Scientists, researchers and space enthusiasts convened at Brown’s annual Space Horizons conference from Feb. 8-12, where they attempted to answer some of the most pressing questions in space exploration and research: How can we ecologically sustain human activity on the moon? How do you maintain a cooperative international society beyond Earth? And how do you convince the public that a space exploration program is even necessary?

Speakers from across the globe with expertise ranging from ecology to public policy to theology gathered virtually at the event, titled “Making Space Sustainable,” said Adjunct Associate Professor of Engineering and co-organizer of the event Rick Fleeter ’76 PhD ’81.

Each day of the event focused on a different theme with regard to sustainability in space, from “sustaining public involvement” to “sustainable space ecosystems,” said Anthony Capobianco ’21, the lead student organizer for the event.

Fleeter founded the Space Horizons conference after growing frustrated that the space industry stopped “pushing the envelope” on what was possible. “There were lots of good ideas out there and either the government wasn’t funding it or private companies weren’t investing in it,” Fleeter said. Space Horizons took on the mission of finding interesting endeavors that nobody else was pursuing and asking, “Why aren’t we doing it?”

The conference previously involved round-table discussions with experts, Fleeter said. The organizers tried to maintain the interactive nature of the conference when transitioning to a virtual format due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

Noting people’s shortened attention spans over Zoom, the organizers spread the event over five days from the typical two and shortened the length of the conference each day to about an hour and a half, Fleeter added. The organizers further subdivided every day into three parts, with two main speakers bookending a “halftime show” in which a student or a guest lecturer presented their work on space research for five minutes to “keep the screen moving” and retain attention.

Hosting the event virtually also enabled the organizers to more easily attract experts to participate without having to coordinate travel and lodging accommodations, Capobianco said.

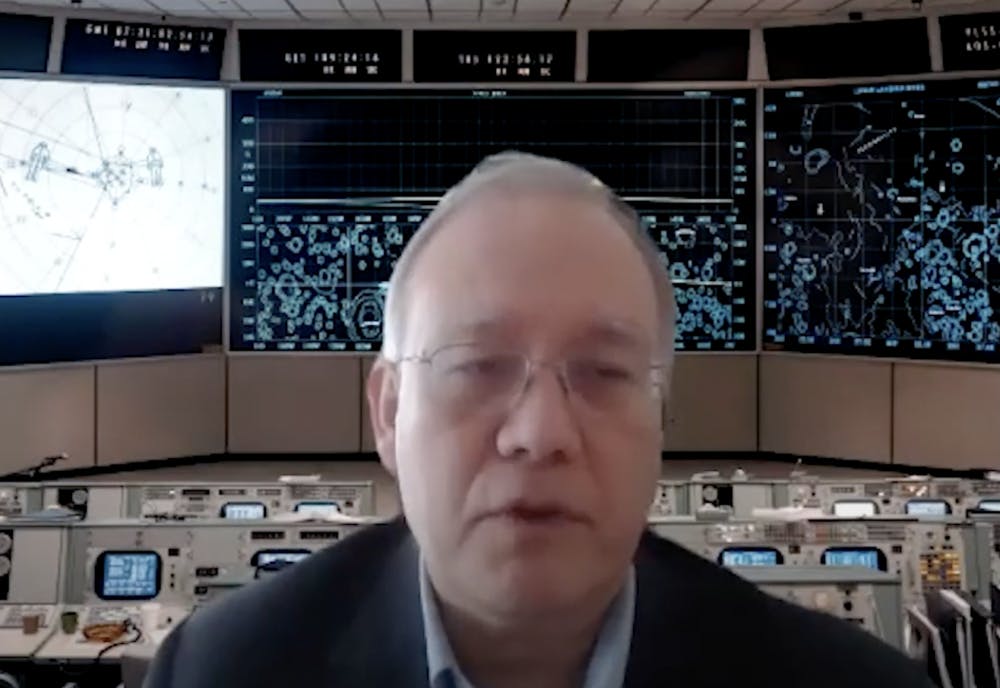

One of the event’s featured speakers was Scott Pace, former executive secretary of the National Space Council and current professor and director of the Space Policy Institute at George Washington University, who discussed his experience and accomplishments working closely with former Vice President Mike Pence. He promoted U.S. interests in space, including establishing the U.S. Space Force and drafting the Artemis Accords.

Space exploration and research can be a useful tool to build lasting international relationships and vice-versa, according to Pace. Since space is a much more globalized and democratized environment now than it was during the Cold War, when the United States was trying to prove what it could do by itself, cooperation across all sectors is more important than ever. “International involvement (and) engagement is really what's going to make the program ... viable for the longer term,” Pace said.

Space cooperation can allow the United States to promote its values abroad, Pace added. “Space is an area that's not subject to claims of national sovereignty,” Pace said. But “as you get other sovereign states voluntarily to agree with you, to cooperate with you and align with you,” you can influence other states and promote U.S. values, such as the rule of law, democratic institutions, mixed market economies and human rights, Pace said.

John Adams, deputy director of Biosphere 2, and Kai Staats, director of A Space Analog for the Moon and Mars, presented together at the event. Biosphere 2 is a 3.14 acre, hermetically sealed earth science research facility run by the University of Arizona that tests the viability of living in closed ecological systems, and SAM is the smaller version of Biosphere 2 designed to sustain life outside of Earth.

A self-sustaining ecosystem on the moon or Mars is critical if humans want to have a more permanent presence outside of Earth, Staats said. Without a way to grow food, frequent resupply missions would be the only way to sustain human life, Staats said, but this method is unsustainable over the long term.

Biosphere 2 is investigating the viability of growing fungi or introducing insect larvae into a closed environment to break down inedible food waste for consumption, Staats said.

But sustaining life for even the smallest animals requires a large amount of space. “There's just no way that we can ever recreate Earth and pack it up and take it somewhere else,” Adams said.

Dealing with challenges within a closed system requires different solutions than on Earth, Adams said. For example, as the plants mature within a greenhouse, they develop their own microbiome, which could clog nearby air filters or damage electronics. To prevent unwanted growth around these areas, “you can't just throw bleach or chemicals on it because in a (completely) closed environment that bleach doesn't go away,” Adams said. “Any harsh chemicals that you put in your environment, you are breathing in.”

Charity Weeden, vice president of global space policy at Astroscale U.S., led a discussion on the challenges and economic opportunities brought on by space debris in the lower Earth orbit. “Over the last six decades, both government and industry … have been polluting Earth's orbit,” Weeden said. This pollution comes from remnants of rockets and space satellites that have collided. But there was “never any worry about the ... long-term impact of leaving upper stage rocket bodies in orbit.”

There are currently over 100 million pieces of debris in the lower Earth orbit that could catastrophically collide with satellites, Weeden said. Many investors of satellite systems place an economic value on the calculated cleanliness of a potential satellite orbit, she added.

Astroscale works to clean up large pieces of debris, many of which are reusable and have high economic value.

Weeden is also developing international policy to maintain a debris-free lower Earth orbit as the commercial space industry grows. She hopes that governments step in to form their own programs to remove small pieces of debris that have little economic value yet could still damage satellites.

Joseph Lillard ’24, who is interested in engineering and entrepreneurship and attended the conference, noted that Space Horizons “brings the correct balance of optimism and analytics into an environment where it gets people fired up to want to continue the passion of space” while also being realistic about the expectations of space research.

Space Horizons has “been a really good opportunity for me to develop a bunch of different life skills but also be able to engage with people who are just as passionate about space as I am,” Capobianco said, reflecting on his final year organizing the conference. “Being able to spend a few days really just immersed in space is just a great thing.”

ADVERTISEMENT