Ninety-five years after Virginia Woolf published her thoughts on the lack of representation of relationships between women in literature, these concerns still ring true to an alarming degree across modern media.

“All these relationships between women, I thought, rapidly recalling the splendid gallery of fictitious women, are too simple,” Woolf wrote in “A Room of One’s Own.” “Almost without exception they are shown in their relation to men.”

Most Hollywood movies still fail the now well-known Bechdel Test — to pass, a film must have at least two women in it who talk to each other about something other than a man. The test itself is by no means an adequate measure of how media should portray women. If anything, it only makes the much-too-frequent failure of movies to meet the criteria more disquieting.

Not only are fictional women portrayed disproportionately in regards to men, they are very often pitted against each other — whether it’s in a love triangle or as a “pick me girl.” For every Batman and Robin or Sherlock Holmes and Dr. Watson, there’s a Serena and Blair fighting over Nate or a Maddie and Cassie fighting over Nate — again.

While the same disparity is present in literature — from the patriarchal society of Jane Austen’s England to Toni Morrison’s repressive midwestern towns — many women in these novels have found a safe haven from patriarchal society in friendships with other women.

“What is friendship between women when unmediated by men?” Morrison asks in her foreword to “Sula.” Although this question has been answered to varying degrees over the years, the resulting conversations have not been nearly frequent or loud enough to break through the “catty woman” or “mean girl” tropes that still dominate modern fiction.

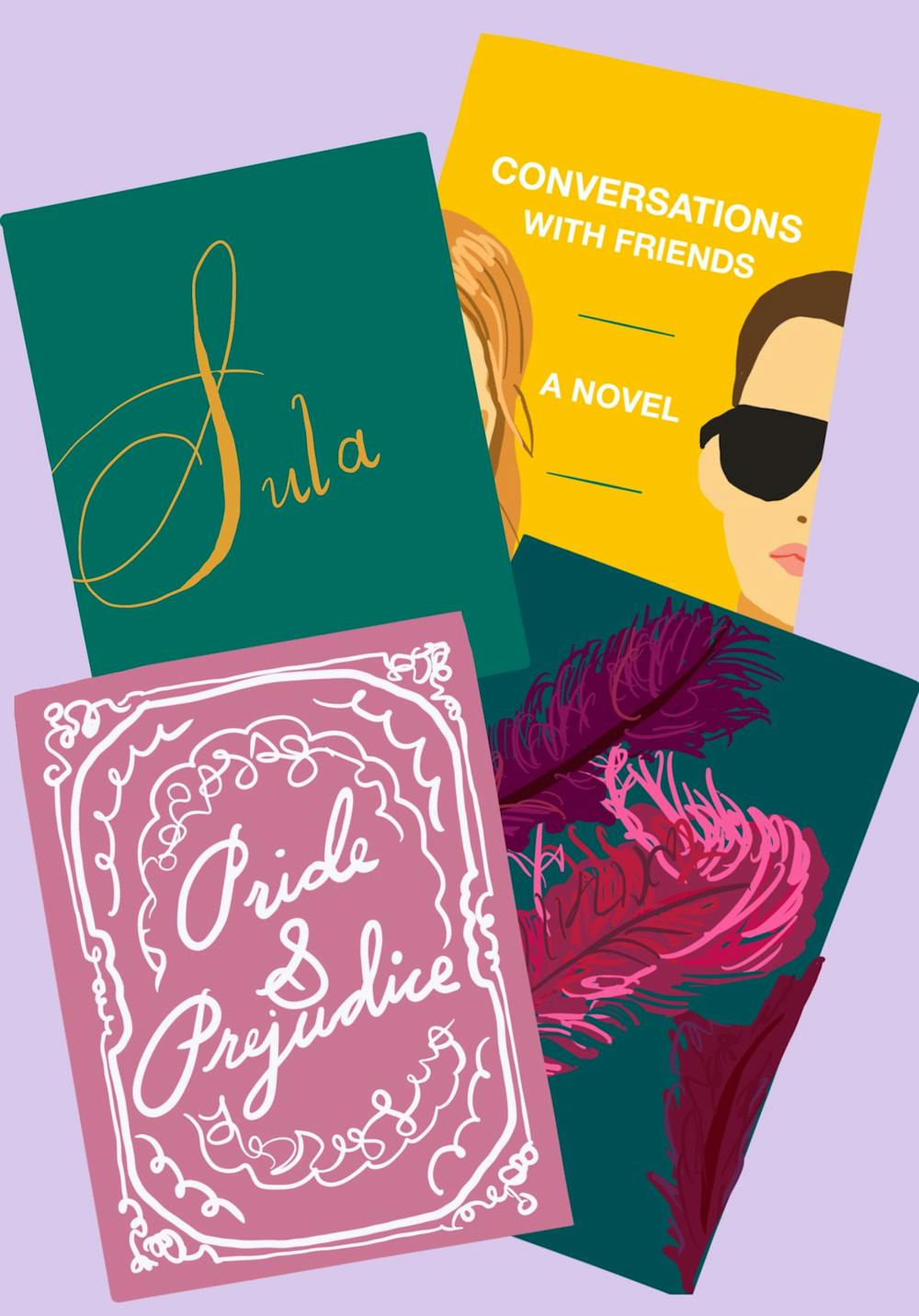

In an attempt to counter this narrative, here are five novels that feature female friendships that are complicated and far from perfect, but also nuanced, powerful and crucially “unmediated by men.”

