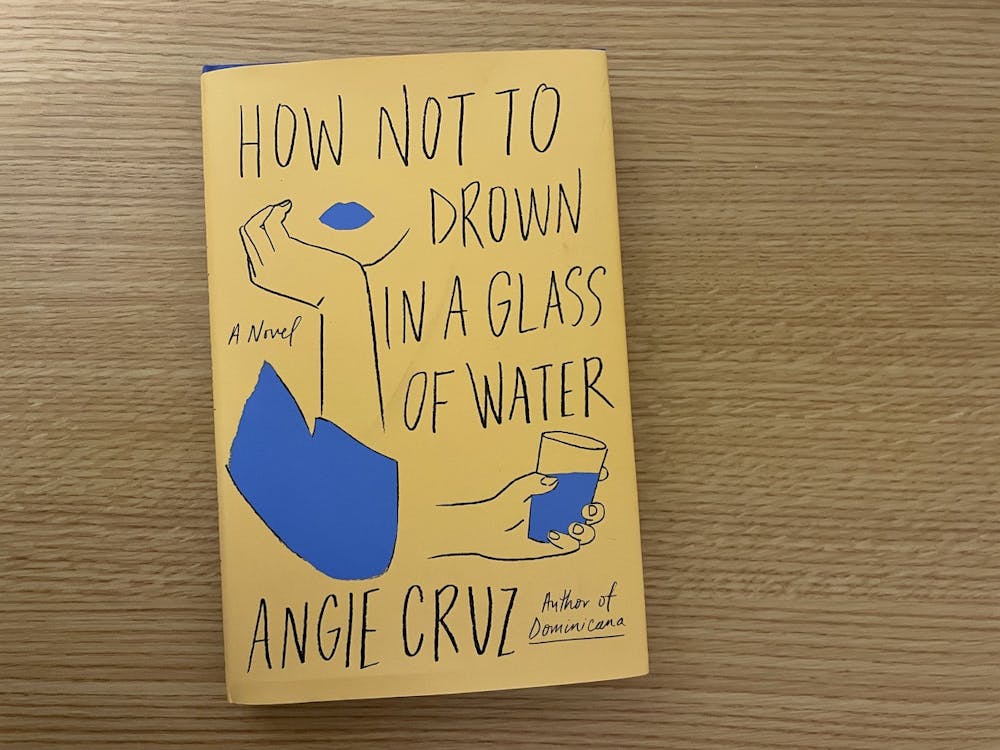

In Angie Cruz’s latest novel “How Not to Drown In a Glass of Water,” protagonist Cara Romero explains that, in Spanish, “desahogar” means “to drown, to cry until you don’t need to cry anymore.”

The story follows Cara’s attempt to “undrown” over the course of twelve sessions with her career counselor. As her appointments begin to resemble therapy sessions, we learn more about Cara’s past in the Dominican Republic and the debt and loss she struggles with in New York against the backdrop of gentrification and the Great Recession.

It doesn’t take much for Cara to overshare. In her own words, when she’s asked about mangoes, she talks about yuca. “Sometimes we need help to not drown in a glass of water,” she said.

But even as this process of sharing becomes therapeutic for her, she rejects the idea of therapy: “That’s what therapists make you do. They make you spit on your mother,” she alleges. “Everything is the mother’s fault.”

Although she resists at first, it is difficult to miss the biting irony when she finally talks about her own mother’s abusiveness and the generational trauma that has evidently shaped her life despite her insistence otherwise.

Through her warm, humorous and undeniably distorted accounts, we learn more and more about Cara’s multifaceted relationships and the community she builds in her apartment building in Washington Heights — including her fractured relationship with her son, her turbulent relationship with her sister Ángela, and her loving relationship with her neighbor, Lulú.

But as she reveals more about her life, we come to realize that Cara is deeply flawed in seemingly unforgivable ways.

Cara asserts early on that her son “abandoned” her, and it is only towards the end of the novel that she reveals why he left — a fight which escalates from Cara forbidding him from leaving the house in tights.

Cara fails to understand her son, which is undeniably wrong on her part. Yet this does not undermine her deep-rooted love for him, which shines through across the novel.

She does unforgivable things, but she is not unforgivable — Cara is the product of an extremely complicated emotional and cultural past, and, even as she fails to understand, she is trying to repent.

This is one of the strongest points of the novel: Cara’s resistance to moral categorization complicates the very idea of black-and-white categories that readers might default to. Through her protagonist, Cruz achieves the necessary function of good literature: to make readers uncomfortable in a generative way, and to “expand consciousness,” as Ottessa Moshfegh said.

Cruz further dissolves any sweeping moral judgements a western audience might be tempted to make by capturing acutely the nuances and tensions of cultural assimilation from the Dominican Republic to the U.S.

This is partially depicted through the characters’ frequent code-switching between English and Spanish, but also through how Cara’s understanding of family differs from the American perception — although she is flawed, her family ties run deep. Her confusion at the ease of family detachment in America is not surprising: “What is wrong with this country? So cold,” she says.

Coming from a collectivistic culture to one of the most individualistic countries in the world is a culture shock for Cara, although it might not be a glaringly obvious one. She lives in the same building as her sister’s family — in two different apartments, but always one house, as Cara says.

“But even when we fight, we eat dinner together, like a religion,” she says. “Food, I tell you, fixes things.” We see that food is Cara’s love language throughout the novel — another marker of her collectivistic roots —- and it fittingly ends with Cara bringing her counselor home-made Pastelitos to thank her.

Understanding this fundamental difference makes it far easier to understand Cara’s resistance and fear about her sister leaving her behind, and her total confusion at her son’s decision to leave. That is not to say that either Ángela or her son Fernando were wrong — it is just a demonstration of the characters’ resistance to clear moral judgements.

Cruz’s novel is as bold and inventive structurally as it is thematically. The unbroken second-person narrative serves to maintain a certain level of intimacy with Cara’s audience — the counselor she speaks to and readers of the novel alike. And as we are propelled forward through a series of Cara’s intensely personal monologues, we can’t help but feel a degree of warmth at her largely happy ending.

“Write this down,” she says, “Cara Romero is still here, entera.”