Student activists gathered to discuss prison abolition at a teach-in on Wednesday night, bringing forward their concerns with the prison-industrial complex and proposing ways to move toward its eventual disintegration.

“Prison Abolition 101” was organized by RailRoad, a student collective that works within the University and with local organizations to radically change the justice and prison systems to move toward “a world where the Prison Industrial Complex has been destroyed,” according to their Facebook page.

RailRoad members began by introducing the concept of prison abolition before diving into a group discussion about why prison reform is insufficient. While the group’s official stance does not explicitly include prison abolition, a number of RailRoad members are prison abolitionists.

“The end goal is to not have prisons as any form of incarceration,” said RailRoad member Grace Austin ’23, while presenting at the event. “Punishment at any stage doesn’t guarantee any kind of growth.”

Aida Sherif ’22, who also presented at the event, said that while prison abolition may seem radical, the roots of the criminal justice system make the process of locking up felons irredeemable.

“Prisons were founded in the ideas of punishing the poor, punishing people of color,” Sherif said. “I don’t see it as an institution that can ever fully break away from those foundations.”

The teach-in did not outline explicit plans or a timeline to achieve prison abolition. All RailRoad members interviewed emphasized that prison abolition was a long-term goal that could be facilitated in a number of ways, including creating alternative institutions for justice. Sherif added that society should not assume prisons are necessary institutions to achieve justice.

“Our society is constructed in a way that would have us believe prisons are absolutely necessary,” Sherif said while presenting at the event. “People perceive it as crazy, unreasonable, dangerous, too radical. Abolition is not anarchy.”

The presenters encouraged resisting the construction of new prisons, strengthening communities and establishing forms of alternative justice as first steps toward abolition.

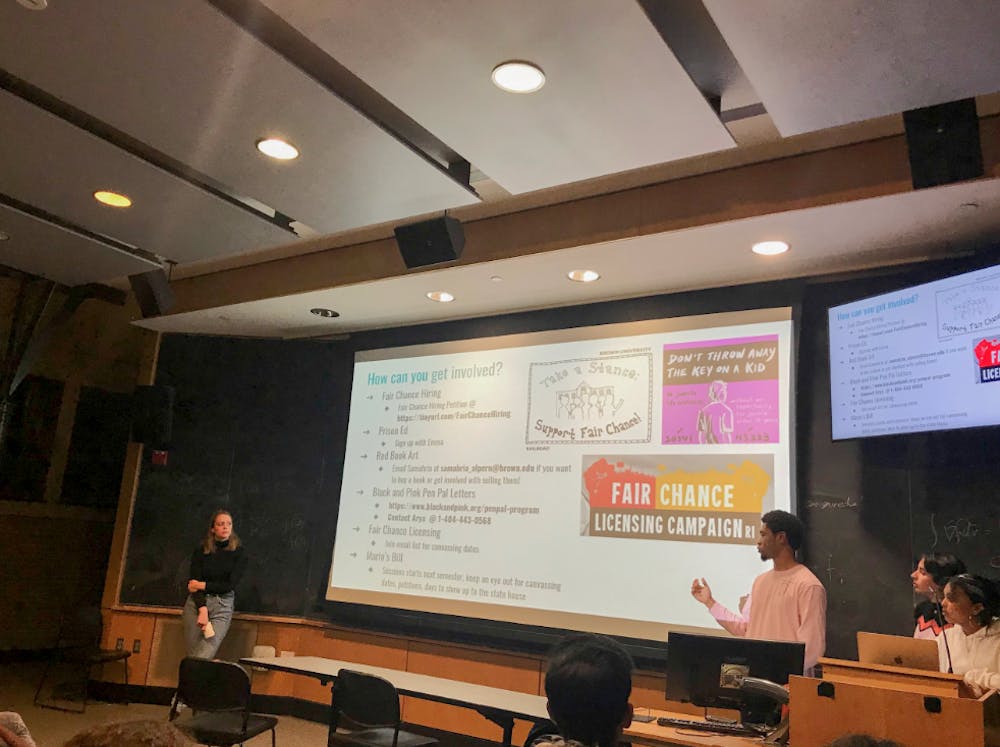

RailRoad is currently leading a campaign to encourage the University to adopt “fair chance” hiring practices, such as including conviction history in its non-discrimination statement and committing to hire a certain number of people who have been incarcerated. They also advocated encouraging New York City Councilman Stephen Levin ’03 to vote against a plan to fund the construction of new jails in New York. Education about prison abolition could create more interest in these ongoing campaigns, said Leah Shorb ’20, a RailRoad group member.

“If people aren’t totally on board with the issue of mass incarceration and prison abolition in general, then they may not necessarily be as convinced about fair chance hiring,” Shorb said. She views campaigns like fair chance hiring as a mechanism to move the needle toward prison abolition as well. “Anything that is interrupting the cycle of incarceration is abolitionist to me as long as it’s not further entrenching the system of incarceration,” she added.

RailRoad members also discussed other steps toward prison abolition, ranging from the decisions of individual judges to national legislation. At the state level, a judge from Ohio gave one criminal the option of wearing a chicken suit in public in lieu of a jail sentence. At the national level, New Zealand enacted stricter regulations dictating when police can arrest juveniles and implemented a restorative justice approach instead of formal court proceedings.

The event’s audience was about evenly split between RailRoad members and members of the general public, Austin said.

Marko Milic ’23, a non-member who attended the event, said previous readings and interactions with the issue of criminal justice system reform led him to the event. “I got introduced to it watching things like “13th” on Netflix,” he said, referencing the eponymous documentary focused on the racial inequity present in the American criminal justice system.

Wednesday’s teach-in may not be the last. Austin noted the potential for an in-depth follow-up “prison abolition 201” session that allows for more community discussion.

“We want to generate more conversation about all the different ways you can go about transitioning to a world without prisons,” she said. “The information we presented, you could fully unpack that for hours.”

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.