“Sense and Sensibility” by Jane Austen

“Sense and Sensibility” follows sisters Elinor and Marianne Dashwood within their upper-crust English society. Like all of Austen’s novels, “Sense and Sensibility” is — at least in terms of plot — about marriage. But there is a reason Austen has persisted in popularity through the centuries: she holds a mirror up to society, simultaneously exposing its ugliness and its warmth. And “Sense and Sensibility” is full of both.

At the heart of the novel is the relationship between Elinor and Marianne — their individual arcs eventually lead to the reconciliation of drastically different worldviews. Elinor and Marianne embody “Sense” and “Sensibility” respectively, and their relationship is as complex as the tensions between the two faculties. In fact, Marianne’s ultimate epiphany at the novel’s climax is essentially a realization of her respect for her sister.

While it is not uncommon for Austen to portray an irreplaceable sisterly bond — like that of Jane and Elizabeth in “Pride and Prejudice” — “Sense and Sensibility” is arguably her most striking investigation of how far sisterhood can be tested and her most profound celebration of its boundlessness.

“Sula” by Toni Morrison

“Sula” is Toni Morrison’s poignant attempt at answering her own question: What does a female friendship look like when it is unmediated by men? The friendship between Sula and Nel reaches a level of intensity that becomes transcendent — it gives them an escape from the intersectional systems of oppression that dominate their world.

“In the safe harbor of each other’s company they could afford to abandon the ways of other people and concentrate on their own perceptions of things,” wrote Morrison in “Sula.” When Sula and Nel are together, they are no longer subjected to the hierarchical gaze of society, which relegates Black women to the bottom rungs.

“Because each had discovered years before that they were neither white nor male, and that all freedom and triumph was forbidden to them,” Morrison wrote, “they had to set about creating something else to be.”

Their friendship also acts as an essential part of their personal identities — Morrison’s women are not defined in their relation to men, but in terms of a relationship independent from men, a bond built and fostered by women alone.

This in itself was revolutionary, but what makes Sula such a radical testament to the power of female friendship is Nel’s realization at the end of the novel that she missed Sula far more than her husband, following years of separation from her sister. With four reflective words, Morrison captures the depth of their friendship, which supersedes the bond of marriage: “We was girls together.”

“My Year of Rest and Relaxation” by Ottessa Moshfegh

“My Year of Rest and Relaxation” does not portray a wholesome or healthy friendship. The relationship between the unnamed narrator and her best and only friend Reva is dysfunctional, to say the least — but this novel thrives on dysfunction.

The narrator decides to put herself into a pill-induced year-long hibernation for “self-preservation.” Her repulsion for Reva — for her bulimia, neediness and tendency to quote self-help books — becomes clear from the very beginning of the novel. In fact, her merciless descriptions of Reva throughout the novel are matched only by the mercilessness with which Moshfegh criticizes the narrator herself.

Through the characters’ selfishness, there is a sense of loyalty and attachment that persists between the narrator and Reva. And through layers of intoxication and isolation, they are the only real connection in each other’s lives. But none of this is redemptive, and their relationship borders on sadomasochism.

Still, it is not the influence of a man that makes their relationship toxic. Their dynamic is terrible because they are terrible people — and as simple as that sounds, it is a shockingly rare phenomenon. The one-dimensionality of female characters is equally prominent in negative portrayals of women as it is in positive ones — it’s almost always “a woman scorned” or some rivalry over men. So Moshfegh’s depiction of female friends is absurdly refreshing even as it is fittingly twisted.

“Beautiful World, Where Are You” by Sally Rooney

Rooney’s first novel, “Conversations with Friends,” portrays an intense, homoerotic and fluid relationship between two women, Frances and Bobbi, through college. Alice and Eileen, her protagonists in “Beautiful World, Where Are You,” are on the cusp of their 30s and have already moved past this overwhelmingly intense phase. For a significant part of the novel, they are in different cities, communicating only through long emails about everything from the man Alice meets on a dating app to the rise and fall of civilizations.

Like all of Rooney’s protagonists, they are hyper-intellectual: Rooney turns emails into an art form with the same adeptness as she did normal conversations in her first two novels. Her characters meticulously break down the nuances of the large, sometimes abstract notions in these emails, yet their attempts to communicate and empathize with each other on a personal level often ends in failure or frustration. But their tenderness and deep respect for each other never wavers. Their lives may diverge but their emails remain a shared space over the years, even throughout the pandemic lockdown toward the novel’s end.

Friendships between adult women are particularly sparse in fiction, and Rooney captures acutely Alice and Eileen’s careful preservation of intimacy through the course of their lives.

“City of Girls” by Elizabeth Gilbert

“City of Girls” is significantly breezier than the others on this list, but it is a vibrant celebration of female sexuality and friendship. Set in a pre-World War II New York City, the book follows Vivian Morris as she leaves behind suffocating upper-class morals to live with her Aunt Peg, the black sheep of her family.

What follows is a glamorous romp through the 1940s — one that is full of alcohol and sex but also an all-consuming friendship with the “goddess-like” showgirl Celia Ray, which ends in a calamity that is also the novel’s turning point. The second half follows Vivian’s far more meaningful growth over the next few decades, as she finds steady friendships with women that she eventually grows old with.

Gilbert’s women are vibrant, while her men fade into the background. The novel’s structure is a case in point. Written as a letter from Vivian to the mysterious character Angela, it is an inherently female space.

Despite being drastically different from each other and often less than perfect, all five of these novels depict powerful, multifaceted friendships between women. It is easy to buy into stereotypical narratives of drama, betrayal and cattiness in female relationships. But in actuality, women have been building connections that transcend patriarchal limitations throughout history, in literature and in life.