While the John Carter Brown and John Hay libraries have housed Native American and Indigenous materials within their collections in the past, there had never previously been a cohesive curation to them. That was until Kimberly Toney, the inaugural coordinating curator for Native American and Indigenous collections, was brought on board in July 2022 to help the libraries expand this field of knowledge on College Hill and beyond.

Currently, most of Toney’s work at the two libraries centers around contextualizing the materials already at the University rather than acquiring new ones.

“It's not necessarily about reconfiguring the collection or even adding to the collection,” Toney said. “I'm here to sort of help think through what exists here, how it's described here, how folks do or do not feel like they have equitable access to the materials here and how we think mindfully about stewarding them or taking care of them.”

The JCB’s Native American and Indigenous collections, which primarily focus on American materials up to the mid-19th century, were mostly written by non-Native voices — usually missionaries or architects of land deals, according to Toney.

These works largely “deal with histories of indigenous populations that suffered under the violence of settler colonialism,” Toney said.

Toney hopes the curated works will open up conversations about the relationship between Native American and Indigenous history and forces of settler colonialism — a relationship that brought about institutions such as Brown.

Because the JCB is open to the general public, the collections provide new opportunities for those outside the University community to critically engage with these materials.

“We want to think about how we take care of those things in a way that (gives access to) communities who are here today and are still connected to these materials,” Toney said.

Part of this community-engagement initiative comes in the form of the recently announced JCB Research Fellowship for Indigenous Communities, which “supports community-prioritized and community-based research that would benefit from research time in the JCB’s collections, that could be undertaken, for example, by Native or Indigenous scholars, Elders, Tribal librarians or archivists and knowledge keepers,” according to the library website.

The fellowship is not restricted to academics working in traditional institutions of higher education, but rather open to the general research community of Native and Indigenous scholarship.

Toney’s new curatorial role opens up opportunities to bring voices with personal attachments to the materials into the University.

“I've invited my own Nipmuc relatives and Narragansett relatives and Wampanoag folks to come and just sit and talk about things and think about things without any kind of need to generate paperwork,” Toney said. They “think about how these materials might be used by a community that's connected to them or not, (and) how we might think about them in the institution or talk about them and describe them.”

“The way people represent themselves, want to be represented, talk about themselves, want to share things or do share things, is, I think, directly related to or can be directly put into conversation with what that means for how we've talked about people or for people for a long time in these institutions,” she added.

