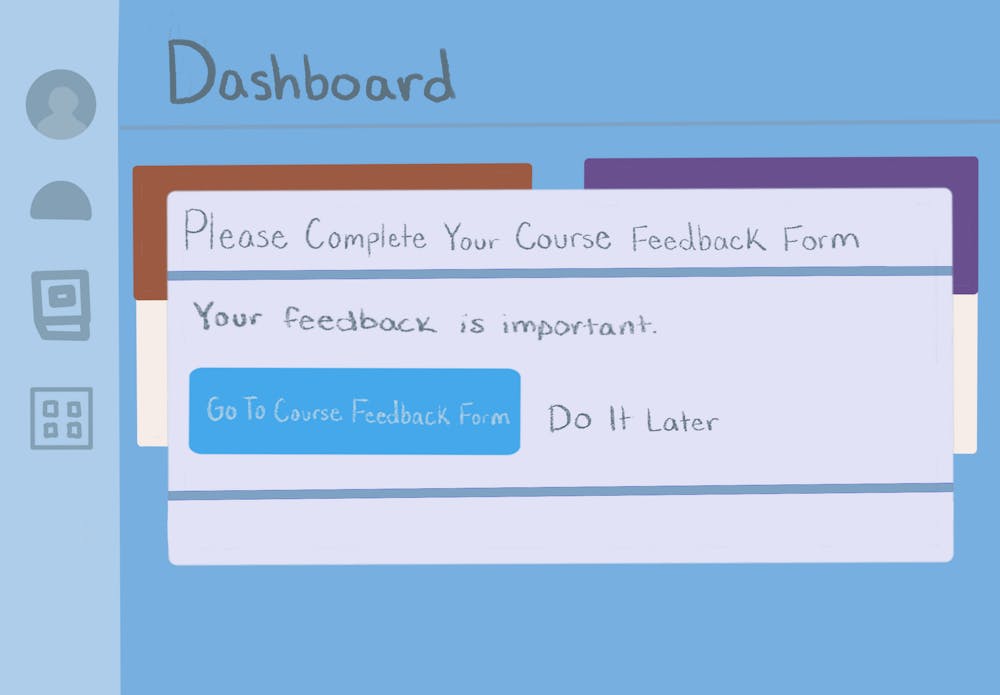

“Please complete your course feedback forms!”

Every Brown student who logs into Canvas during the last few weeks of the semester is familiar with this message. Even though some students may dread seeing the persistent pop-up, course evaluations help professors improve their teaching and course design, several instructors told The Herald.

Course evaluations allow students to provide anonymous feedback on course curriculum and instruction, and the results are reviewed by both the department and the professors themselves. Associate Teaching Professor of Education Katie Rieser MA’17 uses course evaluations to “think through next steps in teaching,” she wrote in an email to The Herald.

“I rely on course evaluations, personally as a professor, to get feedback from my students on … what has worked in the class, assignments, discussion dynamics, feedback on lecturing, reading assignments and so on,” said Tara Nummedal, a professor and chair of the Department of History, in an interview with The Herald.

While course evaluations serve important purposes for all professors, they are particularly significant for instructors in their first few years of teaching, according to Andrew Foster, a professor of economics and former chair of the department.

“When people come in as junior faculty, often in the first few years, they’re trying to learn how to do the job,” Foster said.

The Department of History reviews the work of junior faculty members every year considering both peer evaluations from tenured faculty and course evaluations from students, according to Nummedal.

When John Friedman, current dean of the Watson School of International and Public Affairs, was the chair of the Department of Economics, he found it “often helpful to go through (course evaluations) together” with junior faculty and support them in becoming better teachers.

Feedback from course evaluations also helps Friedman revise his own instruction. “I actually typically do a mid-course evaluation as well that’s not part of the formal system,” he said, explaining that the mid-semester evaluation helps him “get a sense of where students are and adjust as the course is going on.”

Others, like Foster, include student responses from previous years’ course evaluations on their syllabi to help students decide if they should take the course.

“I want the right students to take my class,” Foster said. “I want students to come to the class who understand what I am trying to do, (what) skills I’m trying to teach, the sensibilities and so forth.”

For Robert Ward, an assistant professor of the practice of English who has been teaching at Brown for 16 years, student evaluations also play an important role in planning future courses.

While he hopes for positive comments, Ward said he often analyzes “more constructive” feedback.

“If there’s a few students who are saying the same thing, then I consider whether I can actually act upon that,” Ward said.

But while course evaluation feedback is often valuable, “that does not mean that all the information in course evaluations is always useful,” said Friedman. “Sometimes students say things that are just not that nice.”

“If it’s one student with an objection to something or even a student who’s either extremely positive or extremely negative, sometimes those are outliers,” Nummedal said.

While most faculty believe this feedback is helpful, the University’s July agreement with the Trump administration — which requires Brown to review course evaluations and “identify any reports of antisemitism, which will be promptly referred to (the Office of Equity Compliance and Reporting) for appropriate action” — has raised concerns among some professors.

“There’s a real concern that these course evaluations will be weaponized … now that it’s not just an internal matter of the department or the University,” Nummedal said. “Many of my colleagues have experienced a real chill in the classroom this year.”

According to Nummedal, as a department chair, she is required to read all evaluations in the department, and if she sees “any instances of Title VI violations, specifically antisemitism,” she must report them to the OECR.

Graduate students may also be “especially vulnerable” to these claims, Nummedal added. There are many students “who are here on visas … who feel especially vulnerable to any kinds of charges of, say, antisemitism” that would threaten their immigration status.

Dean of the College and Professor of Slavic Studies Ethan Pollock wrote in an email to The Herald that “Brown’s federal agreement did not change our longstanding approach to course evaluations.”

Quoting a list of frequently answered questions posted by the Division of Campus Life, Pollock wrote that the federal agreement already “aligns with Brown’s existing obligations under the Nondiscrimination and Anti-Harassment Policy and does not reflect any additional government oversight of course material or curriculum.”

Besides providing feedback, course evaluations also serve “as a record of (professors’) teaching and the quality of their teaching” in tenure and promotion proceedings, Nummedal said.

For Ward, who is not tenured, course evaluations are “a vital part of” his contract renewals every three years.

Course evaluations for courses with teaching assistants also ask students to provide feedback regarding their experiences with their TAs.

“If the students have some specific feedback for the TA, then I can talk with (the TA) about it, and they can consider how they might want to respond differently next time,” Nummedal said.

To encourage students to fill out the course evaluations, Nummedal tries to establish a “good rapport” with students. “I hope that at that point in the semester, I’ve established an environment in which I welcome their contribution to the pedagogy of the class,” Nummedal said.

Others, like Rieser and Ward, have allocated class time for students to fill out the course evaluation.

Pollock said that this year, a committee of students and faculty will conduct a review of the course evaluations process and publicly share results from the review. This review happens periodically, with the most recent one taking place in the 2017-18 academic year, according to Pollock.

“This group will focus on evaluating the effectiveness of our feedback process and suggesting improvements,” he said.

Ivy Huang is a university news and science & research editor from New York City Concentrating in English, she has a passion for literature and American history. Outside of writing, she enjoys playing basketball, watching documentaries, and beating her high score on Subway Surfers.