When students receive their financial aid awards, the packages reflect a web of forms and information: the Free Application for Federal Student Aid, College Scholarship Service profiles and other interactions with the Office of Financial Aid. But sometimes, financial circumstances change — an unexpected medical cost or a parent’s recent unemployment might make an award insufficient for a family’s need.

The primary safety net for students unable to meet expected tuition contributions is the appeals process: a mechanism within the Office of Financial Aid that allows students to present new information that may justify an increased award.

Three students who went through the appeals process told The Herald that, once they were informed about the proper procedure, a combination of meetings, storytelling and a tall stack of documents led to meaningful change in their aid packages.

The majority of financial aid appeals come from accepted first-year students deciding if they can afford to attend the University, according to Dean of Financial Aid James Tilton. In their appeals, they supplement the information they may have already given the University on a CSS Profile or Free Application for Federal Student Aid.

“Often there’s not enough space for (first-year students) to tell us everything,” Tilton said. “When we send out the first award, I almost expect them to come back and say, ‘Did you get everything?’”

The appeals, Tilton added, come from a common piece of advice: the idea that students should “never take the first offer.”

Tilton estimated that 45 percent of accepted first-years receiving financial aid ask for a “second look.”

Oscar Barbaza ’23 fell into Tilton’s estimated 45 percent: he filed an appeal almost immediately after the University admitted him. Without an increase in aid, Barbaza said he likely would have attended the University of North Carolina, Chapel Hill, in his hometown.

Students also often leverage financial aid packages from other institutions. In response, the University will examine whether they differ significantly from Brown’s offer or include merit-based aid, Tilton said.

“We look at (appeals) individually” in order to determine if the office might have missed a significant detail in a student’s financial application, Tilton said, mentioning a case where a student forgot to disclose that they had a sibling paying for college at an Ivy League school.

When students who have already enrolled appeal their financial aid, Tilton said, it usually has to do with a major financial shift in their life. “For an appeal, something drastic has happened. There’s going to be a difficult time meeting the expected contribution,” he said. Other discussions about minor aid changes can happen without the appeals process.

Emily Redolfi Tezzat ’21 has appealed her financial aid twice since enrolling at the University: once at the end of her freshman year when her mother changed jobs and again before studying abroad her junior year.

Before her first appeal, when Redolfi Tezzat realized that her aid package would not be sufficient given her mother’s recent change in employment, stress immediately set in. She thought through a number of options, including seeking help from extended family, applying for scholarships or taking on an additional on-campus job. Ultimately, she decided to appeal her package.

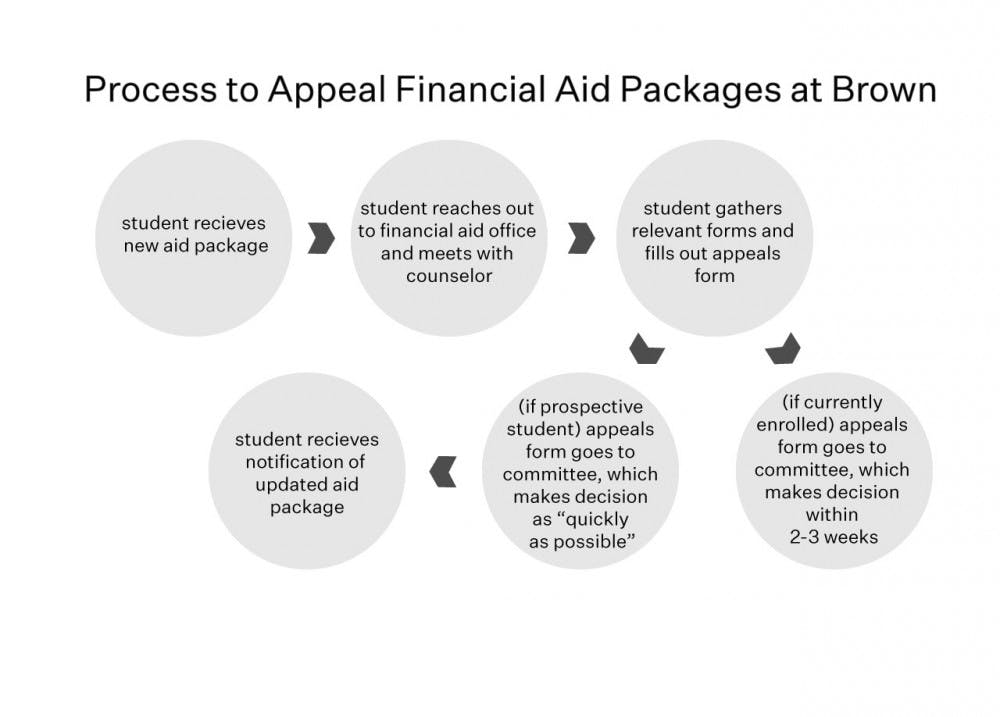

No matter if they’re an admitted student or already enrolled, Tilton said, students should reach out to the Office of Financial Aid before filing an appeal.

