Few words carry such an immediately visceral cue for solemnity, mourning and remembrance as “Holocaust.” The knowledge of the horrors that took place at the hands of the Nazis during the Second World War is pervasive today; elementary school children read works such as “Night” or “The Boy in the Striped Pyjamas.” The idea that somebody could deny the atrocities of the Holocaust is absurd and almost unsettling, but that ideology persists even today. The most poignant aspect of “Denial” is perhaps not the plot or the performances or the writing, but the dates that flash up at the bottom of the screen: 1995, 1998, 2000. The conflict does not take place in the confusion of 1945, but in the same year that “Harry Potter and the Goblet of Fire” was published.

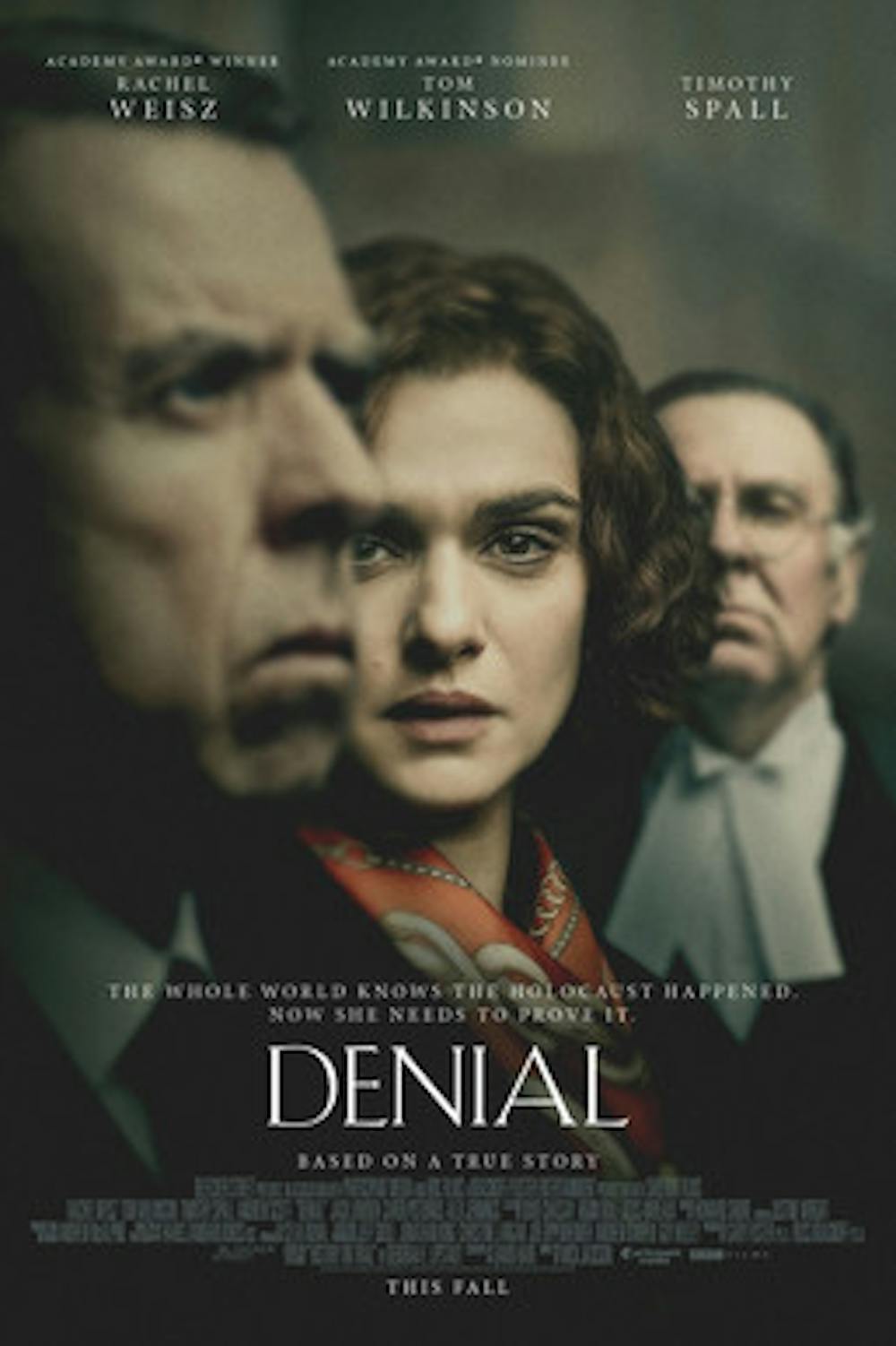

“Denial” is the cinematic adaptation of “History on Trial: My Day in Court with a Holocaust Denier,” an autobiographical work by Deborah Lipstadt. The film details the court case Irving v. Penguin Books, in which David Irving, a historian played by Timothy Spall, claims that Lipstadt, a Jewish professor at DeKalb University played by Rachel Weisz, libeled him as a Holocaust denier in a work of hers. Irving asserts that Lipstadt’s claims are unfounded because his revocation of the Holocaust was the natural conclusion he came to after examining historical evidence. Lipstadt retorts that Irving deliberately manipulated information to foster his claims.

The movie opens with Lipstadt giving a talk to a group of university students about the Holocaust, where she emphasizes that while she is happy to debate the how and why of the Holocaust, she refuses to argue with anyone who flat-out denies it. Lo and behold, Irving is in the back row, listening indignantly before interrupting to berate Lipstadt and offer $1,000 to anyone who can produce photographic evidence of the genocide.

The rest of the film details Lipstadt and her defense team’s preparation and execution of the libel suit. In the United Kingdom, where the case was filed, the burden of proof rests on the defendant, so the pressure is on. Lipstadt’s defense team consists of Anthony Julius, a wry and charming intellectual known for serving as Princess Diana’s divorce lawyer played by Andrew Scott; Richard Rampton, a boozing, cigarette-smoking barrister with unconventional methods played by Tom Wilkinson; 23-year-old paralegal Laura, played by Caren Pistorius; and a handful of vaguely British, vaguely lawyerly supporting players. Irving chooses to press charges in trial by judge, not jury.

