Neuroscience concentrator Pu-Ning Chiang ’16 is one of the 182 international students in her class year. Hailing from Taiwan, Chiang will rely on the Department of Homeland Security’s Optional Practical Training program to continue living in the United States legally following her graduation in the spring.

But the program has expired, and the federal government has until May 10 to make necessary changes. In the meantime, the fate of a number of international students, including some from Brown, is uncertain.

As an extension of the student visa, the OPT program gives international students and recent college graduates the opportunity to work in the United States for a year after graduation. In 2008, an extension was created that allows graduates studying science, technology, engineering and math to work for an additional 17 months, for a total of 29.

But in 2014, a labor union called the Washington Alliance of Technological Workers sued the DHS on the basis that international students were taking away jobs in STEM fields from American graduates. Now, the White House’s Office of Management and Budget must approve the program, or the 17-month extension will be eliminated.

In an email to The Herald, Elke Breker, director of Brown’s office of international student and scholar services, stated that the decision regarding the new proposal for the OPT program is expected to be released by March 10. This 60-day cushion should ensure that the verdict is made on time.

Breker declined to comment on how Brown students might be affected by a ruling in the future.

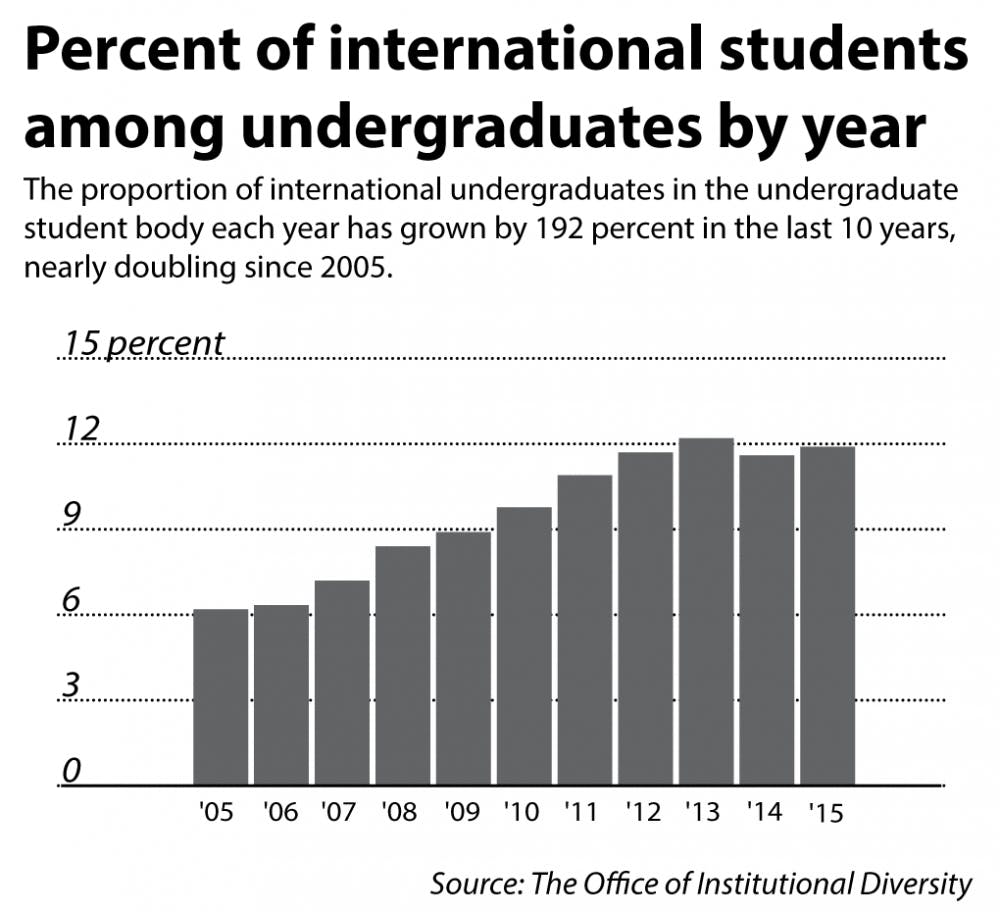

Thirty-seven percent of graduate school students at Brown are internationals, according to the graduate school’s website. Of undergraduates, 12.1 percent are international, according to statistics from the 2014-15 school year.

Tom Doeppner, vice chair of the computer science department, expressed his concern about the potential impact the elimination of the extension could have on international students concentrating in STEM disciplines. “OPT, as it is right now, is just 12 months. … If the extension goes away, it is going to make it pretty tough for our students to get their green card,” Doeppner said. “It’s going to have a negative effect on their education.”

According to Doeppner, there is a significant number of international STEM students and recent graduates from Brown working through this program in his department.

As a student thinking about pursuing OPT for neuroscience following graduation, Chiang said that the extra time granted by the extension would better her experience. With only a year to work, rather than 29 months, she would have less time to apply for a worker visa.

Entering the lottery for a visa is risky — especially with a time constraint — as only 65,000 are available each year, according to the U.S. Citizenship and Immigration Services website. Without acquiring a worker visa following the initial 12 months granted by OPT, Chiang could have to leave the country, a situation she has seen a friend forced into before.

“We all want to stay here,” Chiang said. “America is a good place. I like it here.”

But should the plan currently under review be approved, Chiang will be granted more time in the United States than she would have had under the original extension. Among other revisions, the new proposal by the DHS would bump the 17-month extension to 24 additional months on top of the original 12 for a total of 36.

The suggested update to the law would also implement protection for American workers in response to the criticism by WashTech, according to media site Marketplace. Under the revised OPT program, preventative measures would be put in place to stop employers from hiring foreign workers in the place of Americans.

But, according to the National Science Foundation, hiring international workers does not necessarily indicate that American workers will be displaced from jobs.

In the computer science department at Brown, there does not seem to be a problem, Doeppner said.

“As far as our students and graduates are concerned, they’re all getting plenty of job offers, and there’s no notion that international students are taking job offers that should otherwise be going to American students,” he said.

Concerns about the shortage of STEM labor demand aside, the OPT program’s extension is widely well received for expanding international students’ workplace opportunities and advancing U.S. technology as a whole.

“For the country in general, there is a shortage of qualified people for high-tech jobs. And if we do anything that makes it more difficult for highly qualified people graduating from top universities to continue on in high-tech positions, it’s going to be bad for the country’s tech industries, which is going to make us less competitive with the rest of the world,” Doeppner said.

Others feel the OPT program serves a purpose other than bolstering America’s STEM research.

John Miano, the lawyer representing WashTech workers in the lawsuit against the DHS and a fellow at the Center for Immigration Studies, said the OPT program is modifying student visas in order to compensate for a problem within the system to attain a worker visa. Rather than amend the OPT program to gain more high quality workers, the DHS should attempt to control the quality of workers applying for worker visas, as the system is currently overflowing with relatively low-skilled workers, Miano said.