With the semester just beginning and over 100 positive COVID-19 test results on campus, University health experts agree rapid antigen tests are a pivotal tool for students to keep both themselves and others safe.

But unlike PCR testing, which offers little room for improvisation, at-home test-takers have the chance to take liberties with their test kits: swabbing their throats instead of their nostrils, or even sharing swabs to make the most of limited test supplies.

Though the University requires students to test twice a week, students can take the at-home tests at their convenience, The Herald previously reported.

The Herald spoke to University professors and public health experts about the best times to take a rapid test and the best practices while testing.

When to test

Executive Vice President for Planning and Policy Russell Carey ’91 MA’06 said that beyond ensuring that 24 hours pass between tests, students should not specifically plan on taking their test around classes or other activities

“It’s important to do two tests in each seven-day period,” he said. “I wouldn’t tie it to classes or anything like that.”

The testing requirement “makes sense” given the University’s policies that mostly assume students will not spend time indoors unmasked, said Megan Ranney, founding director of the Brown-Lifespan Center for Digital Health and professor of emergency medicine.

But if students socialize indoors without masks, those events become “far safer” if everyone involved takes a rapid test immediately beforehand, Ranney added.

She also advised students not to “test the minute that you find out you’ve been exposed.” Instead, testing every three to four days “picks up the majority of infections,” she told The Herald.

William Goedel PhD’20, assistant professor of epidemiology at the School of Public Health, said that students might choose to test “right before a group activity around others who don’t have masks on” — and again 36 hours after the event, as the test instructions suggest.

A negative test is not a “free pass to do everything normally,” Goedel added. “Negative means ‘good to go right now, but proceed with caution.’”

Students must report in the MyBrown portal that they have taken their two tests each week and notify the University only if they test positive. If students have not done so “by roughly the fourth day (in the week), students will start getting reminders and requests to report in the MyBrown portal that they’ve taken their test,” Carey said.

Antigen tests are “protective and a good way of assessing risk, but they’re not foolproof,” said Abdullah Shihipar MPH’20, a research associate at the School of Public Health. Shihipar has written about the pandemic and public health for The New York Times, The Washington Post and Business Insider.

In a recent article for Teen Vogue, he called for a number of increased public health measures to combat the Omicron variant, including “stimulus checks and … hazard pay while nonessential businesses are closed for a few weeks until cases go down to a more manageable level.”

In an “ideal world,” Shihipar said he would take a rapid test twice a day if he were a student and try to wait out the last weeks of the Omicron surge by skipping unmasked in-person events. But given the current limitations, he added that he would prioritize testing before and after “small, in-person gatherings” and other environments with more interpersonal interaction.

Shihipar said that he personally would not go to an indoor unmasked event at all, at least until March, to “get the (Omicron) wave under control.”

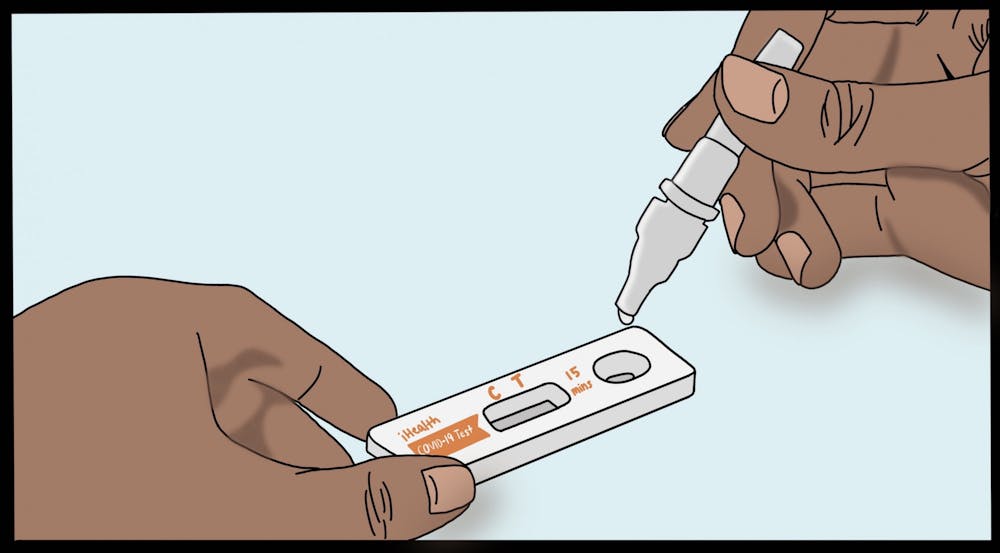

How to take and read a rapid test

The University is currently using test brands such as iHealth and Quidel QuickVue, which can be found in local pharmacies or CVS. These tests are specifically authorized for individual at-home use and can be taken without supervision, according to Carey.

While the tests all have slight differences in their instructions, they each require the user to swab their nose, mix with a pre-supplied reagent and wait a certain amount of time — usually between 10 to 15 minutes — for results to appear.

“There’s always the possibility for something to go wrong or for some element not to be in the test kit when (students) open the box,” Carey said. But he added that so far, the University has not had any concerns with the transition to self-administered testing.

One key difference between rapid tests and PCR tests, according to Ranney, is that the swab does not need to go as deep into the nasal cavity as a swab for a PCR test.

Reading the test is simple, Goedel said. “Antigen tests look a lot like pregnancy tests — one line if it’s negative, two lines if it’s positive.”