Suffice to say that the most interesting thing about the movie is the story it was based on. One is left with the unshakable suspicion that director Mick Jackson and writer David Hare got together and asked each other, “How can we do everything within our power to get Rachel Weisz an Oscar?” The answer they came up with was to surround Weisz with milquetoast and lesser-known performers for her to act at. She delivers long-winded and derivative speeches in a “Queens” accent (which for Weisz is something between Janice from “Friends” and U.S. Sen. Bernie Sanders, I-VT) on the importance of having a voice, fighting for the truth and not backing down. This would not be so terrible if she had chemistry with literally any of her supporting cast members.

Hare’s screenplay throws subtlety to the wind. “We need to hear your voice!” a reporter in a press gaggle repeatedly cries out to Lipstadt immediately following a scene in which she was informed that neither she nor any Holocaust survivors would be testifying. The greatest lines go to Wilkinson, who gives the best performance in the film — most likely because he is the only performer who does not take himself very seriously.

Jackson’s direction recalls the gold-tinged, sweeping, big-budget films of the late 90s, most notably “Shakespeare in Love” and “Titanic.” The best moments come when Jackson allows the movie to breathe, as he does with naturalistic views of London or shaky, intimate shots of private conversations. For the most part, Denial employs grandiose cinematography to continually remind us that Lipstadt and her team are the heroes.

The majority of what is wrong with the film comes from its lack of a clear core identity. Is it a reflection on the intricacies and tragedies of the Holocaust, a condemnation of the English judicial system, a meditation on the power of teamwork, a feminist look at two male-dominant fields or a lesson in pride and humility? In better hands it may have achieved all of the above, but here it falls flat.

The film’s greatest accomplishment is its refusal to allow Irving any slack. Though it is revealed that neglect and abuse during his childhood in the 1940s caused him to find comfort in the demagoguery of Adolf Hitler, “Denial” paints him as pathetic rather than deserving of sympathy. The conclusion of the movie details the important precedent set by the case’s decision in favor of Lipstadt, which leads to a warm and fuzzy celebration followed by one final sappy edict from the perpetually hammy Weisz.

“Denial” takes an interesting and historically crucial tale and turns it into a movie you’d fall asleep to on an airplane. The film is best described as Oscar-bait-bait, something that knows it probably won’t win all that many awards but needs you to know it could have if it had wanted to.

Correction: A previous version of this article stated that the character Richard Evans was played by John Sessions. In fact, the character's name is Richard Rampton and played by Tom Wilkinson. The Herald regrets the error.