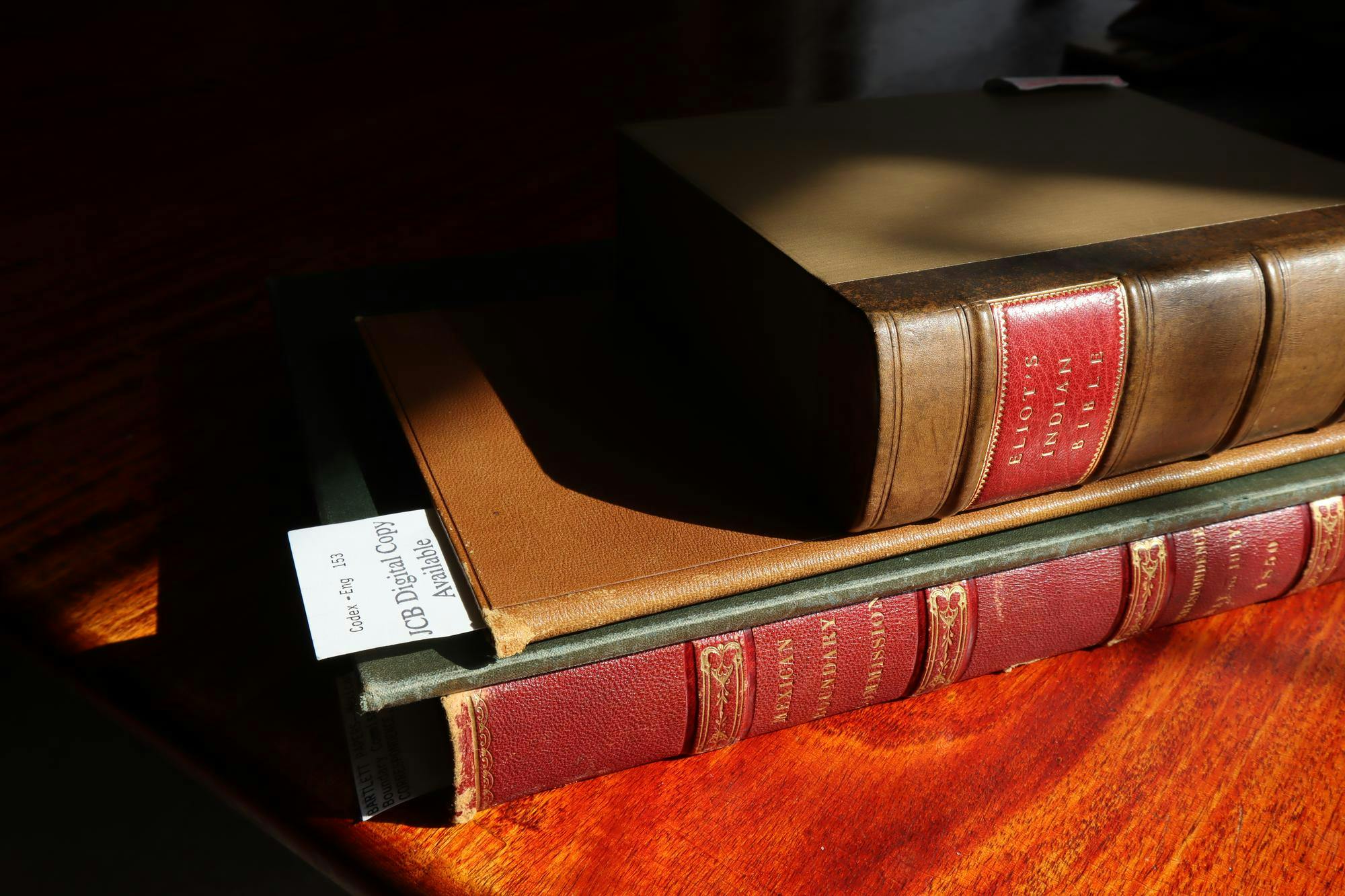

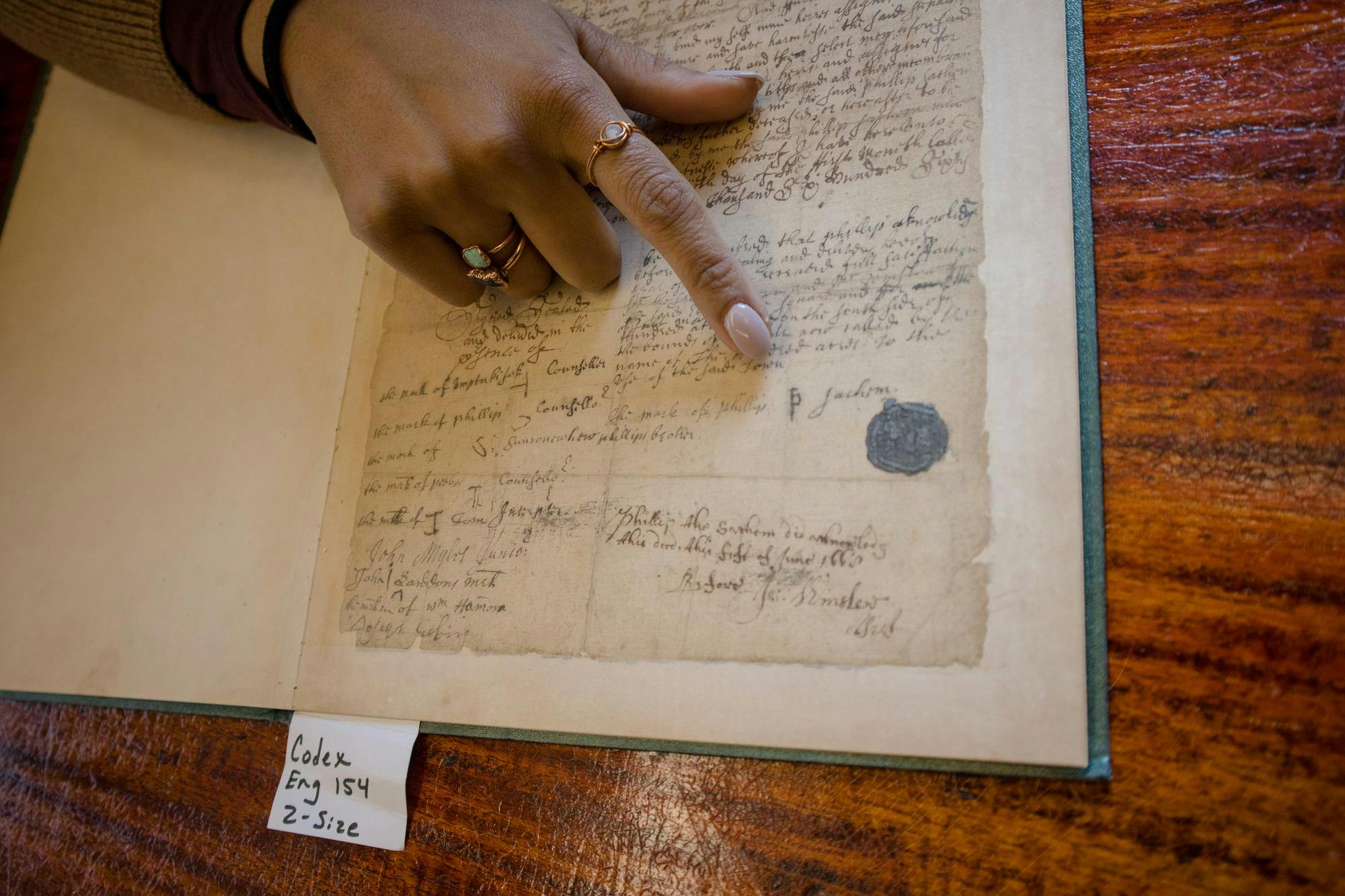

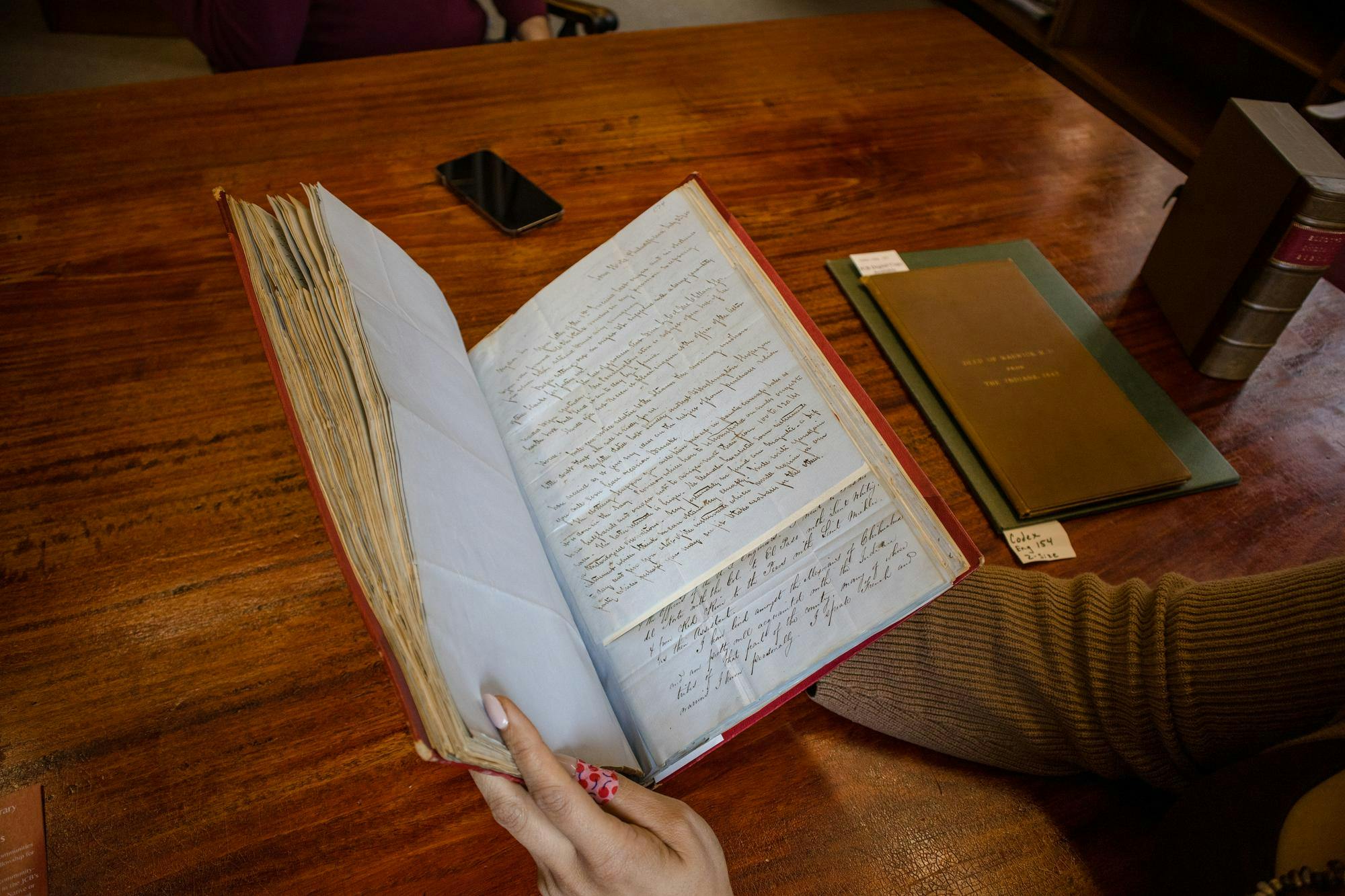

Toney showed The Herald some of the materials in the JCB’s collection — a bible, land deeds and documents from the U.S. Boundary Commission.

Known as “Eliot’s Indian Bible,” the bible was first published in British North America. While its intention was entirely for religious conversation at the time, it has since become a crucial text for preserving the language it was written in — a generic form of the Algonquian languages, according to Toney.

The existence of the text highlights a crucial question Toney says she continues to work through — how to actively understand the Native experience through the lens of colonial publications. Toney sees their abstract existence as immeasurably crucial, in spite of the means they were created for.

Toney said that once she learned about the book’s production by “real Native people” and its capturing of “the languages that they were speaking to each other,” she became more comfortable with its existence.

Toney added that while she is sad the Bible was written with the intent of furthering colonialism, she sees her community, the people that she connects with and the importance of learning language in the book.