“Let us know that something’s come up,” Tilton said. Students are assigned a financial aid counselor who walks them through whether or not they should appeal and offers them relevant information once they decide to start the process.

“We’d be able to say, ‘This is what we’d expect would be helpful,’” he said. “It’s helpful for you and your family to think about what you say to us when you’re appealing your situation.”

Barbaza said that making his circumstances clear and having his family’s financial information prepared — tax returns, other financial statements and predicted family income — were pivotal factors when he spoke with an aid counselor.

After a counselor meeting, students fill out an appeal form to request a “review of (their) financial aid award.”

Listing a number of potential reasons for an appeal, including a “significant loss of income” due to a change in employment, a death in the family and high medical, educational or familial expenses, the form says the University won’t consider an appeal on the basis of personal expenses or high consumer debt, expenses that have yet to occur or siblings in graduate school.

The form also requires a detailed explanation and documentation of new costs. In some situations, appeals also require parents’ tax returns and a W-2 form.

For Micah Bruning ’22, the appeals process began when his mother told him about a costly surgery she would need to treat cancer. The process became stressful when Bruning explained to his parents the myriad of forms and documents needed for a successful appeal.

“It’s difficult to try and explain what you need,” Bruning said. “They don’t always understand how the University’s bureaucratic process works (or) why the University needs certain stuff.”

Once filed, appeals go to a committee for review, Tilton said. The speed of the process varies based on the time of year. It might take 48 hours to a week mid-year, but it could take far longer in the summer, after financial aid awards are released in June.

Given that students may see aid as a deciding factor in choosing between schools, the office tries to process the appeals of incoming first-years as “quickly as possible,” Tilton said.

Barbaza said he received a new package with considerable time to spare. “That was the difference between me staying in my hometown and me going here,” he said.

The difference in packages, he said, was notable but not major: the first offer relied on his submitted FAFSA and CSS profile, and the second offer more closely reflected additional documents and explanations.

In Redolfi Tezzat’s case, making a compelling case to an aid counselor before submitting an appeal was the most pivotal part of the process.

“You have to prepare to be politely aggressive,” she said. “Being able to argue for the fact that you genuinely do not have that money and point to specific parts of your tax returns or changes in your income — they can’t really argue against facts.”

Students don’t appeal for a specific amount of money, Tilton said, but he emphasized that most commonly, an appeal leads to some change in an aid package, large or small.

Bruning, Redolfi Tezzat and Barbaza all received increases in aid from the appeals process, but the transparency and accessibility of the process could still be improved, they said.

When Bruning’s appeal went through, he received an additional $3,500, but his mother’s surgery cost roughly $5,000 after insurance.

“They gave me a reduction in my total costs, but they didn’t really justify why,” he said, unsure if the gap between the additional aid and the cost of his mom’s surgery had to do with changes to his family’s income the year he appealed.

And while the appeals process made a difference for Redolfi Tezzat — within three weeks of submitting her appeal for her sophomore year, the aid office updated her award — she said the process remains largely inaccessible.

“I have helped so many people in my class, some of my upperclassmen friends, sophomores with the appeals process,” she said. “A lot of people don’t know you can appeal in the first place.”

An additional challenge posed is the unexpected nature and timing of changes in circumstances, which are frequently out of students’ control, Redolfi Tezzat said.

“These things happen when students are in the middle of midterms. We have our personal lives with our clubs and our family drama,” Redolfi Tezzat said. “It can be very nerve-wracking, asking for money — it takes a lot of swallowing your pride, to do what is institutionalized begging.”

She added that she “showed up at (the Financial Aid Office), and as we were talking, the stress collapsed in on me. I started crying.”

Redolfi Tezzat said she found it helpful to work through her case with a friend, a CAPS counselor and a dean before bringing it to the Office of Financial Aid.

Barbaza, though, said that in the end, he thinks the Office of Financial Aid is “doing what they should be doing.”

“They were very helpful,” he said. “A couple of my friends appealed and got a portion of what they asked for. They’re giving everybody a fair shot at it.”

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.