sense of how status works,” she says.

“It’s been a combination of privilege and random blessings that I’m here,” Fierberg says. Most students in her community come from low-income families, and some are children of migrant farm workers. Her hometown school system is underfunded, so college counseling often fails to prepare students to apply to competitive colleges.

“It’s heartbreaking, because there are so many people who do have talent who could succeed,” she adds.

For the students who leave their rural hometowns, the move to a larger city continues to be an adjustment.

Dushko’s hometown, Sherburne, is a village of about 1,400 in upstate New York. The girl who grew up among cornfields is baffled by comments about the slow nightlife in Providence.

Fierberg was also forced to adjust to urban college life. “It’s dead silent where I live, except for coyotes,” she says.

But leaving behind high schools with limited educational opportunities and entering a strong academic environment made the transition worthwhile, students say.

“I very much wanted to be somewhere radically different,” Funk says.

Sanders recalls his first impression of Brown during ADOCH — “fairytale-esque.”

Arriving on campus, he was excited to encounter students who were equally driven and passionate. “You come from a place where you’re a big fish in a small pond and suddenly you’re with all these other fast-swimming fish.”

ADVERTISEMENT