“I'm glad that we have access to what lives in these pages,” she said.

Other materials in the collection include two land deeds, one of which was for the land that would eventually become Warwick. These documents show firsthand the methods colonizers took to seize land in the 17th century. They also show the cultural barriers that were exploited. For example, since the Native tribes in the area were not writing cultures, the members who signed these documents did so with pictographs instead of written words, Toney explained.

These documents remain pertinent today when considering the land we all walk on, Toney said, particularly at an Ivy League institution. “I often try to stay very grounded in place when I'm here, so that, for me, is definitely tied to land and how we think about land and how we relate to land, how we occupy land.”

The final shown material was a book from the collection of John Russell Bartlett, a former librarian at the JCB in the 19th Century as well as U.S. Boundary Commissioner. It is a collection of back-and-forth letters about the work of the Boundary Commission, including watercolor drawings. The work shows the attitudes of the U.S. government influenced by beliefs in manifest destiny and demonstrates the reach of JCB’s collection beyond the Northeast.

Outside of the JCB, collections are also housed in the John Hay Library. These materials are complementary to what is in the JCB and include work from contemporary Indigenous voices — including comics, zines, poetry and other modes of expression. The Hay also houses growing collections focused on language and food sovereignty.

Comparing more contemporary materials with what is in the JCB, Toney said: “Supporting the voices of contemporary Native folks can do a lot to help us think about how that is or is not happening in the earlier sources, and what that looks like.”

For Toney, both collections are “critical for us understanding each other, or sort of shaping a world — a way of viewing the world but also a way of being in the world and relating to each other.”

Finn Kirkpatrick was the senior editor of multimedia of the Brown Daily Herald's 134th editorial board. He is a junior from Los Angeles, California studying Comparative Literature and East Asian Studies. He was previously an arts and culture editor and has a passion for Tetris and Mario Kart.