Goedel added that students should not concern themselves with how bright or strong the second line indicating a positive result is. While a particularly bright line may signify a higher concentration of proteins — and therefore higher infectiousness — students should read the tests one of two ways, Ranney said: positive or negative.

“I wouldn’t want people sitting there, trying to judge, ‘I’m only a faint line, so I don’t need to isolate,’” Ranney said. “If there’s two lines, then you’re infectious.”

If students feel sick, Ranney emphasized that they should not go “out and about,” even after testing negative. Rapid tests, she noted, can show up negative before the tester has a high enough concentration of the virus to test positive.

“That’s not the time to go to the dining hall unmasked,” she said. “If you have symptoms, don’t hang out with other people.”

If students stay symptomatic for a few days after testing negative, she said, they should test again.

More recently, questions have arisen regarding whether throat swabs might pick up the virus earlier than nasal swabs, according to pre-prints of research papers and anecdotal reports.

“I certainly am aware that there’s opinions in different directions” about nasal swab versus throat swab, Carey said. “The bottom line is people should follow the directions.” The tests the University distributes, he emphasized, are nasal swab tests.

Ranney and Goedel both agreed. The tests, Ranney said, are FDA approved for nasal swabs — and the “chemistry of the back of your throat is different than the chemistry in your nose.” Studies show nasal swabs still pick up COVID-19 well, she added.

PCR vs. Antigen tests

Compared to the previous PCR testing model, “on a per-test basis, (antigen tests) are certainly less expensive,” Carey said. But the financial impact did not drive the decision, he noted.

“PCR tests would be very likely to pick up students who had (COVID-19) three weeks ago and probably didn’t even know they had it,” Carey said. “Forcing those students to isolate … is just not good for anybody included, especially the students, so the antigen tests are a much better solution.”

Goedel said that he was initially “surprised” by the change in testing “because it felt very much like a quick shift.” But he added that for a highly vaccinated and boosted population such as the Brown community, switching to antigen rapid testing has “been part of the conversation in the public health world for the last couple months.”

A PCR test — which stands for polymerase chain reaction — is a diagnostic test that determines if you have COVID-19 by analyzing a sample, such as a nasal swab, to see if it contains genetic material from the virus. “PCRs can take a very small amount of genetic material from a sample … and amplify and replicate that to see if there’s viral genetic material in the sample provided,” Goedel explained.

Since PCR tests are “very sensitive” they do not always show “if the virus is capable of infecting someone (or) if it’s capable of causing symptoms,” Goedel said. With a PCR test “it’s hard to tell who’s super infectious and who just has a little bit (of virus) in their nose … without symptoms, because their vaccines are still working strongly,” he added.

Antigen tests, on the other hand, pick up people “likely to spread (the virus) to other people,” because “you have to have a lot of virus in your nose for a rapid (antigen) test to pick it up,” Goedel said.

While “PCR testing is (better) for campus surveillance, rapid testing is more convenient for before you meet up with someone or for your own daily surveillance,” Shihipar said. “It’s great if you can use them both because they fill different niches.”

Beyond the test

The University’s mitigation strategies, Ranney emphasized, are layered. Vaccinations and boosters are the first step. But high-quality masks such as KN95s — which the University currently provides — and air filtration also play a major role in preventing Omicron from “moving through like wildfire,” Ranney said.

“Our prevention and mitigation strategies are multi-layered for a reason,” Goedel said. “Testing helps us pick up people quickly and get them out of contact with lots of people. Masks help us from keeping viral particles out of the air, as does our air ventilation.”

Goedel added that if students recognize any symptoms resembling a cold, they should stay home — even with a negative test result.

“It could be COVID, could be the flu,” Goedel said. “Regardless of what a rapid test says, you should be skipping whatever event you’re going to.”

If students are sick, they should also engage with Brown Health Services to get tested for other common college illnesses, such as the flu or mono, Ranney said.

There is also another way to significantly limit the relative risk of any event, with or without tests, Shihipar said: high-quality masks such as KN95s or KF94s.

“If people are masking, or masking most of the time, … it’s not like there’s zero risk, but you are reducing the risk,” he said.

A study from early 2021 — predating the Omicron variant — showed that an N95 can protect its wearer from someone who is infectious and unmasked for 2.5 hours. If two individuals are wearing N95s, the study found that it would take 25 hours of interaction to spread COVID.

Outside of purely social events, college life also entails countless small moments in shared spaces — work in a dorm lounge, a walk to the bathroom or a shower in a communal bathroom.

Whether or not students should mask in those gray areas comes down to a number of factors, Ranney said. They should consider their own risk of severe illness — but also the risks that other members of their community face.

“There’s no perfect answer,” she said. “For the vast majority of students who are vaccinated and boosted, the chance they get severely ill is tremendously low.”

Those students, she said, might feel confident taking off their mask to shower in a shared bathroom. But the recommendations might be different for students who are immunosuppressed or face other health risks, she added.

“I’m pretty confident that our students, like our faculty and staff,” Ranney said, “can hold this (pandemic) at bay.”

Gabriella was a Science & Research editor at The Herald.

Will Kubzansky was the 133rd editor-in-chief and president of the Brown Daily Herald. Previously, he served as a University News editor overseeing the admission & financial aid and staff & student labor beats. In his free time, he plays the guitar and soccer — both poorly.