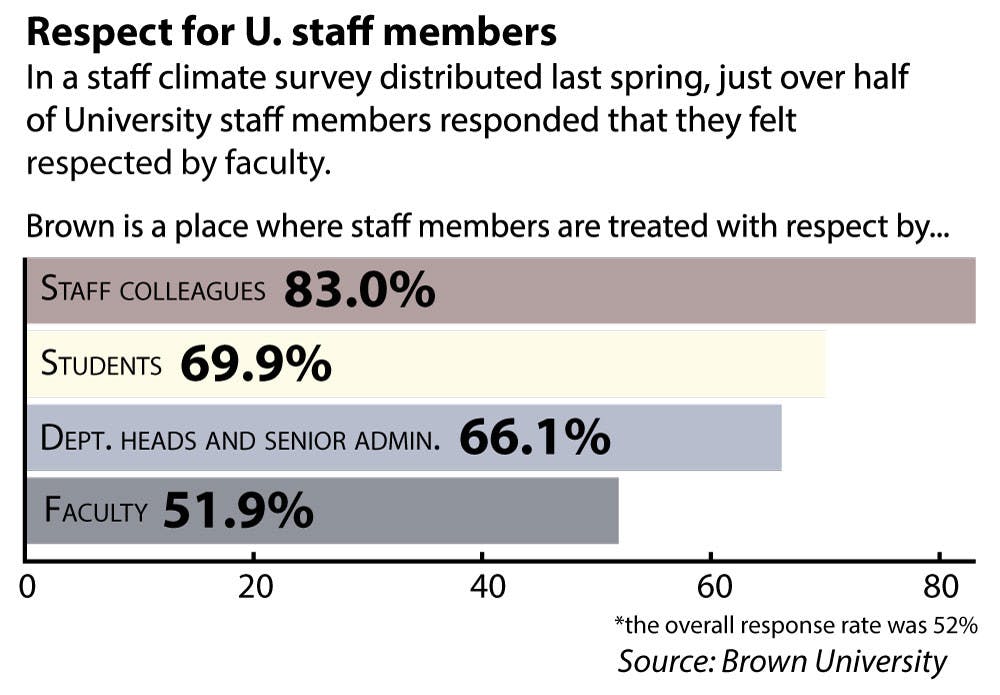

The results of the spring 2016 staff climate survey, which indicated that only 52 percent of respondents felt they were treated with respect by faculty, have prompted responses and re-evaluation of faculty-staff relations from the University and its individual academic departments.

The senior managers of departments or units with more than five staff members generally received their specific survey results for their department, said Karen Davis, vice president of human resources. The University had never previously conducted a staff climate survey, she added.

Planning for the survey began in January 2016 as a way of measuring the progress of efforts outlined in the Diversity and Inclusion Action Plan, Davis said.

The survey aims to provide a baseline for planning departmental and University-wide efforts, said Jennifer Casasanto, associate dean of the Department of Engineering.

“Overall, the results University-wide were actually pretty positive,” Davis said. The 14-question survey had a response rate of 52 percent, and results were broken down by gender, race and ethnicity. Given the response rate, “to the best of our knowledge, the vast majority of staff don’t necessarily feel” disrespected by faculty, she added. But the results still highlight a larger issue: the tensions that underlie relationships between faculty and staff.

Reviewing the results

A faculty-staff “cultural divide” and the failure to include staff in discussions of big picture decisions could account for the 48 percent of respondents who did not feel respected by faculty, said Kevin McLaughlin, dean of the faculty.

Different faculty and staff priorities might contribute to staff “feeling a little bit like they’re subordinate to faculty,” McLaughlin said. While staff are focused on the world of the University, faculty are “in a place — intellectually and professionally — that really isn’t at all limited to the campus,” he added.

Faculty can be impatient with staff when they are under pressure, in a hurry or expect perfect service immediately, McLaughlin said.

Kenneth Silva, physics laboratory manager, said that if he were a new staff member unfamiliar with his position, his interactions with faculty might not feel positive. But, he said, “I’ve been working here for 15 years … so generally my labs are fairly smooth.”

In administrative offices and academic departments, “staff people are usually operating at one step in a chain of a longer process and they … don’t have a sense of what the big project is,” McLaughlin said, adding that this could make staff members “feel understandably like they’re not important.”

“Faculty and students are really the reason we’re all here,” Davis said. “I think staff sometimes feel they get lost in that equation.”

Throughout the University, many staff members “do feel pigeonholed” and deprived of opportunities for “advancement” and “cross-training,” said Purvang Patel, member of the Staff Advisory Council and a biology department manager. When staff “approach their managers … they’re often reprimanded,” he added.

Staff members could also have a general perception of the faculty as “uncaring” as a whole, but that sentiment might not extend to specific faculty members in their respective departments, McLaughlin said.

“If there’s one faculty member in a department who treats people with less respect, people will tend to feel that very intensely, and it will carry over to their feelings about the rest of the faculty,” said Willis Peter Bilderback, brain and neural systems department manager.

McLaughlin said that “the level of staff feeling appreciated in the humanities departments was lower than that in other parts of the University.” This discrepancy could be due to the greater amount of collaboration and contact between staff and faculty in STEM departments, who work together on research and in labs, he added. Humanities staff “may feel that there’s a lot of faculty in their department who don’t even know they exist,” McLaughlin said.

Planning a response

The University and its departments are aiming to better understand the results of the survey and take steps to address the reasons for the lack of respect some staff perceive.

When the staff climate survey was announced, the engineering department was already planning its own staff survey, Casasanto said. “We asked to collaborate and we found a way to add our own engineering questions to the survey because we wanted to dig deeper into inclusion topics,” she added.

Eighty percent of respondents from the engineering department indicated that they felt respected by faculty, Casasanto said.

Engineering has also since launched four staff recognition awards, Casasanto said. Recipients are nominated by other staff members, faculty and students and receive a small gift donated by the upper management of the department, she added.

A sense of disrespect towards staff is specific to some departments, Patel said, adding that the survey results do not reflect his department. Biology tries “to do things that bring staff and faculty together” to promote personal connections and collective decision-making, he said.

McLaughlin also suggested inviting staff to meetings hosted by the dean of the faculty so they can get a larger picture of the University’s priorities.

Department chairs should make an effort “to team-build and have events that incorporate both faculty and staff,” Bilderback said. Educating faculty in the proper ways to interact with staff is also vital, he added.

Through faculty and staff retreats and team-building exercises, the engineering department encourages faculty and staff members to see themselves as a united group working to overcome the same challenges, Casasanto said.

The engineering department hopes to continue to improve its work environment and use the survey data to spark conversations with staff about how such improvements can be made, Casasanto added. With feedback from staff members, the department has already begun to run custom diversity and inclusion trainings that focus on concerns specific to the department, she said.

A turnover in department leadership may be necessary to implement changes that would increase a sense of respect among staff, Patel said. Managers who have been at Brown for many years may be insulated and lack input from resources outside the University, he added.

The University recently replaced its Management Development program with the new Leadership Certification program, which allows staff to choose their own courses of study as they train for leadership roles, Davis said. The program “teaches you about how to coach employees, how to make them strive for excellence … and how to deal with different employees,” Patel said. “I would highly recommend it.”

The program is currently available to all “newly hired, newly promoted staff” and can serve 175 to 200 staff members at any one time, she added. A participant must take 12 courses to graduate from the program. The first graduation ceremony took place in fall 2016, Davis said.

The University’s performance review program has also been overhauled based on community feedback, Davis said. The revised process, which will be rolled out this spring, should “feel less bureaucratic … and do a better job of supporting a good conversation between an employee and their supervisor,” she added.

At a University and departmental level, the results of the staff climate survey are being used to evaluate and make alterations to the various departmental Diversity and Inclusion Action Plans, Davis said. Plans are also underway for more qualitative studies to further explore the survey results, she said, adding that the survey will likely be repeated every two or three years.

“It may be that we’ll find an answer (to the root cause of perceived disrespect) that cuts across all employee groups,” Davis said. “But it may be that it does really depend on what your role is at the University, where you work, (and) what your relationship is to faculty.”